Why are some societies warlike, and why are some peaceable? New scholarship suggests that societies can be arranged in a spectrum ranging from domination-based to partnership-based. Every relationship in a dominator society, whether between parent and child, husband and wife, political leader and citizen or citizen and noncitizen, is authoritarian and coercive, whereas in a partnership society, relationships are life-sustaining and egalitarian. Further, dominator societies—the canonical example of which is Nazi Germany—are warlike and propelled by trauma, whereas partnership societies are more caring and peaceable. And childhood experiences help explain how such societies arise and perpetuate themselves.

Social systems scientist Riane Eisler, one of the most original thinkers of our time, and anthropologist Douglas Fry pull together insights from psychology, social science, anthropology, neuroscience and history to make this case in the book Nurturing Our Humanity(Oxford University Press, 2019). “This whole-system approach,” Eisler says, “recognizes that families do not arise in a vacuum but are embedded in, affect and are affected by the larger culture or subculture of which they are part.”

Nurturing our Humanity synthesizes ideas that Eisler, now in her early 90s, developed over a lifetime of research and sketched out in her best-known book, The Chalice and the Blade (HarperCollins, 1987). Described by one commentator as the “most important book since Darwin’s Origin of Species,” this pathbreaking work expanded upon the discoveries of pioneering archeologist Marija Gimbutas and others to posit that early European societies, such as the Minoan civilization, were led by priestesses but were egalitarian rather than matriarchal. Far from representing the flip side of patriarchy—with one gender still dominating another—these societies, Eisler argued, were partnerships in which men and women enjoyed nurturing relationships of equality, prosperity and peace with one another and with their neighbors. Starting around 6,500 years ago, these “partnership” societies were destroyed by invasions that converted Europe to patriarchal and warlike “dominator” societies that have since prevailed.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“In the course of this work, I realized how traumatized I had been by political and social events,” Eisler says. “I also began to see how families that cause trauma are, and have long been, a mechanism for reproducing authoritarian, punitive, violent, male-dominated cultures.” In 1987 Eisler and her husband, David Elliot Loye, founded what is now called the Center for Partnership Systems, which seeks to propel society toward a partnership-oriented system. Scientific American spoke with Eisler about her decades of investigation.

[An edited transcript of the interview follows.]

How did your childhood experiences influence your lifelong quest to understand the inner workings of society?

As a child, I witnessed great evil, but I also witnessed spiritual courage because my mother stood up to the Nazis. It was on Kristallnacht, the Night of Broken Glass. I was seven years old and at home with my parents in Vienna. For some reason, my mother didn’t send me to school that day. Things were very tense by then. I’d already seen how bearded old Jews were made to scrub the sidewalk right by our house, on their knees, by Nazis who laughed at them.

My father had a wholesale cutlery business, and my mother worked there. When the Nazis came that night, she recognized one of them as a former errand boy of the business. He was an Austrian Nazi, one of those who welcomed Hitler’s invasion of Austria. She got furious at him. She demanded, “How dare you do this to this man who has been so good to you?”

I have blocked so much of the actual memory, as people who are traumatized do. All I know is that they were there, and they pushed my father down the stairs. There were about five of them. Some were in uniform. My mother could have been killed for challenging them, but instead the head of the operation said to my mother, “Give us this much money. I can’t give him back to you now, but if you bring it to Gestapo headquarters, I’ll give him back to you.”

My mother obtained not only my father’s release but also a safe conduit. If they came back for him, she could show them a document that meant that he was not to be taken away. If it hadn’t been for her, my father would have been taken to a concentration camp. He would never have been released. And we would have waited, and eventually we would have been taken away, too. So my mother basically saved all of our lives.

You could have cut the fear in our home. People my parents knew had been killed. My parents desperately wanted to leave. But they had a sort of a catch-22. You couldn’t get steamship tickets out of Europe until you had a visa somewhere. And you couldn’t get a visa until you had a steamship ticket. It just calls for bribery. My parents weren’t rich, but fortunately they had the money to do that.

