Detective Fiction Has Nothing on This Victorian-Science Murder Mystery

William Saville-Kent was a pioneering coral photographer. Was he also hiding a grisly secret?

In the summer of 1893, an unusual volume appeared on the shelves of London booksellers. The Great Barrier Reef of Australia: Its Products and Potentialities, published by W. H. Allen and Company, was remarkable both for its price—the leather-bound volume would have cost a skilled tradesperson nearly two weeks’ pay—and for its fantastically close observation of the world’s largest reef system.

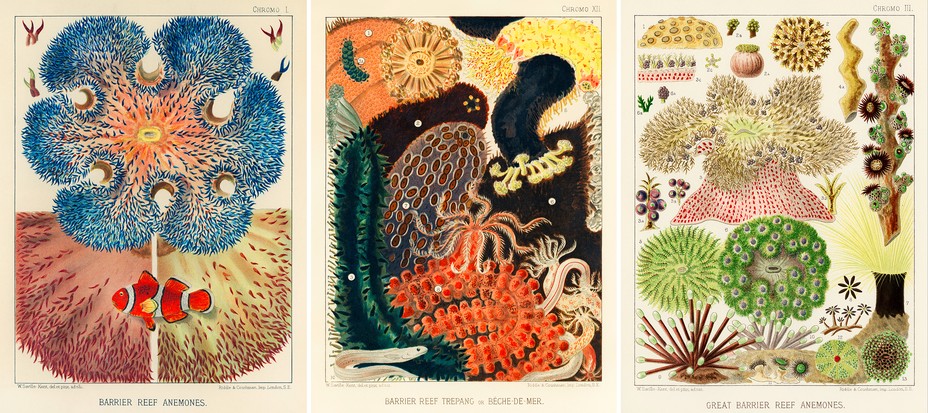

Many British readers knew of the existence of coral reefs, from the accounts of Charles Darwin and other naturalist-explorers. They might have known that James Cook and his crew had been trapped and nearly died in the labyrinthine “shoals” off the eastern coast of what would become Britain’s most distant colonies. But far fewer grasped that coral reefs were living systems composed of countless tiny, soft-bodied animals; even fewer had any real sense of the squirming, kaleidoscopic grandeur of the Great Barrier Reef. For most of its readers, The Great Barrier Reef of Australia revealed an almost completely unknown world.

At a time when photography was cumbersome and expensive and color photography was little more than a curiosity, the author William Saville-Kent had waded into the Pacific at low tide and, with the help of a specially constructed four-legged stand, had worked out a method of photographing coral colonies from above. The resulting large-format prints were exceptionally clear, and Saville-Kent’s accompanying watercolor sketches suggested the polychromatic glory of a flourishing reef: Pale-violet stony corals, orange sea stars, and crowds of colorful reef fish burst from the pages in preindustrial abundance.

To some of the readers who admired Saville-Kent’s work in 1893, his name might have sounded familiar. He wasn’t a famous naturalist. Was he famous for something else? No matter; although the author had recently returned home to England for a frenzied, year-long bout of specimen identification and writing, he had since sailed back to Australia.

Thirty-three years before the publication of The Great Barrier Reef of Australia, the mutilated body of a young boy named Saville Kent was discovered on the grounds of an English country house. Three-year-old Saville lived with his family in the village of Rode (then Road), about a hundred miles west of London, and had gone missing from his bedroom in the predawn hours of June 30, 1860. After several hours of frantic searching by his parents, his four older siblings, the household staff, and several neighbors, Saville’s body was found hidden in the servants’ outhouse. His throat had been cut so deeply that his neck was nearly severed. When the local police arrived and searched the tank below the outhouse, they discovered a “bosom flannel”—a cloth worn inside the front of a corset—that had been recently stained with blood.

The contrast between the grisly crime and its genteel setting shocked the country, and the resulting fear and outrage were soon followed by frustration with the local police. On July 10, an editorial in the national Morning Post called for an experienced detective to take over the investigation, arguing that “the security of families” depended on the killer’s being brought to justice. Within a week, the commissioner of London’s Metropolitan Police had dispatched Detective Inspector Jack Whicher to Rode.

Whicher, then 45, was a member of the Metropolitan Police’s small detective division, created 18 years earlier to investigate serious crimes that crossed precinct lines. The police force itself was not much older, and the detective division, whose plainclothes officers often worked undercover, was widely seen as an unwelcome escalation of state surveillance.

