Don’t Patronize Fetterman

The Pennsylvania Democrat deserves to face the same questions—and to be given the same opportunities—as any other candidate.

Earlier this week, John Fetterman sat down with NBC News for one of the defining television segments of the year. “Unlike any political interview I’ve ever done,” Dasha Burns, the NBC reporter who met with him, tweeted. Fetterman, the Democratic nominee for Senate in Pennsylvania, suffered a stroke in May. During this, his first on-camera interview since then, he relied on closed-captioning to process Burns’s questions. “I sometimes will hear things in a way that’s not perfectly clear,” he told her. “So I use captioning, so I’m able to see what you’re saying.”

When introducing her clip on NBC Nightly News, Burns told viewers that Fetterman seemed different during their off-camera small talk than he did during the caption-assisted interview. “It wasn’t clear he was understanding our conversation,” Burns told the anchor Lester Holt. The following morning on Today, Burns went a little further, telling the host Savannah Guthrie, “Without captioning, it seemed it was difficult for Fetterman to understand our conversation.” When Guthrie pressed her on that specific observation, Burns backpedaled. “Stroke experts do say that this does not mean he has any cognitive impairment,” she said. She noted that he didn’t appear to have trouble understanding her questions with the assistance of captions.

Part of our culture’s ongoing stigmatization of disability stems from our profound lack of understanding about the variability—and spectrum—of physical and mental challenges. Day after day, we stigmatize disabled Americans, but we also jeer at our fellow citizens who even present as disabled in some minor way. Liberals once ruthlessly mocked the halting manner in which Donald Trump descended a ramp. Because Trump did not walk normally, in their view, something was of course wrong with him—further evidence he was unfit to be president. Conservatives, for their part, continue to attack Joe Biden because he manages a stutter and does not speak “normally.” Fetterman, who has dealt with auditory-processing issues and has exhibited muddled speech since his stroke, is likewise the subject of troubled stares, jokes, and questions about his fitness to serve in the U.S. Senate.

Armchair medical diagnoses plagued the Trump era, and they have yet to abate during the Biden years. As soon as the interview aired, social-media commentators moonlighting as medical experts stepped in to express their concerns about Fetterman’s cognitive capacity—even though Burns herself had noted that experts caution against drawing such conclusions. Nor did Fetterman’s stroke suddenly make him deaf. He appears to be struggling with auditory processing—a complex system involving the ears, brain, and speech muscles. During the NBC interview, Fetterman wrestled with the word empathetic. His brain knew that empathetic was the word that belonged in the sentence. But he struggled to produce that word sonically. As time goes on, these blips may become less frequent for him—or they may stick around for the rest of his life.

As some commentators attacked the segment for stigmatizing disability, Burns appeared to grow defensive of her framing of the interview. Kara Swisher and Rebecca Traister, two journalists who also recently interviewed Fetterman, disputed Burns’s characterization of his performance. “It’s possible for two different reporters to have two different experiences [with] a candidate,” Burns tweeted in reply to Swisher. By midday Wednesday, when NBC posted the full segment on YouTube, the network’s packaging of the story seemed to shift: “Full Fetterman Interview: ‘I Believe I’m Going to Be Able to Serve Effectively’ After Stroke.”

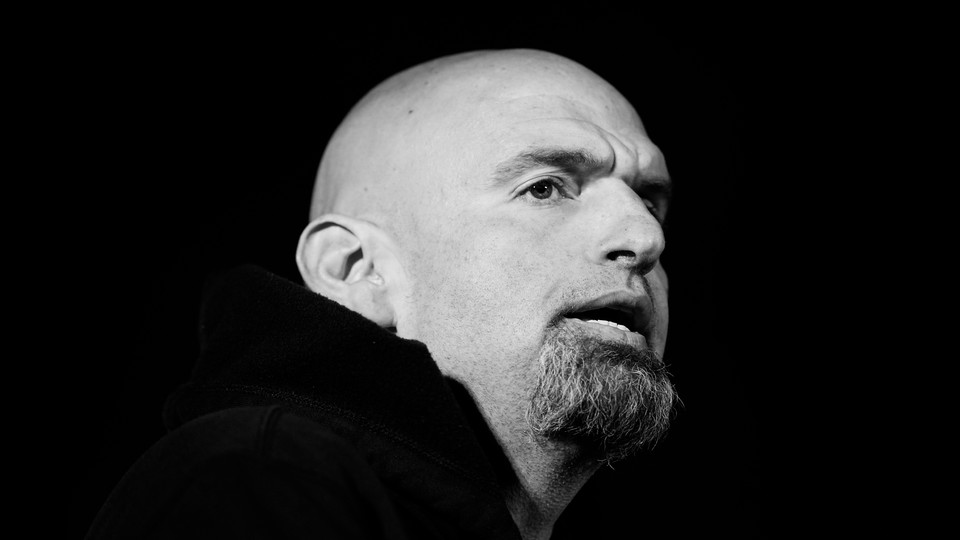

Fetterman, like every politician, is trying to sell the voting public on an idealized version of himself. Every decision his campaign makes is calculated. Before becoming a U.S. Senate candidate, he was Pennsylvania’s lieutenant governor, where he differentiated himself by posing for his official portrait in a gray work shirt—no tie, no blazer, no lapel on which to pin a flag. Years before that, as mayor of Braddock, he welcomed Anthony Bourdain into his Rust Belt town and, like the late TV host, spoke in a gruff, no-nonsense, down-to-earth manner. He marketed himself as the kind of guy you’d want to have a beer with, maybe watch a Steelers game with. This pose of normalcy was at the center of Fetterman’s appeal, and it’s what propelled him to victory during the Democratic primary.

Fetterman still dresses more casually than just about any other politician, but since his stroke, his communication style has undoubtedly changed. CBS News’s Ed O’Keefe asked a provocative question after watching the NBC clip: “Will Pennsylvanians be comfortable with someone representing them who had to conduct a TV interview this way?” O’Keefe’s musing reveals a larger truth about our politics and our culture: No matter how often we celebrate the Americans With Disabilities Act, no matter how far the grassroots disability-pride movement has come, many Americans still look down on those whose bodies and patterns do not conform to their expectations.

Fetterman is a 53-year-old man with a Harvard education who has put himself on the national stage; he is not a child or charity case, and does not need to be treated as such by members of the media. By running for Senate, he has opened up himself, his policies, his past, and his present for intense scrutiny. Given that he experienced a major medical issue this year, Fetterman’s campaign would be wise to release his medical records to further inform the public about his auditory-processing issues and to quell speculation about his general mental acuity. The media are justified in asking questions about a candidate’s health, particularly when the matter is partly neurological. What’s unfair is expecting that Fetterman’s disability should be accommodated only when the cameras are rolling.

Admirably, he is not hiding the fact that he had a stroke, yet he has found himself in an unsustainable gray area regarding his communication. Fetterman and those around him are trying, and failing, to have it both ways. On one hand, Fetterman is being matter-of-fact about his need for accommodations such as captioning. On the other, he’s clinging to an antiquated message centered on recovery—he clearly wants voters to know that he’ll eventually get better. The truth is, he might not. A simpler and more honest approach might be to say that he has acquired a disability—and that regaining his old “normal” is not the only path to success, or the Senate. But is that a message voters are ready to hear?