Riane with her parents, Lisa Greif and David Abraham Tennenhaus, in Vienna in 1938. Credit: Courtesy of Riane Eisler

They had an acquaintance in New York, and they were on the phone, trying to get some kind of guarantee that they wouldn’t be a burden. But they couldn’t get into the U.S. because they were born in [the region of] Bukovina, a part of the Austrian Empire that became Romania after World War I [and that is now in present-day Romania and Ukraine]. There were only two places in the world where Jews who couldn’t get into the U.S. were admitted; one of them was Cuba. And we eventually got entry papers for Cuba.

How long were you in that house waiting for papers to come through?

We waited a couple of months in our apartment, which had blue velvet curtains that I remember because I loved the feel of them. I remember our fleeing very well because it was at night, with only what we could carry. My mother was so traumatized that she forgot her jewelry at home. So distant relatives went back for it—two people who I think were both later killed. They came back with the jewelry, and one of them lit a cigarette, and it somehow set my hair on fire. Who can forget that?

We got on a train to Paris. I remember being in a hotel room in Paris, all alone, because my parents had to go to some consulates, and I was so afraid that they wouldn’t come back. We went to see the movie Snow White, and I was terrified because I was a traumatized child already. I don’t know what terrified me. It was in English, which I understood because they sent me to a bilingual kindergarten.

When we arrived in Cuba, my mother sold some of her jewelry so that I could go to a private school, Central Methodist School. And then when it was time to go to high school, they sent me to another private school in the suburbs. This one was run by some British women who were also bilingual.

But I was always an outsider. Being an outsider was very, very hard, but I would say that it served me well because it made it possible for me to think outside the box. I very early realized that what we consider “just the way things are” is not the same everywhere. It’s one way in Vienna, another in Cuba and yet another in the U.S.

There was a lot of antisemitism in Cuba. I remember standing at the pier, looking out at the ocean liner St. Louis. We were on one of the last ships before Cuba turned the St. Louis back [with Jewish refugees from Europe]. There was a movie made about the St. Louis called Voyage of the Damned. And they were damned—nobody, not the U.S., no country in the Western Hemisphere would let them land. They all had purchased entry permits, just as we had, but suddenly, in collusion with the Nazis, they were turned back.

We stayed in the industrial slums of Havana. It was terrifying. There were street children yelling, “Polaca!” at me. I was Austrian, Viennese, but the first Jewish immigrants had been from Poland, and the Nazis fomented a tremendous campaign against Jews.

I had some friends at school, but I couldn’t bring them to my home in the slums. My high school was an exclusive school where wealthy Cubans’ children got an English education.

But there was one early class by a teacher named Mrs. Kirby in Central Methodist School. She gave me the first inkling that there was such a thing as prehistory. And I was absolutely fascinated. I was a very curious child. In the Bible, it says, “Henceforth, women will be subservient to men.” And I always wanted to know: What was it like before the “henceforth”?

Didn’t you get any Jewish religious training?

Yes, because my parents found out that I had to go to chapel. You see, I was in a Methodist school. I got so tired of being the only kid that didn’t raise their hand when asked, “Do you believe in Jesus?” I mean, how old was I? Eight or nine. So I raised my hand, and my parents got wind of this, and they hired a rabbi to teach me that I’m Jewish. Obviously, I was very well aware that I’m Jewish, I mean, after all that had happened.

I asked the rabbi what it was like before the “henceforth.” And he didn’t like that. I also wanted to know why, in the story of Eve and Adam, Eve asked a snake for advice. I later discovered the answers to my questions. Snakes were a symbol of oracular prophecy. Remember the Oracle of Delphi [in Ancient Greece]? She worked with a snake to put herself in an oracular trance. Eve asked the snake for advice because that part of the story was the old reality, when women were asking, as priestesses, for oracular advice from a snake.

Can a snake bite give you a transcendental experience?

I believe so. Remember the Minoan goddess-priestess figurines—they have snakes coiled around their arms and are in an oracular trance.

Let’s get back to your story.

Eventually we did come to the U.S., and I remember the disappointment. In Florida, which was our landing point, the segregation and the poverty were awful. We moved to New York City, and it was really overwhelming for all of us. Then we settled in Los Angeles.

