A three-hour drive east from the bustling streets of Seoul, a checkpoint marks the beginning of a journey to one of the most heavily militarised borders in the world. The military police scrutinise personal identification against a pre-approved list before granting passage.

It is here, in Goseong county, in a restricted section alongside the demilitarised zone (DMZ) on the border with North Korea, that South Korea hopes to promote a literal path to peace.

The 3.6km Goseong route is one of a dozen DMZ peace trails, scattered along the border, that have been opened to tourists this year – Koreans only, for now – to encourage them to explore the idea of unity through hikes within restricted areas offering direct views into the secretive North.

The Korean war ended in July 1953 with an armistice but not a peace treaty, meaning the North and South are still theoretically at war.

On the Goseong route, an eerie calm prevails. The peaceful beach appears undisturbed. The guide shares tales of wildlife encounters, lending the surroundings the air of a leisurely Sunday walk. At one point, there’s even the chance to pat some puppies born from one of the dogs gifted by North Korean leader Kim Jong-un to former president Moon Jae-in.

Yet, there are signs that betray an underlying unease: a range featuring human-shaped practice targets, watchtowers scattered here and there, the military police escort. It is as if time stands still, a haunting relic of a terrible war frozen in its tracks.

“There are few countries in the world where people live like this, divided,” says local resident Um Taek-gyu, 86, who used to work as a fisherman on the east coast. “There’s more to this place than barbed wire.”

Um is in a position to know. He was displaced from his home town only kilometres away in what is now North Korea when the war broke out seven decades ago and Goseong county was split in two. He never imagined the border would become permanent.

‘I came to see a glimpse of the true essence of peace’

Hiker Kang Min-joo was inspired to join the DMZ Freedom and Peace Grand March, a special seven-day expedition along several of these trails, to understand the past, and its influence on the future. “I wanted to remember how precious and grateful I am for the freedom and peace I have. Many young people like me have become numb to the pain of division.”

Fellow walker Kim Hak-myeon said: “Watching the birds fly back and forth between North and South Korea without any barriers, I came to see a glimpse of the true essence of peace.”

Further along the route, at the Goseong unification observation tower, visitors find themselves at a place that stands as both a vantage point and a poignant reminder of division. It is the nearest viewing point to gaze out over the Mount Kumgang range in North Korea. The coastline leading towards it seems almost within arm’s reach.

Through binoculars, visitors can peer towards the North. On the left, a road winds its way to the facility where family reunions have taken place. The most recent was in 2018, bringing together 89 elderly people who had been separated from their family members for decades.

Just 40,000 of the 133,000 people registered as part of separated families are still alive. Every month, hundreds of them pass away.

Tours to the Mount Kumgang resort – a tourism destination on North Korean soil that was a rare symbol of inter-Korean collaboration – were once part of an inter-Korean agreement but were suspended in 2008 after the shooting of a South Korean tourist. They have never resumed.

Picture-perfect coastline, with no photography allowed

At the foot of the observation tower is a cage with two white Pungsan dogs, Haerang and Kumgang: the puppies born from one of the dogs given to former President Moon Jae-in by Kim Jong-un after their historic summit in 2018.

Downhill from there is the most dramatic part of the Goseong DMZ peace trail: a short trek alongside the heavily fortified beach.

A steep descent down a set of wooden stairs leads to the sand for a picturesque walk, with the beach nestled amid breathtaking natural beauty. Here, visitors can admire turquoise waters amid the vast expanse of the ocean. For security reasons, photography is strictly prohibited.

This area is, for the most part, off-limits to civilians. On one side, a barrier is adorned with signs warning of mines, and on the other, lies a barbed wire fence with sensors detecting movement that stretches along the sandy beach.

“Korean citizens need to be pre-approved to enter this area, and only 20 people can join each DMZ path on a daily basis,” says Kim Kyung-jin from the defence ministry, who oversees projects linked to the DMZ.

Foreign tourists cannot join these trips because it is a restricted area, he says, but the defence ministry and other government bodies are in talks to create a pilot programme next year that would allow foreigners on to selected trails.

After about half an hour’s walk, escorted by several military police at the front, middle, and rear, visitors reach the Southern Limit Line. Beyond this point lies the DMZ itself , controlled by the United Nations Command on the southern side of the border situated two kilometres to the north.

This place is not without its share of incidents. Just over two years ago, a man escaped North Korea by swimming several kilometres before coming ashore in Goseong. Another defector, reportedly a professional gymnast, managed to evade detection by leaping over two sets of fences.

‘I am still heartbroken’

Next stop is the DMZ museum, where wooden boats are on display, used by defectors to reach the south in a desperate attempt to seek freedom. On 24 October, a number of North Koreans arrived on a similar boat just south of Goseong. To date, South Korea has received about 34,000 defectors. While the number of arrivals in recent years has plummeted, mostly due to the pandemic and increased border restrictions, their numbers are back on the rise.

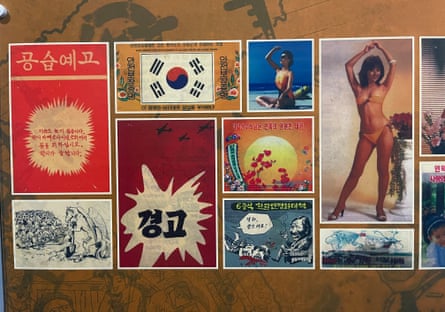

The museum also houses exhibits on the transformation of the DMZ into a sprawling ecological park, cannon shells fired from North Korea in 2010, as well as a collection of propaganda pamphlets that provides insight into the ideological tug-of-war between the two sides. North Korean leaflets promised a socialist nirvana, while those from the South tantalised the value of freedom through seductive imagery, including women in bikinis.

Beside the propaganda exhibit is a tree and mural decorated with hundreds of messages of hope and wishing reconciliation. One read, “Even if we cannot fully reunify, let’s live in peace.”

For Um Taek-gyu, separated from his relatives all those decades ago, that pain of separation is still raw.

“Having been separated from my family has given me a lot of sorrow all this time. Even though I’m now living well, I am still heartbroken and cry once a day,” he says, as he wipes tears away.