At the same time, the detectives and their rumored powers of observation fired the public imagination. The author Kate Summerscale, in her 2008 book about the murder of Saville Kent, writes that by 1860, Whicher and his colleagues “had become figures of mystery and glamour, the surreptitious, all-seeing little gods of London.” Charles Dickens praised their uncanny abilities, and he described one of his fictional characters, based on Whicher, as having “a reserved and thoughtful air, as if he were engaged in deep arithmetical calculations.” When Whicher arrived in Rode, he was generally expected to not only unmask the killer of Saville Kent but also repair the violated sanctity of the English home.

At first, Whicher’s investigation revealed only the unhappiness in one particular English home, which was occupied by Saville’s father, Samuel; his four children from his first marriage; his second wife; and their three—now two—younger children. Samuel, who worked for the government as a factory inspector, had moved the family to Rode five years earlier, and had quickly made himself unpopular in the village by forbidding fishing in the river near his house. His first wife, Mary Ann, had died in 1852 after enduring years of mental and physical illness and the deaths of several children in infancy. Her symptoms—and those of her surviving children—have led historians to theorize that Samuel had infected her with syphilis, and that she suffered from an advanced form of the disease. Fifteen months after Mary Ann’s death, Samuel married the family governess, Mary Pratt.

The second Mrs. Kent was said to be impatient with her two younger stepchildren, Constance and William, and in July 1856, when they were 12 and 11, the pair had run away from home. In the same outhouse where Saville’s body was discovered, Constance had changed into a set of William’s clothes, cut off her hair, and stuffed her dress and petticoats into the tank. The two had set out on foot for the coast, planning to sign on to a ship’s crew as cabin boys; they traveled about 10 miles before an innkeeper, suspecting they were runaways, reported them to the police. While press accounts of the incident varied, most of them cast Constance as the instigator. Decades later, Constance herself recalled that she had remained defiant when apprehended, leading her questioners to treat her “as a bad boy who had led the other astray.”

While the suspicions of the local police had focused on Saville’s nursemaid, Elizabeth Gough, Whicher was more interested in Constance. Interviews with her schoolmates and the household staff convinced him that the 16-year-old had been consumed with jealousy toward her father’s new family, and toward her young half-brother in particular. He also learned that one of the three nightdresses she owned was unaccounted for, and while she claimed it had been lost in the wash, he suspected she had been wearing it on the night of the murder and had later hidden or destroyed it. On July 20, Whicher arrested Constance, charging her with Saville’s murder.

The detective’s careful observations, however, were not enough to make his charge stick—or extract a confession from his suspect. Constance insisted on her innocence, and after days of searching at Whicher’s behest, the missing nightgown remained missing. After a week in jail, Constance was examined before a sympathetic audience by the local magistrates, who apparently agreed with her lawyer’s claim that “there is not one tittle of evidence against this young lady.” Constance was released on July 27, with the stipulation that she remain available for further questioning. The next day, a defeated Whicher took the train back to London.

The press condemned the detective for his failure, but he continued to believe that Constance had killed Saville, perhaps with the knowledge or assistance of her brother William. He was further convinced of his theory in November, when it emerged that immediately after the murder, a local police officer had found a bloodied woman’s gown shoved into the kitchen stove. “After all that has been said in reference to this case,” Whicher wrote to a colleague, “there is in my humble judgement but one solution to it.”

Few believed him, and the reputation of Whicher’s profession suffered along with his own. In the aftermath of the Rode case, detectives were no longer “all-seeing little gods” but all-too-fallible mortals. As Summerscale notes, the word clueless came into use in 1862, and in 1863, the satirical magazine Punch skewered “Inspector Watcher” of the “Defective Police.” The following year, Whicher took an early retirement at age 49, citing “congestion of the brain.”

On April 25, 1865, 21-year-old Constance Kent confessed to killing Saville.

In the years since the murder of Saville Kent, most of the Kent household had moved to north Wales. Constance had spent two years at a finishing school in France, and in the summer of 1863 had returned to England, boarding at an Anglican religious home in Brighton run by Reverend Arthur Wagner. Wagner was a controversial figure, known for his support of Roman Catholic practices such as private confession, and it was during an interview with Wagner that Constance first unburdened herself.