I went down to the L.A. Board of Education and explained to them that I didn’t want to finish 10th grade, and I asked if they could please let me into 11th grade. They did, and it was a terribly boring time, because my education up to that point had been really good. In college I majored in anthropology and sociology, and then I started law school.

I wanted to leave home. My parents informed me that a good Jewish girl only left home when she’s married. So I got married to someone I had nothing in common with. We were both traumatized. He was a Hungarian refugee. I was an Austrian refugee. I wanted love. He dealt with trauma by becoming divorced from feelings. We had two wonderful daughters, but I had no skills for parenting.

I was a homemaker in the suburbs of Los Angeles, and I was fascinated with the Eleusinian mysteries [a secret rite in ancient Greece that initiated people into the cult of Demeter and Persephone]. Demeter has a daughter, Persephone, who has to go to the underworld for six months. And that’s why we have winter: it’s cold and dark for six months because Demeter, who is the goddess of the earth, is in mourning. When Persephone comes back, it is spring and summer. And I began to wonder:How is it that we’ve never been taught about powerful women?

Then the questions of my childhood came up because I always wanted to know, “Does it really have to be this way?” I witnessed the terrible cruelty and violence of the Nazis. But I also witnessed love because my mother stood up against injustice out of love. And so the question was: When we have the capacity for both of these things, what has pulled so much of so-called civilization toward destructiveness? That’s really when I started the research for TheChalice and the Blade.

Did you write the book while you were at home with the children?

No, no. My life is like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle coming together. I went back to law school on my way out of my first marriage because I needed a meal ticket. I got a part-time job as an attorney because I had little children. I quit my marriage, my job and smoking within three months and threw myself into the counterculture. It was like a rubber band stretched to its limits, breaking.

I’d always thought there was something wrong with me because I didn’t fit into this role of the little woman behind the successful man. We’d go to cocktail parties, which was the thing you did in those days, and they’d ask you, “What do you do?” And I’d say, “I’m just a housewife and a mother,” as if this were nothing. I thought of myself that way until the late 1960s, when I suddenly woke up.

I wrote a play, Infinity, and then a screenplay. And I got a contract to write Dissolution: No-Fault Divorce, Marriage, and the Future of Women [McGraw-Hill, 1977]. It was around 1969, 1970 when the feminist movement got going. I became very, very active in the women’s and feminist movement. I backed into divorce law through the Los Angeles Women’s Center Legal Program, which I founded. I predicted that no-fault divorces would lead to what was later called the feminization of poverty. When middle-class women used to get divorces, they always got alimony because there was a fault. No-fault divorce was a fairer law because fault had often been made up—but it wasn’t a level playing field. What happened with no-fault divorce was that women were not getting alimony and were dropping into poverty with their children because the work of care that women did wasn’t valued or paid.

After that book, I had a physical and mental breakdown. My father died suddenly, and I’m an only child. And that was a fraught relationship. I went back to Dachau. I had to see [the concentration camp]. And I read the book Treblinka [by Jean-François Steiner]. I just had to get into what really happened.

In a sense, that was healing. But six months after my father died, I found my mother sitting dead by the phone trying to ask for help. She’d obviously had a heart attack. And I wasn’t there to help her. I became terribly depressed. I had to give up my law practice and give all my clients to somebody else. I couldn’t do it anymore.

Then I met David [Elliot Loye]. We fell in love, and we spent the next 45 years literally together. He really saved my life. I didn’t want to tell him how sick I was. But he knew, and he decided that it was his mission to make me whole. I was writing The Chalice and the Blade, but I didn’t really show it to him until 1984. I was invited to the former Soviet Union to be one of two American delegates to Nordic Women for Peace. In case something happened to me, I left the manuscript with him. And he loved it.

