One of the Bravest Things a Book Can Do

Writers are uniquely able to uncover—and condemn—a country’s troubles: Your weekly guide to the best in books

Suggesting that literature has a singular higher purpose is ludicrous; it is and can do many things. But some of the bravest, most enduring pieces of writing are those that uncover, then challenge, a nation’s troubles. These works are, of course, most effective when the prose itself is great. In his essay on the Uyghur writer Perhat Tursun’s novel The Backstreets, Ed Park focuses on the book’s artfulness, rather than its politics. But he also comments on the “downright brutal[ity]” of the protagonist’s life—the mistreatment and the violence he faces—as a Uyghur man living in Ürümchi, the capital of China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Park imagines that the novel’s descriptions of racism against Uyghurs contributed to Tursun’s 16-year prison sentence.

Like Tursun, Orhan Pamuk has also faced retribution from the country he takes as his subject: Turkey. As Judith Shulevitz explains, Pamuk must contend with numerous “political and legal constraints” on his writing; he was charged with “denigrating Turkishness” after alluding to the Armenian genocide in an interview and is now under investigation for allegedly mocking Turkey’s first president in his most recent novel. He has also suffered threats and harassment, though bafflingly, it’s impossible to determine who exactly is behind these aggravations. Thus, they seep into his writing, creating a “literature of paranoia.” In the U.S., Jamil Jan Kochai has used surrealism to criticize the United States’ endless wars in the Middle East, showing “how inured we’ve become to the strangeness of war,” writes Omar El Akkad. And if a writer is around long enough, one might be able to trace the arc of a country’s history in their work. In his penultimate novel, John le Carré observed and bemoaned the fact that, in recent years, “money has displaced ideology as the primary battleground” in his native Britain.

Today, the historian and writer Andrea Wulf believes that challenges to our individual autonomy are chief among the troubling developments in America. In her recent book, she writes about the Jena Set, the group of German philosophers and poets who came together at the turn of the 19th century and “revolutionized the way we think of ourselves and the world.” Today, we are “empowered” by the “absolute importance they placed on personal freedom,” Wulf notes. “At a time when we find our democracies hollowed out and threatened by liars, despots, and reactionary politicians,” she writes, we must “fight for this legacy.”

Every Friday in the Books Briefing, we thread together Atlantic stories on books that share similar ideas. Know other book lovers who might like this guide? Forward them this email.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

What We’re Reading

Traffic in Ürümchi, Xinjiang’s capital, in 2018 (Carolyn Drake / Magnum)

Xinjiang has produced its James Joyce

“Persecuted by the religious right and its foe, the Chinese Communist Party, Tursun would be a heroic figure regardless of the quality of his output. It’s bittersweet for us Anglophones, then, that the slim evidence we have—136 pages, distilled over a quarter century—is close to a perfect work of art.”

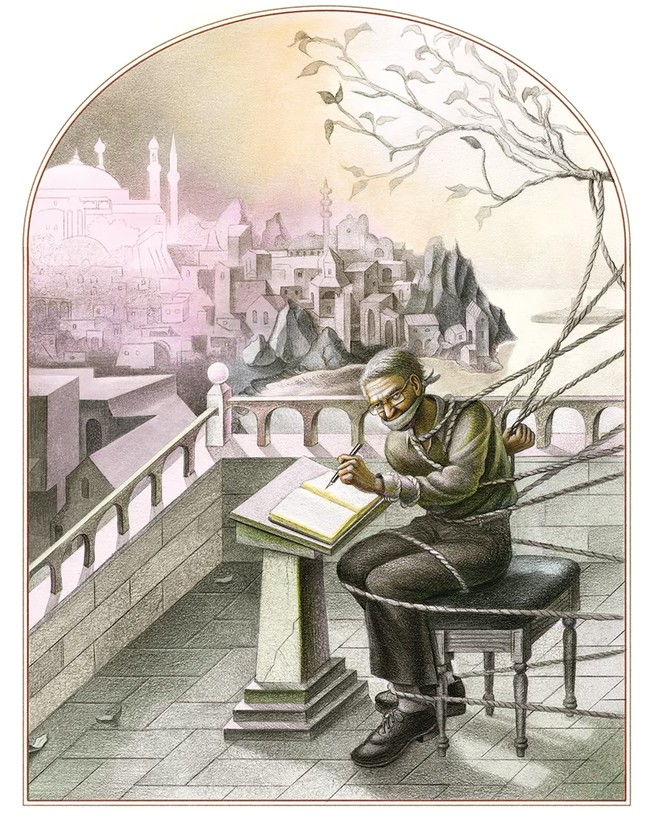

Armando Veve

Orhan Pamuk’s literature of paranoia

“When Pamuk called himself a paranoid writer, he named other masters of the genre—Dostoyevsky, Borges, Eco, Pynchon—and then said he had a certain edge over them, having grown up in a country that ‘has appropriated paranoia as a form of existence.’ He was referring to Turkey, of course, a nation of political chaos, military coups (four since Pamuk was born, in 1952), and frequent furor over anti-government plots.”

Library of Congress; Getty; Joanne Imperio / The Atlantic

The dark absurdity of American violence

“By using a fantastical style to describe the ordinary lives lost over the course of the war, Kochai brings into relief the farcical nature of a conflict in which an army can investigate itself for the death of phantom terrorists killed remotely from a control room. The result is a dark literary impeachment, a fable in which the emperor is missing not clothes but a conscience.”

David Levenson / Getty

John le Carré’s scathing tale of Brexit Britain

“In many ways, the intrigue of Agent Running in the Field is secondary to its function as a renowned author’s scathing indictment of a country selling itself out.”

Katie Martin / The Atlantic; Getty

Where our sense of self comes from

“Freedom brings with it both responsibilities and dangers. The friends in Jena struggled with that, just as we do today. From the moment this seismic shift toward an empowered self rippled out of Jena, people have had to deal with the perils.”

About us: This week’s newsletter is written by Maya Chung. The book she’s reading next is Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime, by Bruno Latour.

Comments, questions, typos? Reply to this email to reach the Books Briefing team.

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.