A Manual for Surviving History

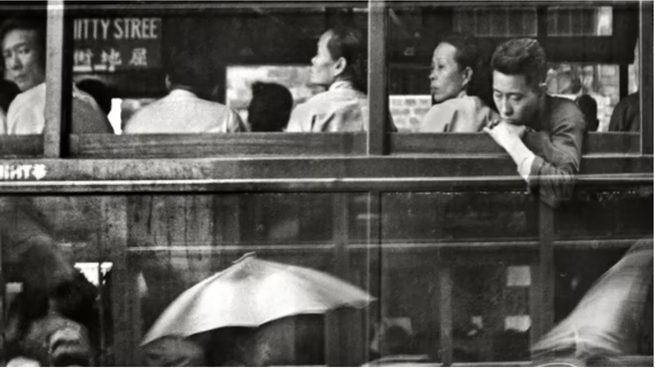

For the Shanghai-born writer Eileen Chang, observation was a way of life.

This is an edition of the revamped Books Briefing, our editors’ weekly guide to the best in books. Sign up for it here.

Anyone who could use a guide to get through our unstable, terrifying era should look no further than the work of Eileen Chang. The Shanghainese writer, whose artistry Meng Jin explores in an essay for us this week, wrote intimately about daily life during chaotic times. While she was alive, Chang was widely read in Hong Kong and Taiwan, though her novels were banned in mainland China for decades. Recently, she has experienced a surge in popularity among Chinese women—and her work warrants close attention from any reader drawn to an ethos of everyday wisdom.

First, here are three new stories from The Atlantic’s Books section:

Reading Jin’s reflections on the essay collection Written on Water, I realized why Chang has enthralled so many contemporary women. Like us, she lived through a turbulent period: Japan’s occupation of Shanghai, World War II, the Chinese civil war. But she was resolutely focused not on battle, politics, or the decisions of powerful men, but on smaller preoccupations—gossip, romance, “irrelevant trivialities,” as Chang once referred to them. That doesn’t mean she ignored the political upheaval happening around her. As Jin notes, the “historical noise flickers in the background of Chang’s writing—and, if you look closely, informs its very core.” But she understood that we can’t really know people when they’re blustering on the world’s stage; the truth is visible only when we observe them with their guard down.

Observation was a way of life for Chang, even, as Jin puts it, something of an “ethic.” For example, I relished Jin’s discussion of Chang’s philosophy on clothing. Loving clothes, like loving gossip, is frequently denigrated as too female, or dangerously frivolous. But Jin points out just how misguided that is: The things we wear are a “container for life itself.” As Chang wrote, “If men were more interested in clothing, perhaps they would become … a bit less inclined to use various schemes and stratagems to attract the attention and admiration of society and sacrifice the well-being of the nation and the people in the process of securing their own prestige.” Her work’s focus on the little things ironically brings her audience a sense of solace, by providing not only a guide to living one’s life in the face of Earth-shattering events, but also something like permission to do so.

The Juicy Secrets of Everyday Life

What to Read

Since the vaudeville era and the early days of Hollywood, ethnic minorities have defined American comedy on stage and screen, but the publishing industry seems to prefer that writers of color present themselves as the subjects of grim generational trauma. In Erasure, Everett goes straight at this limiting convention with a bitterness so evident that the reader cannot help but laugh. The English-professor protagonist, enraged by the success of his peer Juanita Mae Jenkins’s novel We’s Lives in Da Ghetto and goaded by his agent’s complaint that his own writing is not “Black” enough, writes a book whose working title is My Pafology. He eventually changes it to Fuck. The full text of this fictional novel appears within the book, giving us both Everett’s parody of Black literature that panders to white audiences and his idea of what would happen if that parody were unleashed upon the world. — Dan Brooks

From our list: Nine books that will actually make you laugh

Out Next Week

📚 A Terribly Serious Adventure, by Nikhil Krishnan

Your Weekend Read

Philosophy Could Have Been a Lot More Fun

If Diogenes asked how one can live with integrity in an unjust world, the answer we have is not in what he wrote but in what he did. Instead of musing on the metaphysics of justice within the walls of an academy complicit in wealth and power, Diogenes exposed injustice and its obfuscation, demonstrating by example that what seems natural or inevitable is not. Life can be examined not just in theory but in practice: through trials of life that widen our conception of what is possible or desirable—as Diogenes did.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.