This is an edition of Up for Debate, a newsletter by Conor Friedersdorf. On Wednesdays, he rounds up timely conversations and solicits reader responses to one thought-provoking question. Later, he publishes some thoughtful replies. Sign up for the newsletter here.

Last week I asked, “What should be done about fentanyl? Has it affected your family or community?”

Judy shared a personal tragedy:

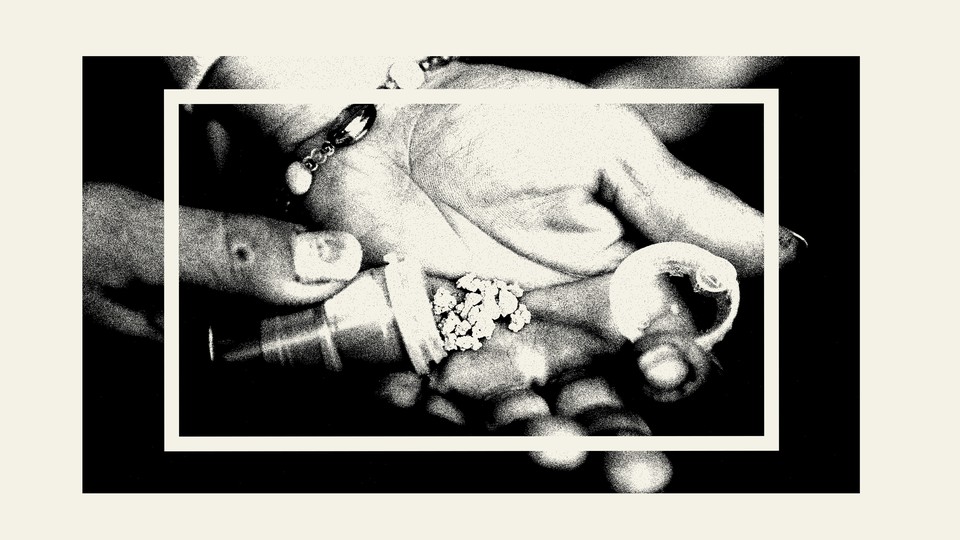

My 26-year-old son died of an overdose of heroin doctored with fentanyl. We would learn two weeks later that he had passed the bar exam in South Carolina and would have become a practicing attorney. I was not aware my son had ever used heroin. He was not an addict but was dating a woman who was purportedly in recovery. I found a text exchange between them on his iPhone in which he sent her a photo of a baggie with the question “What is this?” The baggie had been found on the floor of his truck. Her reply was couched in slang that I cannot decipher, so I’m not certain he knew exactly what he was using. He was the youngest of my three sons. I’ll never know the full details of why he overdosed.

Max is “a recovering addict … and now, an ex-felon, free after three-plus years in federal prison for drug crimes.” He writes:

The market for fentanyl exists for one reason—because it is easier and cheaper to import than heroin, making circumventing interdiction easier. The high is the same.

From experience, I can tell you without doubt that opioid addicts are just looking for the same high they always sought. Users are not seeking out fentanyl because it gets them higher, or because it’s somehow better than other opioids—they’re buying fentanyl because that’s what’s on the street now. And fentanyl is what’s on the street now because it’s easier to get into the country. Fentanyl is stronger, per microgram, than any illicit opioid that has come before—everyone knows this. But the salient point about that fact is that drug producers, smugglers, and dealers can suddenly get as many people high off of one kilo of pure fentanyl as they would have with 10 kilos of heroin. Which means equal profits for a fraction of the shipping cost and risk of arrests, interdiction, etc.

The fact is, people want to get high. There is a portion of the population that is just plain uncomfortable in their own skin—no matter how successful they may appear—and are predisposed to seeking chemical assistance. I just don’t think it’s an issue we can legislate or enforce away. Until we find a cure for the sad human condition, we will have a drug problem. (I’ve been clean six years now—including three inside [prison]—but only because I’ve managed to obtain access to buprenorphine, which is actually just another opioid [prescribed to treat an opioid-use disorder], although a milder, legal one.)

The fentanyl problem exists on the same level as the synthetic marijuana problem: It’s only here because we forced it to be. America’s War on Drugs has imposed a ridiculous, artificial price hike on everything we’ve deemed “illicit” … Think about it: Marijuana doesn’t cost any more to produce than cilantro. Heroin could be as cheap as aspirin. And so on and so on—99 percent of the cost of “drugs” stems from the fact that they’re deemed illegal, and thus every step of production and distribution must be clandestine.