In her formal confession, submitted to a London magistrates’ court, Constance stated that she had killed Saville “alone and unaided,” and that no one had known of her actions. Shortly afterward, she wrote that she had experienced only “the greatest kindness” from both her father and her stepmother, and had killed Saville not out of jealousy but in revenge for what she described as her stepmother’s cruel treatment of her mother during her mother’s years of illness. “She had robbed my mother of the affection which was her due,” Constance wrote, “so I would rob her of what she most loved.”

The confession divided public opinion: While some took Constance’s words at face value, others believed she had been manipulated by Wagner, or was protecting the real culprit. Constance maintained her guilt, however, and on July 21, 1865, after a 20-minute trial, she was convicted and sentenced to death—a fate later commuted to 20 years in prison.

During Constance’s first year of incarceration, her brother William turned 21 and moved to London with his two eldest sisters. With the help of his mother’s family, he began taking evening classes, apparently preparing for a career in the civil service. William was far more interested in flowers and insects than bureaucracy, however, and whenever he could he attended the public lectures offered by the era’s leading naturalists.

During the years that the Kent family was undergoing its private and public horrors, the scientific world had been upended. Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection, described in his 1859 book, On the Origin of Species, had challenged the long-standing assumptions that species were static entities and that the human species was set apart, superior to all the others. (Late in life, Constance would recall that she read the book shortly after its publication and shocked her family by endorsing its theory.)

When William arrived in London, Darwin’s work was still enormously controversial, but it had benefited from influential champions such as the zoologist T. H. Huxley, remembered as “Darwin’s bulldog” for his fierce defense of evolution. Huxley was known for his compelling lectures, and William later wrote that they were “the starting point” for his own life in science. For William, science might have also represented a chance to break with his past, for around this time he began to use the hyphenated surname Saville-Kent. Saville, which was his own middle name as well as the name of his late half-brother, was also the family name of his paternal grandmother; he used it for the rest of his life.

Despite the immense public interest in natural history at the time, the study of other species was not yet an established profession, and its practitioners tended to be independently wealthy. Huxley, the son of a schoolteacher, had hammered together a career with his wits and forceful charm, and most of his protégés, including Saville-Kent, were expected to do the same.

Saville-Kent soon developed an interest in microscopy—the ability to study previously invisible life forms was, he recalled, like exploring “a new world”—and with Huxley’s encouragement he began to investigate aquatic invertebrates. As a museum assistant at the Royal College of Surgeons, Saville-Kent became “smitten” with the corals whose calcium-carbonate skeletons he studied. Later, as an assistant at the British Museum, he sailed to Portugal to investigate the glass rope sponge, a species whose clear tissues so puzzled naturalists that some believed it was actually made of glass.

But as Saville-Kent’s biographer, Anthony J. Harrison, recounts, museum work paid poorly, and the young scientist was not only newly married but, after his father’s death in 1872, at least partly responsible for his four surviving half-siblings. Over the next several years, Saville-Kent held a succession of research positions at commercial aquariums, which were newly popular as entertainment (thanks in part to Jules Verne’s novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea). In Manchester, he studied the life cycle of lobsters and developed a method of keeping large species of seaweed alive in captivity; in Brighton, he clashed with a colleague over credit for a study of octopus sex.

What Saville-Kent did not do during these years, apparently, was communicate regularly with Constance. The historian Noeline Kyle, who examined Constance’s prison records, found that her brother wrote to her only twice as she was moved from prison to prison over the course of two decades. “Will you be kind enough to write to my brother and beg & entreat him to come and see me,” Constance wrote to an acquaintance in 1881. Her pleas had no documented effect.

In 1884, Huxley recommended Saville-Kent for a job as the inspector of fisheries for the former penal colony of Tasmania, and in May of that year Saville-Kent left England with his wife, Mary Ann, and his half-sister Mary Amelia. Though Saville-Kent was welcomed by colonial officials, he almost immediately butted heads with a local fisheries commission, whose members were preoccupied with the introduction of Atlantic salmon to the Pacific island. When his contract expired after three tumultuous years, Saville-Kent began hiring out his expertise to the Australian mainland, advising its colonial governments on the management of their mostly unregulated and fast-diminishing fisheries.