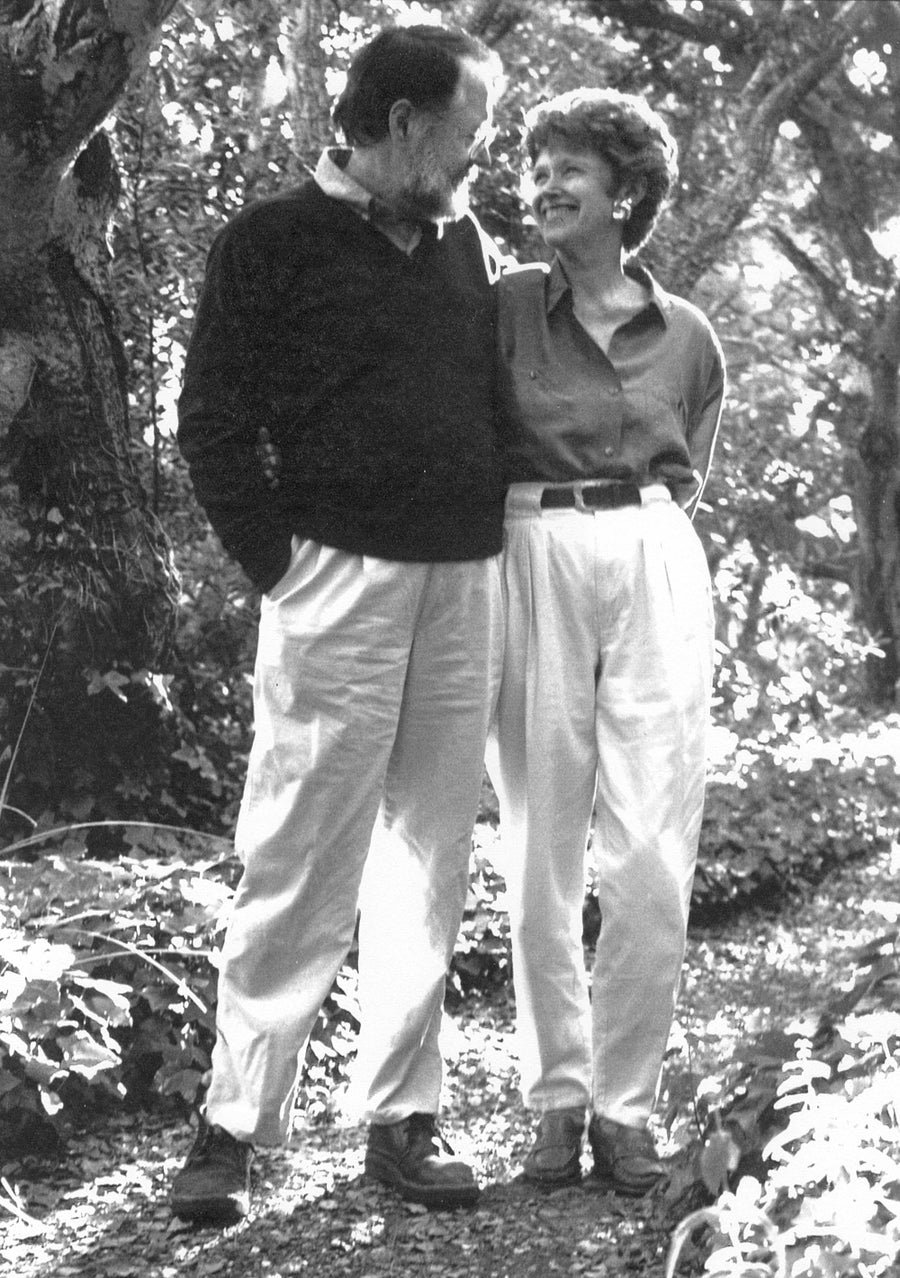

Riane Eisler with her husband, David Elliot Loye, in their garden in 2000. Credit: David Loye

It was three times as long as the published version, and he helped me cut it. He just believed in me. He had a Ph.D. in social psychology, and I learned a lot from him. And of course, Chalice made a splash. A lot of books are now coming out going over the same kind of territory, basically showing that there were what I call partnership-oriented societies for millennia.

How did you shift from focusing on patriarchy to domination in society?