By trying to fix this social ill through prohibition, we’ve simply created an incentive for the market to come up with something that turned out to be worse. The mere existence of the fentanyl problem—like the synthetic cannabinoid problem, the “bath salt” problem, and many others—traces back to our own efforts. The drug war needs to be rethought before something even worse comes along. We have only ourselves to blame.

Read: What does a good health-care system look like?

Claire proposes a policy change:

Fentanyl has flooded the market because of the restricted access to pharmaceutical-grade opioids, and because cartels manufacture it for a tiny fraction of the cost of an equivalent kilo of Afghan heroin, at a much higher potency, with precursors made in China. The clandestine production leads to variability in quality and potency that imperils the consumer. The cartels make billions and may even work with endemically corrupt government(s), such that it isn’t just a matter of sneaking past a border guard; they can facilitate elaborate systems of fraud (like buying or imitating pharmaceutical companies).

I would be in favor of decriminalizing all drugs so that consumption can be regulated for safety, and usage can be guided via education or harm-reduction programs, when necessary. The bureaucracy built around the War on Drugs is incentivized in the opposite direction.

Melanie’s loss of a family member colors how she thinks about her work helping children, which she sees as the key to heading off substance-abuse problems:

My sister-in-law's stepdaughter died from a fatal drug overdose. I always called her my niece. She had been actively addicted to heroin, so fentanyl is considered [a likely factor]. She grew up in a rural area on the New York–Pennsylvania border called “meth valley” 20ish years ago; meth took a huge toll on the area, but it’s not as though the community was thriving before.

On her 13th birthday, her mother gathered her possessions into a garbage bag, drove her to her father’s house, and said, “I can’t handle her anymore.” A few months later, her father went to jail, his girlfriend (my sister-in-law) sent her back to her mother’s house, and her mother placed her in a group foster home. There were a lot of group foster homes in that area and very few services to keep families together.

Parents were keen to protect their children from the ravages of meth by putting them into therapeutic group homes; parents would do this when their kids exhibited typical teenage drug use like drinking or smoking marijuana, or even teen waywardness. But the trauma was immense, and the services of underwhelming value. Staff seemed to think my niece’s decision to use drugs (at that point, marijuana) had more to do with depictions of it on That ’70s Show than the fact that she’d watched her father try to kill her brother and regularly hid with her little half sister when her father went on violent rampages.

When she was transitioning out of the group home, getting ready to live with me first, then eventually her mother, she mentioned that people in her area were switching from meth to heroin. Eventually the rest of the world caught on and other locales caught up.

My niece emerged from the group home very angry, more traumatized, and desperate for love. That’s probably the most potent combination for ensuring that the generational cycle of addiction and trauma continues, and her adulthood was a series of abusive relationships and addictions, interrupted by stays in jail. At times she could overcome her addiction to chemicals, but not to relationships that held the promise of giving her the family she never quite had. When she died, she left three children behind in foster care. I want to believe they can have good lives, but I know the statistics about how terrible foster care is.

What role did the War on Drugs play in all this? It led us to believe that we needed to fight a war on drugs, not a war on child abuse, neglect, maltreatment, and general human misery.

We love narratives that imply that the mere proximity of a drug causes addiction, and that waves of different chemicals (crack, meth, heroin) are discrete events, instead of a continual effort by the most hurt among us to numb their pain. Fentanyl is a little different in that it is so likely to cause overdose fatalities. So it makes addiction harder to hide, both within families and in the media. We’re talking about it more, and we’re talking about its users with greater kindness and compassion. But we need to move the conversation to prevention.

We have known for over 20 years that childhood trauma is strongly linked to substance abuse. We have known for nearly 50 years how to prevent a significant amount of childhood trauma, and we have had plenty of time to invest in more research, if that was ever a priority. It’s my job to prevent childhood trauma through public education and policy. And normally I’m very optimistic about it. But right now, I’m facing the first Christmas without my niece and I’m not optimistic about much.