By this time, most of Saville-Kent’s immediate family had followed him to Australia. His half-siblings Acland, Florence, and Eveline all moved to the colonies during the 1880s. And in July 1885, after 20 years in prison, Constance Kent was released into the care of Reverend Wagner. Several months later, she seems to have emigrated to Australia alone. Some historians speculate that she reconnected with her brother, even living and traveling with him, while others believe that the two siblings had little or no contact. What is certain is that any secrets they shared remained secret.

Though Saville-Kent had been fascinated by corals since the beginning of his career, he didn’t see a living tropical reef until 1888, when he joined a surveying cruise along the northwestern coast of Australia. Few foreign naturalists had visited the area, and Saville-Kent, overwhelmed by the diversity of the tropics, immersed himself in collecting, painting, and drawing the vivid life forms he encountered. Shortly afterward, the colonial government of Queensland appointed him as its commissioner of fisheries, and he and Mary Ann moved to Brisbane. There, he surveyed the colony’s fisheries, helped reform their management, and began the work that would lead to The Great Barrier Reef of Australia.

When James Cook and the crew of HMS Endeavour had collided with the Great Barrier Reef more than a century earlier, they had also collided with some of the only humans who knew it well: The Guugu Yimithirr people did not take kindly to the crew’s appetite for green turtles, and they drove home their disapproval with well-aimed spears and boomerangs. As the British empire colonized Australia over the following decades, the reef became a colonial “possession” that was barely understood by its supposed possessors.

For most Europeans, after all, submarines and diving equipment were still fantasies from the imagination of Jules Verne, and their closest encounters with undersea life were in public aquariums like those that had once hired Saville-Kent. The ocean in general, and the vast Pacific in particular, provoked far more fascination and fear than protective concern; when the Saville-Kents arrived in Brisbane, colonists on the Queensland coast were reporting sightings of a giant shell-backed sea serpent they called the Moha-Moha. And while European naturalists had come to understand that coral skeletons were built and inhabited by invertebrate animals called polyps, the biology of corals was still largely unknown, and they hovered unsettlingly between plant and animal, animate and inanimate.

Saville-Kent, undaunted by the Moha-Moha, set out to probe the mysteries of the Great Barrier Reef. Dressed in a dark coat with a stiff collar, and with a cork helmet clapped on his head for protection against the tropical sun, he rolled up his trousers and waded into the surf, drawing and painting the coral outcrops he saw through the shallow water. When Mary Ann gave him a camera as a gift, he adapted a tripod into a frame that allowed him to photograph underwater corals from above, and he experimented with different lenses and filters in order to capture the sharpest possible images. When low tide arrived before dawn, he sometimes ventured into the ocean in the dark, photographing coral outcrops before the water rose. He toted his equipment up and down the coast, traveling from Brisbane to Thursday Island, part of the archipelago at the northernmost tip of Queensland. He made an especially close study of the coral genus Madrepore, identifying more than 70 species previously unknown to science. Everywhere he went, he noted the remarkable variety of life that composed the then-thriving reef.

Saville-Kent’s photographs were clear enough to serve as a benchmark for coral growth—a gift to not only naturalists but also navigators, who were eager to protect their ships from unmapped coral outcrops—and they were, perhaps, his greatest accomplishment. When The Great Barrier Reef of Australia was published in 1893, a review in Nature singled out “the diligence and skill of the author in photography” and predicted that the “magnificently illustrated” volume would “go far towards giving a realistic impression of some of the beauties of coral seas to the untravelled.” As Darwin had reflected during his own Pacific travels decades earlier, coral reefs “rank high amongst the wonderful objects of this world.” Despite the obstacles of distance and imperfect technology, Saville-Kent managed to share that wonder with many who would never experience it firsthand.

Two years after the publication of The Great Barrier Reef of Australia, the Saville-Kents moved back to England, but William continued to travel between England and Queensland until the fall of 1908, when he died suddenly at the age of 63. He was buried in a churchyard in the English village of Milford on Sea, just a few dozen miles from Rode, and his gravestone was decorated with coral skeletons from the Great Barrier Reef. In an obituary, the editors of Nature suggested that “Mr. Saville-Kent will perhaps be best remembered by his sumptuous work on the Great Barrier Reef of Australia.” They did not refer to the notorious crime that had shadowed his life.

