Powerful new imaging techniques reveal humans were already crafting complex hunting weapons from wood 300,000 years ago, upending the stereotype of the Stone Age.

Archeologists have previously suspected humans have been using wooden tools for at least as long as stone ones, but due to wood's more fragile nature, most evidence has rotted away.

Now, using 3D microscopy and micro-CT scanners to examine 187 wooden artifacts from Schöningen in Germany, archeologist Dirk Leder from the Lower Saxony State Office for Cultural Heritage and colleagues have confirmed the suspicions.

"Wood was a crucial raw material for human evolution, but it is only in Schöningen that it has survived from the Paleolithic period in such great quality," explains University of Göttingen archeologist Thomas Terberger.

Amidst this stash of wooden artifacts, the largest known from the Pleistocene (2.58 million to 11,700 years ago) were at least 10 spears, seven throwing sticks, and 35 domestic tools. They were all carved from woods known to be both flexible and hard, including spruce, pine, and larch.

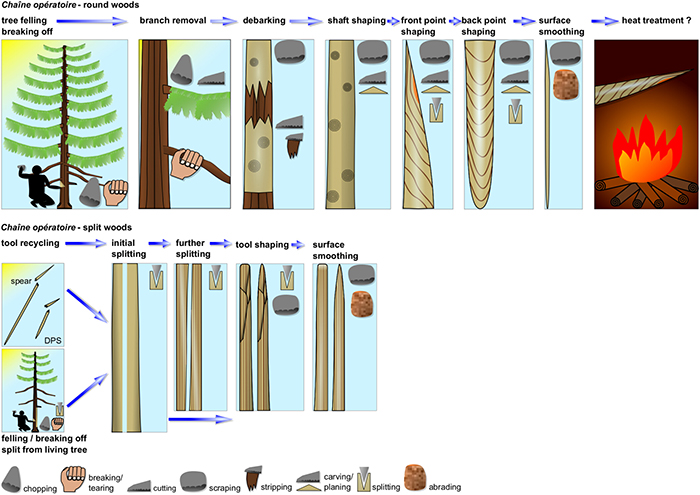

The tools showed clear evidence of a splitting technique previously only known to be used by modern humans, as well as signs of carving, scraping, and abrasion.

"The way the wooden tools were so expertly manufactured was a revelation to us," exclaims University of Reading paleolithic archaeologist Annemieke Milks.

Working wood to the discovered level of sophistication is a slow and many-step process, requiring much patience and forethought. What's more, the age of the tools coincides with when Neanderthals were rising to dominance in Europe, outcompeting other early human species.

The site at Schöningen also contained evidence of up to 25 butchered animals, mostly horses.

"It turned out that these pre-Homo sapiens had fashioned tools and weapons to hunt big game," Terberger told Franz Lidz at the New York Times. "Not only did they communicate together to topple prey, but they were sophisticated enough to organize the butchering and roasting."

These powerful hunting abilities are likely much older than the wood artifacts found in Schöningen, the researchers argue. These skills would have ensured early humans had access to high-quality food sources for generations, providing the capacity for this increase in brain growth and associated cognitive skills.

"Likewise, [hunting] would have ensured sustainable populations even in less favorable parts of Europe during the Pleistocene and contributed to human range expansion across the globe," Leder and team write in their paper.

Incredibly, the researchers also found evidence of recycling. Tools that had been broken or blunted were reworked for new purposes.

"The study provides unique insights into Pleistocene woodworking techniques," the researchers conclude.

"Schöningen's wooden hunting weapons exemplify the interplay of technological complexity, human behavior, and human evolution."

Their study was published in PNAS.