Dear Therapist: My Daughter’s ‘Brother’ Is Actually Her Father

After 30 years, I want to tell her the truth, but I don’t know how.

Don't want to miss a single column? Sign up to get “Dear Therapist” in your inbox.

Dear Therapist,

When I married my husband, he had two adult children, and I had none. We both wanted to have a child together, but my husband had a vasectomy after his second child was born—too long ago to get the procedure reversed.

We didn’t want to use a sperm bank, so we asked my husband’s son to be the donor. We felt that was the best decision: Our child would have my husband’s genes, and we knew my stepson’s health, personality, and intelligence. He agreed to help.

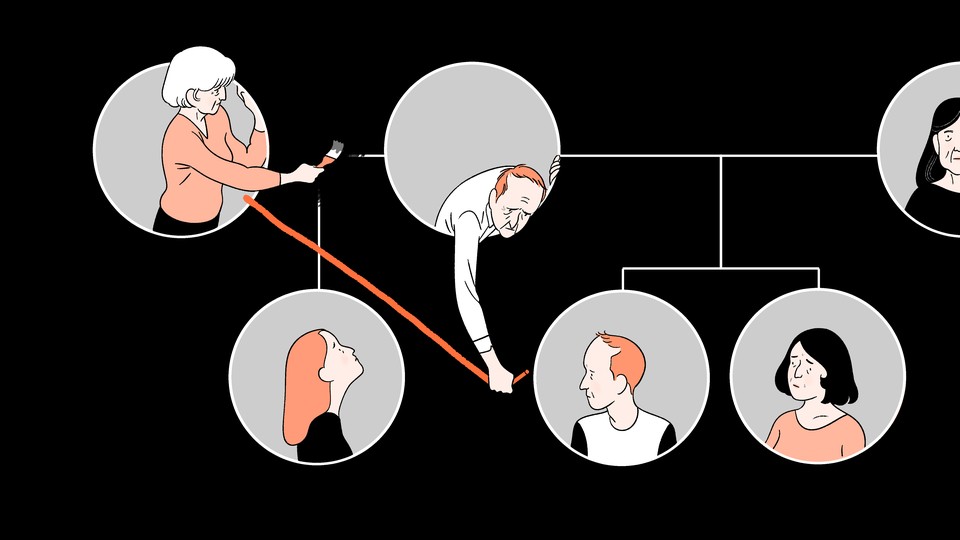

Our daughter is 30 now. How do we tell her that her “father” is her grandfather, her “brother” is her father, her “sister” is her aunt, and her “nephew” is her half-brother?

My husband and I are anxious, confused, and worried about telling her. This is also hard on my husband, because he wants our daughter to know that he will always and forever be her father.

Thank you for any advice you have to offer.

Anonymous

Dear Anonymous,

I’m glad that you and your husband have decided to tell your daughter the truth. As you think about how to have an honest conversation, keep in mind that there are two truths your daughter will be absorbing simultaneously: First, the person she calls her brother is her biological father, and second, the people she calls her parents have deceived her for 30 years.

I point out the latter not to place blame but to prepare you for how your daughter might feel, even if you believe you had good reasons to hide the truth. In fact, I’m certain that you and your husband kept your daughter’s paternity a secret because you felt this would protect her—from confusion, shame, or societal judgment. It’s also possible that you were (consciously or subconsciously) trying to protect your husband, too, from a fear voiced in your letter—that if your daughter knew the truth, she might not think of your husband as her father in quite the same way as she does now.

I have deep compassion for the position you’re both in. At the time your daughter was conceived, 30 years ago, many parents who used a sperm donor were strongly advised by physicians not to share this information with the child, based on the belief that secrecy was better for everyone involved. However, in the years since, many children conceived in this way have said that instead of protecting them, secrecy left them feeling unmoored, angry, and betrayed.

Carl Jung called secrets “psychic poison,” and in fact, secrets can literally make us sick. This applies to everyone in the family—you and your husband, who have held the secret inside; your stepson, who likely has feelings about his biological daughter being treated as his sister, and who might be perpetuating the lie with his own partner and child; your stepdaughter, who either feels the burden of carrying this secret or was also kept in the dark; and, of course, your daughter, who might sense, somewhere deep inside, that something she can’t name has always felt off.

Family secrets have a way of being felt even if they’re unspoken: Many people who grew up in a home with family secrets say that they always had a sense that something was not as it seemed, and that this resulted in chronic unease. What people don’t realize is that in trying to protect a child from whatever danger they believe the truth would pose, they’re likely making that child feel less safe than they would if they knew the truth.

You don’t say why you’ve decided that now is the time to be honest—maybe you realized that your daughter might someday take a DNA test “for fun” and you’d prefer that she find out from you instead of a lab report; maybe you feel she should have access to an accurate medical history; maybe you’ve simply come to see how important it is for her to know the truth about who she is, and for the entire family to live authentically at last. Whatever the reason, and however challenging this revelation might be, know that you’re doing the right thing.

With this context in mind, how do you tell your daughter? First, state the facts as simply and clearly as possible: We have something important to tell you, and we wish we had told you sooner. When we wanted to have a child together, we discovered that wouldn’t be possible. We considered our options and decided to ask your brother to be our donor, because we felt it would be safer and more desirable to choose someone we knew who shared your father’s DNA.

Then apologize and take full responsibility for not telling her the truth from the beginning. Don’t make excuses or ask for her understanding; tell her you can imagine how shocking this must be, and that you feel terrible for denying her the right to know where she comes from and who she is. If she asks why you kept this a secret, tell her what you were afraid of without in any way defending or justifying your decision. Reiterate that if you could do this again, you would be honest from the start. Tell your daughter who else knows, so there are no secrets remaining in the family. Make sure to communicate that you’re aware that you betrayed her trust, and that it might take some time to rebuild. Tell her that this should never have been a secret, and that, because this is her story, you encourage her to share it with whomever she wants.

The key is to talk as little as possible and not make this about your feelings. Instead, check in with her about how she’s feeling, and ask what you can do to support her. She might feel anger, grief, betrayal, relief, or a combination of these—so it will take her some time to process the news. This is simply the first step in what will be an ongoing conversation, so be sure to let her know you’re happy to talk more anytime. If she doesn’t bring it up again, you can gently check in with her every once in a while. And if you or your husband are uncomfortable discussing it once the secret is out, seek counseling on your own so that your discomfort doesn’t make your daughter hesitant to talk openly and honestly with you both.

You should also tell your stepson and any other family members who know the truth that you’re sharing it with your daughter, and that they should be respectful of how she wants to handle her story. Ask your daughter if she wants your support in talking with the person she knows as her brother, or if she would like to seek individual or family therapy (in any combination) to help integrate this new information into her sense of self and navigate the complicated family dynamics. Meanwhile, show interest in and compassion for the feelings your stepson might not have felt free to express when his true relationship with his “sister” was shrouded in secrecy. Remember that even though he was an adult when you asked him to be your donor, he still may not have fully appreciated the implications of being the biological father of someone he would call his sister—someone he’d be forced to lie to.

As you free your family from its long-held secret, you might feel less anxious approaching your daughter if you remember that there will be many conversations to follow, so no single conversation has to go perfectly—and that the truth, no matter how messy, is what makes people feel safe and connected. You clearly love your daughter, and we owe honesty to the people we love.

Dear Therapist is for informational purposes only, does not constitute medical advice, and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician, mental-health professional, or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. By submitting a letter, you are agreeing to let The Atlantic use it—in part or in full—and we may edit it for length and/or clarity.