Jalen Hurts and Patrick Mahomes Had to Disprove a Misconception

A historic Super Bowl matchup defies professional football’s reluctance to let Black athletes call plays.

The number of Black quarterbacks has soared in the NFL over the past 25 years, and it was only a matter of time before two of them faced each other in the Super Bowl.

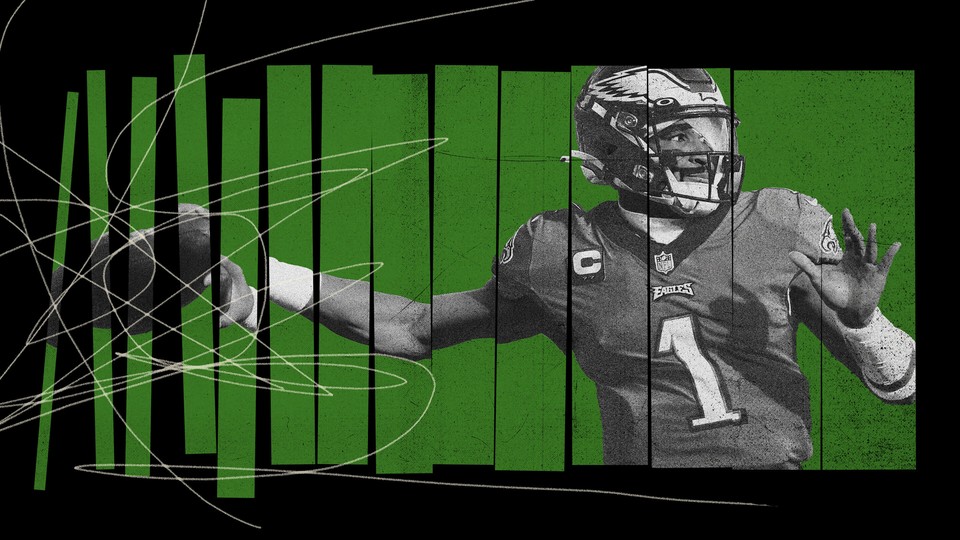

Sunday’s championship game will pit the Kansas City Chiefs’ Patrick Mahomes against the Philadelphia Eagles’ Jalen Hurts. Only seven Black quarterbacks have played in a Super Bowl, and just three—including Mahomes—have won. That a record 11 NFL teams had Black starting quarterbacks on opening day of the current season suggests that matchups like this year’s will soon be commonplace. But the fact that no such game has taken place before Super Bowl LVII underscores the plight of the Black quarterback for most of the NFL’s century-long history.

Even though most NFL athletes are Black, most teams have been slow to put Black men in a position to call plays. The Eagles, to their credit, have been more willing to offer opportunities than other teams. “I think about all of the [Black] quarterbacks that came through Philly: Randall Cunningham, Rodney Peete, Donovan McNabb, Mike Vick,” Hurts told reporters during a pre–Super Bowl media session. “This franchise, the history we have of African American quarterbacks—that speaks for itself. I told those guys I want to carry that torch for them.”

Like Black Americans in general, Black players in the NFL have long struggled to have their talents and aspirations taken seriously. In 1920, Fritz Pollard became the first Black quarterback in what was then known as the American Professional Football Association. In his rookie season, Pollard led the Akron Pros to the league championship. But in 1934, the NFL banned Black players at the initiative of the former Washington owner George Preston Marshall, who once said, “We’ll start signing Negroes when the Harlem Globetrotters start signing whites.” The ban remained in place for 12 years.

When the NFL reintegrated in 1946, the prevailing assumption was that Black athletes weren’t intelligent enough to play quarterback. Run and tackle? Yes. Be the face of a franchise and give direction to other men? No.

In his 2022 book, Rise of the Black Quarterback: What It Means for America, the sportswriter Jason Reid interviewed the former NFL player John Wooten, who co-founded the Fritz Pollard Alliance, an organization dedicated to creating equal opportunities in the NFL. Wooten told Reid,

Your quarterback is really the guy everyone was supposed to follow on the field. But you have these coaches who not only thought we couldn’t play there because we supposedly weren’t smart enough, which was just racist and ridiculous, but the leadership part of it was even a bigger problem for them. They just couldn’t see us being the leaders of teams all over the league. You look back at that time, you just didn’t see any of us at quarterback. Even the few guys who did break through a little, they didn’t really get opportunities. And they didn’t last long.

That was true of Marlin Briscoe, professional football’s first Black quarterback in the modern era. Briscoe was slated to play defense for the Denver Broncos in 1968, but the Broncos’ offense was in such disarray that then-coach Lou Saban gave Briscoe a shot at the coveted signal-caller position. Briscoe excelled, leading the team in passing yards and touchdowns. Despite his success, the Broncos gave him little playing time the next season; he later asked to be released. Briscoe finished out his eight remaining years in the NFL at wide receiver, illustrating the common practice of Black athletes being forced to change positions because they weren’t going to get a fair shot at playing quarterback.

Also underappreciated was Warren Moon, now the only Black quarterback in the NFL Hall of Fame. After going undrafted following a spectacular career at the University of Washington, Moon opted for the Canadian Football League. It was only after Moon dominated the CFL by winning multiple championships that the NFL sought him out. He went on to flourish for 17 years as one of the most prolific passers in league history.

The current landscape is much more welcoming than what Briscoe and Moon experienced, but today’s Black quarterbacks are still subject to the same stereotypes and double standards that afflicted their predecessors. Hurts, for example, faced a lot of nonspecific criticism before this season began. Influential commentators hinted that Eagles insiders were “not very comfortable” with him and mused about “what his ceiling is” and whether “he’s already closer to reaching it than most would like to admit.” All quarterbacks are second-guessed, but the supposed discontent about Hurts, in just his second season as the Eagles’ full-time starter, was unusually vague.

The Baltimore Ravens quarterback Lamar Jackson is the fourth Black quarterback to win the league MVP, but if some NFL decision makers had it their way, he never would have played quarterback at all. Despite winning a Heisman Trophy at the University of Louisville, Jackson was asked to run drills as wide receiver at the 2018 NFL scouting combine. An anonymous defensive coordinator told The Athletic last summer that if Jackson “has to pass to win the game, they ain’t winning the game.”

Another team with a Black quarterback went out of its way to express distrust in him. The Arizona Cardinals initially put a “homework clause” in Kyler Murray’s recent $230.5 million contract extension. The clause stipulated that Murray had to study game material for four hours a week on his own without being distracted by the TV, internet, or video games. If Murray violated the clause, he was at risk of defaulting on his contract. After intense public criticism, the Cardinals removed the clause, which was right in line with the antiquated perception that Black athletes weren’t smart or disciplined enough to play the marquee position.

None of this minimizes the significance of the progress that Black NFL players have achieved. But the history that Mahomes and Hurts will make in Super Bowl LVII is also a reminder that progress hasn’t come easily.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.