I realized there never was a matriarchy. The whole idea that the opposite of patriarchy is matriarchy is just another side of a domination coin.

The first two books that I wrote on the topic, TheChalice and the Blade and Sacred Pleasure, were me trying to figure out: How did it get to this crazy place? Sacred Pleasure foreshadows everything else I’ve written. It is very personal. And it is about how sexuality and spirituality were transformed by domination. It was at that point that I started to really think about children. And then I wrote a book on education—because I had to know: How do we change this? Education is one of the mechanisms for perpetuating social norms. That book is Tomorrow’s Children.

Then I wrote a book that won a Nautilus Book Award for being the best self-help book of the year: The Power of Partnership. It looks at seven relationships and how they’re different, depending on the degree of orientation to either end of the partner-domination scale. It starts with how we relate to ourselves, and then it examines our family and intimate relations, our work and community relations and relations with nature because it’s all of one piece.

After that came The Real Wealth of Nations. I proposed an economic system that considers nonmarket work. The problem isn’t socialism, and it isn’t capitalism—it’s that the ethos behind both is the domination ethos. Both Adam Smith and Karl Marx accepted the distinction between “just” reproductive work and productive work. And they both focused on the market. For them, the work of caring for children, starting at birth, was supposed to be done for free by a woman in a male-controlled household and hence is called reproductive. In the Real Wealth of Nations, I point out that both socialism and capitalism leave out the three life-sustaining nonmarket sectors of the economy: the natural economy, the volunteer community economy and the household economy.

When Marx wrote during the 1800s, do you know that a wife could not sue for injuries that were negligently inflicted on her? Only her husband could sue—for loss of her services. People don’t know their history, much less their law. You can use the law to maintain domination. Or you can use it to move toward a more egalitarian, more peaceful, more gender-balanced world. And so my theme in Nurturing Our Humanity has been that what children experience or observe is primary, and it isn’t just a children’s, just a family, issue. It’s a social and economic issue. And I think that’s one of my most important contributions, frankly.

What role does trauma play?

I didn't really start thinking about trauma until I did the research for Nurturing Our Humanity. The adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) studies on the long-term negative consequences of childhood adversity were revelatory. In my eclectic, whole-systems way, I came across the work of [psychologists] Michael Milburn and Sheree Conrad, which documented how children from punitive families are often drawn to political leaders who deflect repressed pain and anger against those they perceive as weak and evil. Milburn and Conrad found that this punitive agenda is especially pronounced in men. They attribute this to a male socialization that requires men to deny fear, pain, and empathy and focus instead on anger and contempt as culturally appropriate “masculine” emotions.

Gender socialization makes people equate the differences between them with dominating or being dominated, with superiority and inferiority, with being served and serving. Given this connection between difference and domination, it’s not coincidental that you have antisemitism or that you have racism. There is always an in-group and an out-group.

How does the system reproduce itself?

By observation and by experience. It’s a very punitive family, the dominator family. I think what happens in a traumatized child is denial and identification, instead, with the strong parent and blaming of the weak child. The denial—that there’s anything bad that your parents or your caregivers did to you—is then channeled through this in-group versus out-group thinking that domination-oriented religion provides. It is a mixture of psychological mechanisms of denial and of displacement. You can’t acknowledge that the people on top, whom you depend on for food, a roof over your head and the care you get, are punitive.

This confluence of caring and coercion is lethal. It causes the displacement to the out-group. But the out-group, except for the out-group of women, varies. I think we’re all traumatized by the domination system, frankly. And what passes for normal in some communities is a traumatized state.

We urgently need new partnership norms that recognize scientific findings that “human nature” is very capable of caring. Whether this capacity is or is not expressed is determined not by genes alone but by the interaction of genes with our environment, which for humans is primarily the cultural environment. So it became my life’s mission, along with David’s, to propagate more caring partnership cultures that value and reward the “women’s work” of caring.

David was the love of my life, my partner and my best friend. And he died last year, two days after the 45th anniversary of the day we met, which we always celebrated. Still, I’m blessed because I live in a beautiful place, and I am still able to think and to write and to do things.