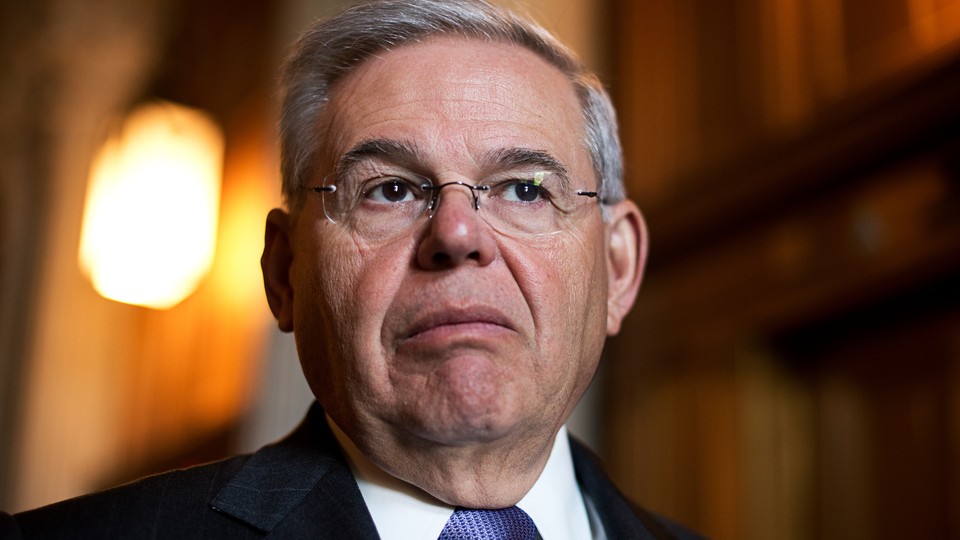

Bob Menendez Never Should Have Been Senator This Long in the First Place

But heated partisanship can keep bad politicians in office, for fear of helping the other party.

In a court of law, defendants are entitled to a presumption of innocence. In the court of public opinion, Senator Bob Menendez enjoys no such indulgence.

The Democrat from New Jersey was indicted today—along with his wife, Nadine, and three others—on three counts of corruption. Federal prosecutors say the group accepted hundreds of thousands of dollars of bribes to assist the Egyptian government. Among other allegations, they say Menendez gave sensitive U.S.-government information to the Egyptians and tried to shield two of the defendants from prosecution.

This isn’t the first federal corruption case against Menendez, and his continued representation of his state in the Senate and as head of the powerful Foreign Relations Committee (at least up until today: Menendez stepped down from the chairmanship after his indictment) are a testament to the pusillanimity of Democrats. The news also shows how the heated partisanship of the current era can keep bad politicians in office for fear of helping the other party.

The indictment includes claims that New York accurately characterizes as “cartoonish.” In Menendez’s closet, FBI agents found envelopes full of cash in the pockets of jackets that had Menendez’s name sewn on them. They also turned up more than $100,000 worth of gold bars, like in some sort of harebrained Yosemite Sam scheme. (For good measure, the bars are stamped Swiss Bank Corporation.) Prosecutors also cite texts from Nadine to Bob Menendez complaining that a co-defendant, Wael Hana, had not paid the bribes he’d promised. And prosecutors allege the senator agreed to derail a prosecution in exchange for a Mercedes C-300 convertible. The document is, perhaps needless to say, a compelling read.

If corruption allegations against Bob Menendez sound familiar, that’s not just because you’re familiar with the recent history of other Democratic senators from New Jersey. In 2015, Menendez was indicted by federal prosecutors for a sweeping bribery scheme, alongside a doctor named Salomon Melgen.

The evidence against Menendez seemed compelling, but he got a lucky break: In the midst of his trial, the U.S. Supreme Court threw out a corruption conviction of former Virginia Governor Bob McDonnell, a Republican, a decision that, Matt Ford wrote, “fundamentally changed the standard for bribery.” The jury hung, the Justice Department dismissed charges, and Menendez got off with a severe admonition from the Senate Ethics Committee. (Melgen was later convicted and sentenced to 17 years in prison for Medicare fraud. Donald Trump commuted his sentence in one of his last acts as president, crediting Melgen’s “generosity in treating all patients especially those unable to pay or unable to afford health-care insurance”—on your dime.)

By then, as the journalist Dick Polman wrote in The Atlantic, Menendez had “escaped more scrapes than Houdini,” and his name was “synonymous with ethical lapses.” The moment would have seemed right for Democrats to be rid of Menendez. Not only was he an ethical liability in his own right, but his presence also undercut the corruption accusations the party was lodging against Trump. But they didn’t want to expel him from the Senate, because New Jersey’s governor at the time, Chris Christie, is a Republican, and could have appointed a Republican to the seat. So Menendez stayed, and in 2018 was reelected to the Senate.

Some people might lay low for a while after a fortuitous escape from the law, but prosecutors say Menendez promptly went back to doing corruption in spring 2018, around the time of his censure. The scheme was helped by the fact that in February 2018, just after charges were dropped, Menendez became the top Democrat on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Three years later, when Democrats retook the Senate, he became the chair. That gave him a perfect position to use his power to benefit Egypt.

Menendez says he’s innocent, and released a scorching statement this morning. “For years, forces behind the scenes have repeatedly attempted to silence my voice and dig my political grave,” he said. “Since this investigation was leaked nearly a year ago, there has been an active smear campaign of anonymous sources and innuendos to create an air of impropriety where none exists. The excesses of these prosecutors is apparent.”

He added: “Those behind this campaign ... see me as an obstacle in the way of their broader political goals.” That sounds a lot like Trump’s “I’m being indicted for you,” and his claims that he’s the target of retribution by the “deep state.” Menendez’s protests are hard to take seriously given that New Jersey is run by Democrats and the president is a Democrat (though Menendez is not a close pal of Biden’s), but voicing these arguments could help validate Trump’s defense against his own indictments, just as Menendez’s presence undermined the political case against Trump in 2018. But Democrats may have only delayed their headache, because Menendez is up for reelection in 2024. His travails could give Republicans a chance at taking his seat.

Menendez’s survival has left New Jerseyans, and Americans, with an ethically compromised senator, because Democrats were afraid that getting rid of him would produce a Republican senator—something they viewed as even worse. Today’s politics is suffused with what political scientists call negative partisanship—the phenomenon where partisans are more motivated by fear and loathing of the other party than affection or affinity for their own. In this way, Menendez’s indictment echoes the 2024 presidential election too, in which each party is poised to nominate a candidate based on the belief that he’s the one best positioned to defeat the other side—not for his own talents or character. Are there worse things than losing an election? The Menendez prosecution might offer one answer to that question.