While Saville-Kent succeeded in distancing himself from the murder of his young half-brother, the case and its unanswered questions were not forgotten. The first of at least six full-length books about the murder was published by a friend of Samuel’s in 1861, and a stream of pamphlets and essays rehashed the evidence. In 1929, the London publishers of The Case of Constance Kent, which had been written under a pseudonym by the detective novelist John Street, received a lengthy letter from Australia. The letter writer reported that Constance had died, but that before her death she had related the details of her early life. The writer insisted that Constance’s mother had not been insane, as Street had claimed, and that despite Street’s skepticism, Constance’s confession of her “most callous and brutal crime” had been genuine.

Street suspected that Constance herself had written the letter, but not until the 1980s would another author, Bernard Taylor, confirm that Constance, living in Australia under the pseudonym Ruth Emilie Kaye, had trained as a nurse and become a respected hospital administrator, even spending several years in charge of a ward for patients suffering from Hansen’s disease, also known as leprosy. She died in 1944, shortly after her 100th birthday, and her obituaries, like her brother William’s, made no mention of the murder of Saville Kent.

The exact circumstances of Saville Kent’s death are no clearer now than they were to Detective Inspector Jack Whicher in the summer of 1860. Noeline Kyle, in her 2009 book about Constance’s post-prison life, concludes that whether or not Constance actually slit her young half-brother’s throat, she came up with the idea—much as she came up with the plan for her and William to run away to sea—and therefore held herself responsible for his murder. But only the perpetrator, or perpetrators, knew the full truth.

The Victorian-era frustration with the Kent case found its most lasting expression in fiction. In the 1868 novel The Moonstone, one of the earliest modern detective novels, the crime, like that in the Kent case, takes place in an English country house, and the residents of the house are the primary suspects. The botched initial investigation is taken over by a taciturn detective from London, Sergeant Cuff, who unearths family secrets and focuses his attention on a missing nightgown. Initially, Cuff suspects the wrong person. But he eventually succeeds where Whicher failed, definitively identifying the guilty and providing a full account of motive and method. By doing so, he helps repair a shattered household.

The novel was enormously popular—it remains a satisfying read—and many of its ingredients are now familiar tropes. From Sherlock Holmes to Jessica Jones, fictional detectives can be relied on to wade into the messy aftermath of violence, spot the relevant evidence, and expose the perpetrators. In a way, the entire genre is a multivolume fix-it of the Kent case: Over and over, its heroes coax secrets to the surface, the certainty of their conclusions restoring something like order to the universe. Reality, of course, is rarely so reassuring.

Saville-Kent might have managed to keep one secret, but he was determined to share another. His innovative photographs of the Great Barrier Reef represented what the art historian Ann Elias calls an “emerging compulsion” among scientists and photographers to document living coral, and his successors would go to even greater lengths to expose reefs to a global audience.

In the 1910s and ’20s, the American explorer Ernest Williamson photographed Caribbean reefs at a depth of 150 feet from his “photosphere,” a chamber fitted with a funnel-shaped glass window and tethered to the surface with an air hose. The Australian photographer Frank Hurley, who in the 1920s followed Saville-Kent’s footsteps along the Queensland coast, built a surf-side aquarium in which he reconstructed underwater scenes in order to film and photograph them. By the mid-20th century, thanks to advances in diving technology, the curious could see living reefs firsthand, and underwater cameras allowed filmmakers to capture reefs in vibrant moving color. While the makers of today’s high-definition deep-sea documentaries are equipped with technology, and budgets, that Saville-Kent could only dream of, they are still surfacing the secrets of the ocean. In some ways, they have succeeded: While the ocean is still a place of mystery, it is better understood and less feared than it used to be.

But here, too, observation has its limits. Saville-Kent’s carefully framed photographs didn’t document the ravages of colonialism, or the industrial greenhouse-gas emissions that were already accumulating in the atmosphere. Hurley didn’t recognize that the coral polyps confined in his aquarium, stressed by the sun-heated water, were expelling their symbiotic algae, sacrificing both their color and their food supply in a process we now call coral bleaching. Neither could have imagined that in the early years of the 21st century, the ocean would grow warm enough to regularly bleach huge swaths of the Great Barrier Reef. Even today, the slow violence of climate change is often invisible, and resistant to scrutiny. But the identity of its perpetrators is no secret at all.

This article is part of our Life Up Close project, which is supported by the HHMI Department of Science Education.