No question is more dreadfully pretentious than “What is art?” except possibly “Can you come see my one-person show?” Yet I’ve accepted that at some point in the course of a life, both will need to be answered. Because I’m a writer facing the advent of ChatGPT, the time for the first question is now.

Most people (including some writers themselves) forget that creative writing is an art form. I suspect that this is because, unlike music or painting or sculpture or dance—for which rare natural aptitude straightaway separates practitioners from appreciators—writing is something that everyone does and that many people believe they do well.

I have been at parties with friends who are dancers, comedians, visual artists, and musicians, and I have never witnessed anyone say to them, “I’ve always wanted to do that.” Yet I can scarcely meet a stranger without hearing about how they have “always wanted to write a novel.” Their novel is unwritten, they seem to believe, not for lack of talent or honed skill, but simply for lack of time. But just as most people can’t dance on pointe, most people can’t write a novel. They forget that writing is art.

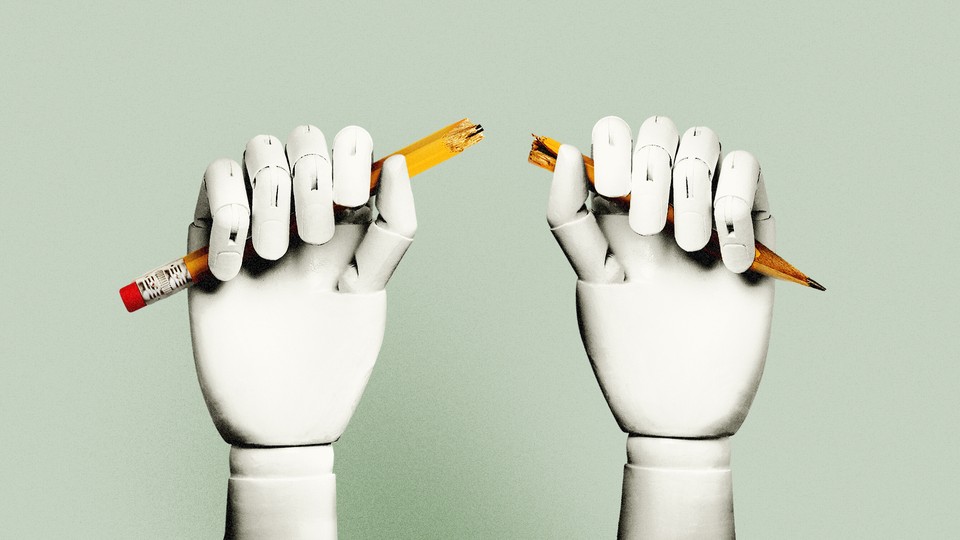

Art plumbs the depths of human experience and distills the emotions found there. That’s hard work, which inherently—and perhaps conveniently for me—can be done only by a human. This doesn’t mean that all art humans make is effective or good, nor does it mean that a computer cannot generate content that might entertain or inform. A computer alone can’t make art. But it can, I expect, make “good writing.”

The rise of ChatGPT forces us to think about this distinction between art and good writing—or “craft,” as we’re taught to call it. For most writers, the path to publishing involves writing-preparatory programs—workshops and private writing classes and M.F.A. programs—that are structured around the mastery of writing as a craft. But if we want human writing to survive as an art (and as a profession), these programs need to reassess their priorities because they are facing an existential crisis.

I was 41 when I took my first intensive writing course during a week-long summer workshop. Its structure, I’d come to learn, was largely based on the same pedagogical model as most M.F.A. programs: an instructor-led workshop, where we would evaluate one another’s stories, supplemented by craft talks. I found my writing so improved by the course that I wanted more. By the following year, I was enrolled in a master’s-of-fine-arts program.

I loved graduate school. I had instructors who changed how I thought about writing and my art and who I could be as an artist. But I found myself occasionally frustrated, and one particular incident from my last semester sticks in my mind.

It was the pandemic, and we were workshopping a classmate’s story that, we all agreed, wasn’t “working.” On the Zoom, we danced around the reason, but privately, in a smaller chat, some of us were more frank: The author was evading the real reason their character seemed so distressed. In other words, the story was a well-written pile of emotional bullshit.

Encountering this in a story feels the same as hearing a well phrased but feeble excuse in real life: You might accept it, but you’re not buying it. Yet the professor’s advice was all about cleaning up the point of view and adding more action. In short, mechanical fixes for an emotional problem.

Maybe the endless Zooming had finally gotten to me, or maybe it was the impatience that has struck me post-40, but suddenly I unmuted and blurted out: “I’m sorry, is this a master’s in fine arts or a master’s in fine mechanics? The sentences could be perfect, but it won’t fix the fact that the story isn’t being honest.”

To which my professor replied, “What’s wrong with being a good mechanic?”

The answer, of course, is nothing. Writing beautiful, clear sentences that string together into gorgeous paragraphs that assemble into elegantly constructed narratives requires discipline and discernment and technical understanding. My work as a novelist has absolutely benefited from the improvement of my technical skills. But literary art is not about the mechanics of sentences. It’s about how those sentences support emotional honesty.

You can dissect great writing without ever analyzing or even discussing the emotions involved or evoked, and walk away with some craft strategies to deploy in your own work. But a machine can do that too. It can read—it has read—the same great writers I have read. It can (and is beginning to) learn all of the clever lessons of craft. It will almost certainly become capable of producing what many M.F.A. classes would consider “good writing.”

But if that’s the case, maybe that “good writing” isn’t so good after all. If this new technology makes such writing ubiquitous, that writing may as well be obsolete.

If we want to push the art of writing out of a computer’s reach, the questions posed in writing workshops should go past “How could this piece work better?” to “How could this piece be more honest? More emotionally effective? More resonant?”

These are tougher questions, not only because they’re more subjective, but because they require skills that go beyond the command of language: insights into human nature, imagination, innovation, creativity, a mastery of pathos, ethos, and logos. These are harder things to teach. But we can try.

Some of the problem may lie in the tendency of literary-fiction writers to disregard what mass-market novels can teach us. These books are not always masterfully written, but—if the videos of readers weeping on BookTok are evidence—they are clearly tapping into human experience and making readers feel. A hell of a lot, apparently.

Consider Colleen Hoover, who self-published for years before readers drove her romance and young-adult novels to best-seller status. A lot of her books admittedly rely on “trauma narratives”—a critique that’s lately been wielded against some literary fiction as well. But readers keep reading her because they connect to her stories of women finding love while on the brink of financial collapse or seeking to break patterns of domestic violence. Say what you will about her sentences, but no Colleen Hoover fan thinks that ChatGPT can replace her.

To be fair, the best writing teachers were already pushing students to write with emotional honesty long before AI was breathing down their neck. The greatest lesson I ever got in the art of memoir was to write the story you felt, not a recounting of what was actually lived. A course in science fiction taught me that the complex emotions of humanity can sometimes best be conveyed outside the realm of reality. A novel workshop gave me the idea of the author as a maestro, conducting the reader through an emotional journey that should have many movements and variations.

And yet despite all of this, I’m not sure I actually believe that writing as art can be taught at all. One can certainly improve and gain greater mastery over the form. But the magic stuff that makes the great literary artists what they are cannot be manufactured and replicated. At least, not in a classroom. Only, possibly, out there in the wild world, by living and observing.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’m off to see a one-woman show.