Kids Deserve Privacy Online. They’re Not Getting It.

Today’s children face a world of constant surveillance. Their very sense of self is at stake.

Listen to this article

Produced by ElevenLabs and News Over Audio (NOA) using AI narration.

Childhood is the crucible in which our identities and ambitions are forged. It’s when we sing into our hairbrushes and confide in our diaries. It’s when we puzzle out who we are, who we want to be, and how we want to live our lives.

But to be a modern child is to be constantly watched by machines. The more time kids spend online, the more information about them is collected by companies seeking to influence their behavior, in the moment and for decades to come. By the time they’re toddlers, many of today’s children already know how to watch videos, play games, take pictures, and FaceTime their grandparents. By the time they are 10, 42 percent of them have a smartphone. By the time they are 12, nearly half use social media. The internet was already ingrained in children’s lives, but the coronavirus pandemic made it essential for remote learning, connecting with friends, and entertainment. Watching online videos has surged past television as the media activity that kids enjoy the most; children cite YouTube as the one site they wouldn’t want to live without.

That children need special protections online and everywhere else is obvious. And indeed, under the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA), web platforms and creators of digital products are required to obtain parental consent before collecting and sharing digital identifiers (such as location, email, and device serial number) that can be traced back to a child under the age of 13.

COPPA was passed in 1998. Compliance is largely voluntary, and evidently spotty. In 2020, when researchers studied 451 apps used by 3- and 4-year-olds, they found that two-thirds collected digital identifiers. Other research suggests that children’s apps contain more third-party trackers than those geared toward adults. And even if an app or product is COPPA compliant, it can still collect highly valuable, potentially identifying information. In today’s hyper-aggregated digital landscape, every nugget of information can easily be stitched together with other information to create a richly detailed dossier that clearly identifies you in particular.

The harvesting process, it’s important to note, tends to be automated and indiscriminate in what information it collects. A company can amass private information about your child even when it doesn’t intend to. In 2021, TikTok rewrote its privacy policy to allow it to gather “voiceprints” and “faceprints”—that is, voice recordings and images of users’ faces, along with all of the identifying information that can be gleaned from them. And we know that at least 18 million of TikTok’s U.S. users are likely age 14 or younger. It’s not difficult to imagine that children would sometimes share sensitive personal information on TikTok, whether TikTok intended to collect that information or not.

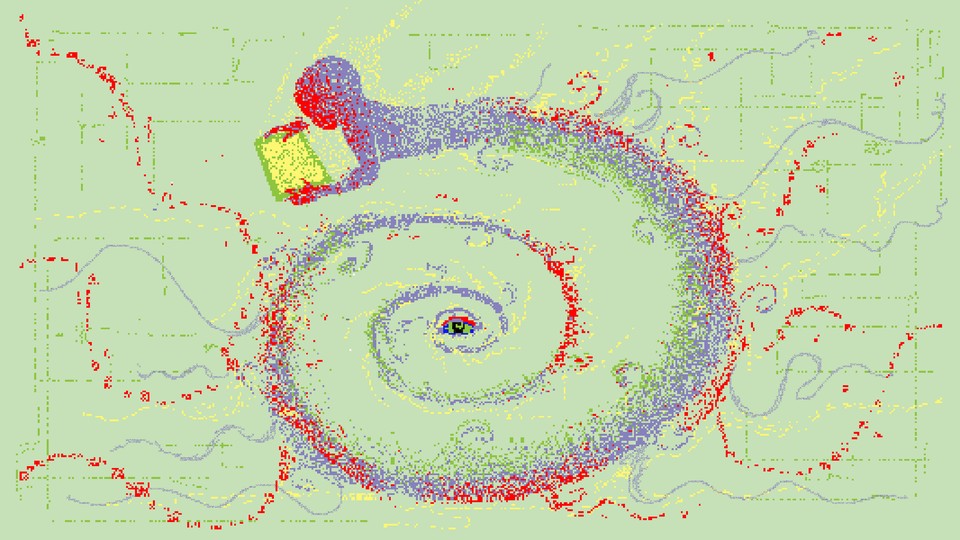

You get the picture; it’s bleak. All in all, by the time a child reaches the age of 13, online advertising firms have collected an average of 72 million data points about them. That’s not even considering the degree to which children’s data are shared and their privacy potentially compromised by the people closest to them—sometimes in the form of a grainy sonogram posted to social media before they are even born. As of 2016, the average child in Britain had about 1,500 images of them posted online by the time they hit their fifth birthday.

We typically take it as a given that adults have a right to decide, for ourselves, who is allowed to know our private thoughts, utterances, and actions. Kids have this right too. All human beings need privacy if we are to entertain thoughts, communicate these thoughts with trusted others, and act on these thoughts without fear of interference, judgment, or censure.

Young children may not grasp the importance of privacy, but they deserve it, and have a right to it, just the same. As their guardians, parents therefore have the primary responsibility to act on their children’s behalf and secure their privacy interests as best they can on an internet whose regulations don’t meet reality. Parents should protect children from bad actors and steer them toward good practices, and help them understand that once a photograph or piece of information leaves them, it is, in a sense, no longer private.

This means parents should be thoughtful about what they themselves share on social media. It’s helpful here to distinguish between information that’s private and information that isn’t. An example of the latter is your child’s team winning a soccer match, which anyone who attended the match would know; as such, sharing a photo of their match on Instagram or a parent WhatsApp group would be fine. Also helpful is remembering that when you do share private information about your child online, you should do so primarily with your child’s interest in mind. And as children grow older, their capacity to make decisions for themselves also grows. Parents should try to give progressively more weight to the child’s perspective when deciding whether or not to share private information about them. If your 17-year-old asks you not to tell other people which colleges she is applying to, then, even if you believe that crowdsourcing your friends on Facebook could enable you to better assist her with her application, you should probably respect her wishes.

The digital age has opened up new worlds for kids, but it has also threatened their ability to shape the course of their lives. Today’s children are in danger of growing up while having their every move tracked, stored, cataloged, and used by the largest and most powerful companies on Earth. We must protect their ability to grow up on their own terms.