Claire’s family had a positive experience with fentanyl:

Five years before she died in 2006, my mother came to live with me. In addition to severe scoliosis and emphysema, she already had multiple compression fractures of her spinal vertebrae, and there were to be many more. A couple of years later, following a particularly painful compression fracture, her medical team gave her a fentanyl patch—and the effect was magical. The pain receded and remained bearable even after the patch was removed. No other form of pain relief other than morphine ever gave her as much relief as that one patch. Until I learned of all the fatal overdoses, I have always thought of fentanyl with gratitude for the relief it gave my dear mother. My deepest sympathy and love to all those who have suffered because of this drug.

Marjorie needs powerful opioid pain medication:

I am 44 years old, single, female, and an acupuncturist with my own successful business for 12 years. Before that I was a licensed social worker in New York City. I have an inoperable thoracic syrinx that causes me 24/7 severe nerve pain that requires a combination of nerve medications and opioid pain medications. It became active three years ago so that my torso, chest, and pelvis burn and stab. I go to the Ainsworth Institute for Pain in New York and my primary-care doctor prescribes non-opioid medications. I have undergone several procedures from neurosurgeons at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, including two failed spinal-cord-stimulator trials and a failed pain-pump trial with complications.

I have never felt addicted to these medications. I am dependent on them for physical nerve pain.

It took me about a year, and getting my gallbladder removed, to finally be prescribed opioids regularly. I was bounced around like a hot potato because of the “opioid epidemic.” If I were to go to an ER, staff could label me “drug seeking.” During three ER trips, my blood pressure soared, I cried and was never prescribed pain medications.

I wish I did not have to take these medications. They cause constipation so bad that I have almost gone to the ER multiple times. I now take stool softeners daily and magnesium powder three to four times a week. I have miraculously learned to work in a lot of pain, to cope the best I can. I was switched to 20 milligrams of methadone daily and Percocet as needed, which I try not to take. I take [the neuropathic pain medications] pregabalin and gabapentin. I get blood drawn every three months. My liver enzymes were batty two times because I was taking too much acetaminophen.

I worry about my liver processing so much medication. However, the medication is keeping me alive. The indescribable pain caused me suicidal thoughts for the first time in my life in the first year. Those thoughts are now gone because my pain is controlled “just enough.”

I have become an avid cold-water swimmer with a group on Long Island that has helped me to cope. I belong to a chronic illness/pain group called the Chronicon Community by Nitika Chopra that has been a godsend. We are reading The Invisible Kingdom: Reimagining Chronic Illness by Meghan O’Rourke for our book club. I pray the street-fentanyl crisis is healed. I pray science can someday solve nerve pain and neuropathies.

Marsha blames the Drug Enforcement Administration for the hardships she experiences in getting the pain medication that she needs:

The doctors in the Emory Pain Center made it more and more difficult for me to get oxycodone. Finally, my doctor simply refused to give it to me. He agreed that there was no likelihood that I would become an addict as I have been stable on the same dose since 2007. But he simply did not want to give me the one drug that helps my pain with the fewest side effects. I had been receiving oxycodone from my rheumatologist for about 12 years. She became frightened that her office would be raided by the DEA if she kept prescribing Percocet to patients. She gave me a month to find another doctor to prescribe it.

Has the DEA saved anyone from drug addiction? Or has it simply made life very difficult for people like me?

I see a specialist for pain alone every 28 days. The appointment lasts about 20 minutes from arrival to departure. I am given a paper prescription. I must carry that paper prescription in person with ID to a pharmacy. I must stand in line while it is refilled. I am 79. I have trouble driving. I have trouble standing. I fear catching COVID.

There are only two DEA accomplishments that I am aware of. One is to make pain control more difficult for people like me. The other is to cause many, many deaths. By putting such strict control on prescription drugs, users have been driven to heroin and fentanyl.

What an accomplishment.

Victoria’s daughter died from fentanyl. She is raising that daughter’s four children (ages 14, 14, 10, and 4).

She writes:

You are spot-on about the failure of interdiction to stop the proliferation of fentanyl. Better luck catching a moonbeam in your hand, as the nuns sang in The Sound of Music.

We have to drop the stigma and provide lifesaving treatment, even if that is achieved by providing safe fentanyl. We need to follow in Canada’s footsteps and provide clinics where people can obtain safe heroin and fentanyl, not just clinics where they can use the drugs they procured on the street. Without the stigma, these are eminently reasonable ways to save lives. And it keeps people in the medical orbit until they are ready to seek treatments like buprenorphine or methadone.

