America Gave Up on the Best Home Technology There Is

The death of the landline was premature.

This article was featured in One Story to Read Today, a newsletter in which our editors recommend a single must-read from The Atlantic, Monday through Friday. Sign up for it here.

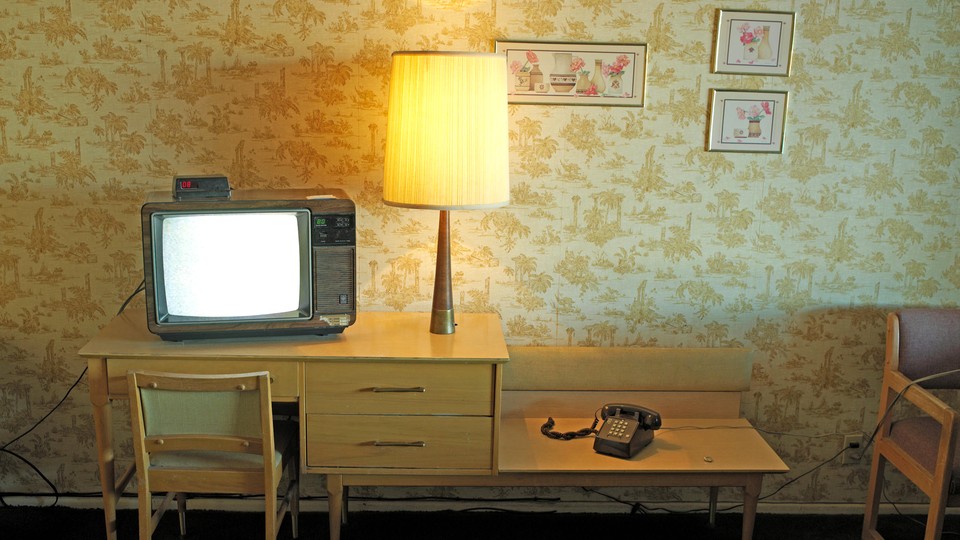

Until last month, I hadn’t kept a landline phone at home since 2004. I deemed it so useless that for a while I even used the digital phone service that came with my cable subscription as a fax line instead. I did eventually hook up a home telephone in 2013, but only briefly, on a lark: It was a Western Electric 500 that I’d bought for my daughter at a vintage shop. The device was just a curiosity, and a way to re-create the lost catharsis of “hanging up” a call. Even then, the home telephone was long dead.

According to the CDC’s National Health Interview Survey, which has been tracking American telephone use since 2003, fewer than 30 percent of American adults lived in a home with a landline phone last year. Those who still have one may have set it up ages ago—more than half of Americans over the age of 65 rely on landlines, and fewer than 2 percent of Americans use them as their only telephone. None of this is surprising. Once you have a cellphone in your pocket or your purse, you don’t need to keep a separate phone at home. Right?

Wrong. Landlines are amazing, and we were wrong to disavow them. I resumed my landline service this summer and quickly found a benefit that my rectangle can never match: My landline is a phone for my entire home, instead of being for a single person who happens to be housed within it.

When we installed our new landline, we did have someone in particular in mind: my 9-year-old daughter. She does not have a cellphone. She does have an iPad, but mercifully she isn’t glued to it at all times. Occasionally we want to reach her from afar—or her older brother or sister does (they live in another city). Any of us can text another adult to go find her, but this is burdensome, and it robs my 9-year-old of what little autonomy she has: She must be summoned through channels rather than acting in the world directly.

We also worried how our little one might reach out for help in case of an emergency. I still remember learning, when I was in kindergarten, how to dial 911. But what’s my daughter going to do? Search countertops or pockets for a phone, and then try to remember the passcode for the lock screen? Even for a lesser need, she wouldn’t have a way to call a neighbor or a relative. It used to be that any risk of kids’ being incommunicado in the home could be easily averted—just teach them how to use the family phone. Now we simply accept a slight unease that lasts until they have a smartphone of their very own.

Pondering all this made me realize what was lost when landlines were abandoned. Phones used to belong to a household; now they’re personal property. A shared line was irritating when it was the only option: Teenagers (or modem-connected computers) might tie up the phone for ages, a few handsets scattered throughout the house limited privacy on the phone, and anyone could fill your home with telephone bells at any time, day or night. But in exchange, your house got a common line in and out. In a small but important way, it emphasized the household as a unit, one with common interests, a hub through which contact with its members could be made.

The house phone facilitated common projects. Everyone might have to talk to Grandma, depending on who picked up. But also, whoever was home could, and might be obliged to, interact with the plumber or the super or the lawn-chemical guy. When phones became personal, those duties got assigned to individuals; handing them off required new forms of coordination. “Just a heads-up,” I now text my wife at home, from elsewhere, “the lawn-chemical guy is going to show up later.”

If a citizen of the present finds it disturbing that anyone else can make their phone ring or buzz at any time, it’s because that phone is now with them at all times, including at moments incompatible with interruption. We lament that smartphones have allowed us to bring our work into the home, but the same devices have also allowed us to bring our home into the workplace, and into every other place we go. Now you must deal with the plumber from the office, or the train, or the Starbucks toilet, or the podiatrist’s waiting room. No wonder a phone call so often feels unwelcome.

Interruption was once a feature of home phones, not a bug. Absent other means, people wanted there to be a way of contacting them directly. Landlines sounded better, too. But I’ve found that our new home phone improves the call experience in other, more surprising ways. Before we put it in, we’d often find ourselves grouped around a cellphone lying on a table so we could FaceTime as a family. We wouldn’t care about the video and let the camera send an image of our ceiling. What we really needed was an effective, hands-free speakerphone—and that’s exactly what the desk-style phone in my kitchen now provides. Cordless phones once promised to let callers move around, but mobile phones perfected that act. Now telephones can reclaim a previous limitation—immobility—as a benefit: If a landline is a phone for a house, then a landline handset can be a phone for a room within that house.

I’m using the word landline vestigially: New home phone service is almost never delivered via analog, copper-wire telephone line; instead it’s digital, piggybacking on a cable or internet service line. And just as a mobile phone can do much more than make telephone calls, so landline phones have changed too. In my case, I installed what amounts to a small-business telephony system in my house. I can have as many independent phone lines as I want for $1 or so each per month. I can turn them off if they start to get spammed. And I can now call between the phone handsets in my house, as if I were ringing different extensions at an office. This solves one problem common to life in sprawling American homes—namely, how do you contact people in faraway rooms or on separate floors? Group text doesn’t work, even when your kids do have phones, because they may not be looking at their rectangles at every minute of the day. A modern landline can be an intercom too.

It’s a small novelty, but one that suggests that other, bigger ones are possible. Our homes are riddled with little computers, in doorbells and light switches, inside televisions, and operating sprinklers. Yet this wave of innovation has for the most part passed right over home telephony. Let’s hope for a reversal. A new breed of landline phones, with screens like tablets, might allow a house to share not just a digital hub for smart-home controls, but also information such as calendars, reminders, chores, messages, and notifications intended for everyone rather than one person in particular. All those scraps of paper pinned to cork, and all that ink smeared on dry-erase boards, would at last be obsolete.

Even in its current state, our new landline has been useful. I’ve now reconnected a dedicated line to the old fax machine, because why not, you never know. I’m just one person, and for now a weird one; landlines aren’t quite back, baby. But what if they were? It once seemed impossible that everyone would have a cellphone, let alone carry it everywhere all the time. Maybe they’ll yet again have a phone they always leave behind.