Heather agrees:

I lost my 23-year-old cousin to heroin, despite him trying incredibly hard to overcome his addiction. I am a proponent of harm-reduction centers where naloxone is available. I would love to see these centers have options for treatment and counseling at no cost.

Waging a War on Drugs is not going to stop deaths. Allowing people to be seen and heard in a judgment-free safe place is what I think will start to make a difference. There are so many people who are afraid to get the help they need because of the fear of “getting in trouble.” As a previous EMS provider, I cannot tell you how many times we picked up a teenager who (for example) took cocaine and suddenly panicked but who would not admit to it for us to safely and effectively treat them.

Whereas Peter favors a draconian crackdown on the illegal-drug trade. Among the steps that he suggests:

Unless we fundamentally revisit U.S. self-limitations on much stronger actions to both reduce supply and improve treatment, there really aren’t any good answers here, just bad versus less bad.

Singapore has 50 times fewer opioid users per capita and over 35 times fewer opioid deaths per 100,000 people (1.18 vs. 42 ) than British Columbia, Canada, because Singapore has maintained extremely harsh punishments for drugs, like public flogging and the death penalty for drug dealing/smuggling. One could rightly say such punishments are inhumane.

However, given the more than 80,000 annual U.S. opioid deaths [in 2021], and another 500,000 [opioid] addicts inflicting misery on themselves and widely spreading their crime and homelessness through neighborhoods they live in, at this point it’s pretty clear that, from an objective humanitarian and societal perspective, Singapore’s approach is much more successful. It may well be time to consider Singapore-type draconian measures for at least medium- to large-scale trafficking.

… And since interdiction is no longer significantly useful, we’re going to have to go much harder after manufacturing bases and precursor interdiction. It’s relatively well known where manufacturing is being done, and could be much further improved with drone and/or satellite-based chemical-signature area scanning. Because of complete systemic governmental corruption, the U.S. needs to start playing real hardball with Mexico, up to and including suspension of the NAFTA/USMCA treaty, to allow rapid, direct U.S. attacks on cartel manufacturing facilities via drone and/or precursor-transport networks.

Read: Will an influential conservative brain trust stand up to Trump?

Jaleelah does not believe fentanyl can be eliminated. She explains why before offering an alternative approach to the problem:

In Canada, large cartels aren’t the main importer, and domestic producers contribute to the trade. Fentanyl use is often accidental—less potent drugs are often laced with fentanyl—so public-service announcements discouraging use won’t stop the deaths. It’s hard for authorities to detect it in the mail, and it’s hard for run-of-the-mill drug users to detect it in their supply. Given these facts, the focus should be mitigating the harms of fentanyl rather than stopping it in its tracks.

If the government cares about stopping fentanyl overdoses, it must implement testing programs for other drugs. Users of cocaine, heroin, and meth should be encouraged to bring their supply to government facilities where they can figure out if their drugs are laced. The government must assure users that they will not be arrested or tracked for the crime of being safe. Facilities like this already exist in parts of Canada.

Government intervention alone will not stop the death. Uptake will be slow, and some people will still use fentanyl intentionally. Additionally, many people can’t call for help by themselves when they’re suffering the effects of fentanyl. We need strong social norms in favor of helping our fellow citizens when they are actively overdosing.

People are afraid of drug users. I have seen an overdose once in my life. I was 18, and I regrettably did not rush to help. I was in a parked car in a dark, nearly empty garage and I was initially paralyzed by the fear that the man screaming and coughing up his lungs would lash out if I offered assistance. Thankfully, two passers-by jumped into action: One ran to grab a naloxone kit, and one sat with the man and comforted him until an ambulance arrived.

Lots of people see drug users as irresponsible, selfish people who refuse to get their lives in order. The reality is that rehab programs—if they’re even affordable—are ineffective. To reduce use of common fentanyl vectors like heroin, cocaine, and meth, we need to invest in scientific and sociological research to produce recovery programs that aren’t based on religious moralizing.

Opioid addiction has a genetic component, meaning that many addicts aren’t morally responsible for lifetime addictions (beyond the responsibility they bear for making one or two bad decisions—or succumbing to peer pressure—as a teen or young adult). We need to stop viewing addiction as a moral failing and start realizing that it’s a failure of the health-care system.