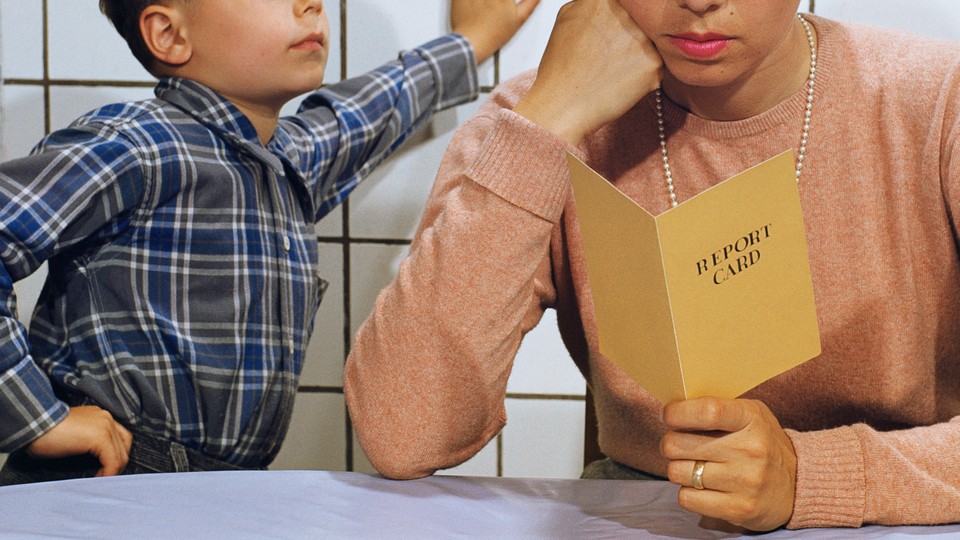

Parent diplomacy has always been a dicey endeavor for educators. The war stories teachers swap about nightmare parents are the stuff of legend. But in the decade since I started teaching in a public school outside of Boston—and particularly during the pandemic—strained conversations have become the norm. Expectations about how much teachers communicate with parents are changing, burnout is getting worse, and I’m worried about what this might mean for the profession.

More parent involvement is, on its face, a good thing. Research shows that kids whose parents stay involved in school tend to do better, both academically and socially. But when I hear from some parents all the time and I can’t reach others at all, students can start to suffer. As I’ve talked with colleagues and experts in the field, I’ve realized that this is a common problem, and it’s been intensifying.

Some communities are struggling with major teacher shortages. Half of those that remain in the profession say they’re thinking about quitting sooner than intended, according to a 2022 survey of National Education Association members working in public schools, and nearly all agree that burnout is a significant problem. In fact, a 2022 Gallup poll found that people working in K–12 education were more burned out than members of any other industry surveyed. Without enough teachers, instances of classroom overcrowding are popping up in public schools across the country.

Still, many parents (understandably) want to talk—seemingly more than ever before. According to a 2021 Education Week survey, more than 75 percent of educators said that “parent-school communication increased” because of COVID. Similarly, just under 80 percent of parents said that they became more interested in their kids’ education during the pandemic, a poll by the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools found. My school district has always encouraged teachers to get parents involved; it recently invested in translation services to make talking with caregivers easier. This past year, the district encouraged teachers to call at least three families a week and log the conversations in a school database.

Online grading systems, which became popular in the early 2000s, were supposed to facilitate parent-teacher communication. Some of my veteran colleagues complained that the new system was confusing, but I loved the simple accessibility. I used to make students have their parents sign failed tests and quizzes, but once more parents joined the online portal, I could send grade alerts directly to parents’ phones. Since then, these platforms have become nearly universal; only 6 percent of respondents to a 2022 Education Week survey said that their district didn’t use one. They’ve grown more advanced, too, letting me share written feedback on assignments, class-discussion notes, and updates on school policies. But although this has given parents a more comprehensive view of their child’s performance and made information more accessible, it has also introduced a new set of stressors for teachers. Whereas parents once had to either wait for official events or go through secretaries and principals to set up separate in-person conferences with teachers, they can now ping me with the click of a button. Though I’m glad the bar for asking questions is lower, I learned quickly not to post grades after I put my baby to bed, because when I did, within minutes, I’d receive emails from parents who wanted to discuss their kid’s grades—no matter how late it was.

These challenges can be even greater for private-school teachers, according to Cindy Chanin, the founder of a college-consulting and tutoring business, who has worked with hundreds of teachers and administrators in elite schools in Los Angeles and New York City. Some private-school parents are paying $50,000 a year (or more) for their child’s education. Because they’re spending so much, many tend to focus on the outcomes and want a greater say in elements as varied as whether their child gets extra time on a project and how a field trip is run, Chanin told me. She said the teachers she speaks with are completely overwhelmed.

Yet although finding time to wade through emails from parents can be hard, some teachers face a problem that can seem even more insurmountable: getting parents involved at all. Erica Fields, a researcher at the Education Development Center, told me that though it’s important not to generalize, research shows that sometimes “lower-income families view themselves as ‘educationally incompetent’ and [are] less likely to participate in their child’s learning or question a teacher’s judgment.” Some may also speak a different language, which can make any type of communication with teachers difficult—and that’s before you even get into the educational jargon. Indeed, on average, parents of students whose families fall below the poverty line or who don't speak English attend fewer school events.

In 2020, this all reached a breaking point for me. The loudest parents seemed focused on issues I couldn’t control, and the strained parents I had always struggled to reach had even more on their plate, during what was likely one of the biggest disruptions to their children’s educational career. When my district opted for remote-only schooling in the fall of 2020, some parents complained to me that we were acting against our governor’s advice and caving to “woke” culture. Tensions with certain parents escalated further after the global racial reckoning sparked by George Floyd’s murder. My students were eager to express their opinions, but as parents listened in on these virtual discussions, some told me that they didn’t think we needed to be talking about these topics at all. In other districts, the problems could at times be even more intense: According to a 2022 Rand Corporation report, 37 percent of teachers and 61 percent of principals said that they were harassed because of their school’s COVID-19 safety policies or for teaching about racial bias during the 2021–22 school year.

Despite how much I was hearing from these caregivers, I don’t think that the bulk of our conversations were actually helping students. Some of my parent-teacher conferences turned into debates about vaccines and police brutality—anything but a student’s academic performance. I wanted to work with these parents, but I didn’t know how to find common ground.

Meanwhile, I was even more uncertain about how to reach the parents of my most vulnerable students—many of whom I was really worried about. Though I knew that going back into an overcrowded building was unsafe, I also knew that many of my students were living in poverty. Some didn’t live with anyone who spoke English and couldn’t practice their language skills in between classes. A few didn’t have internet access and had to go to the local McDonald’s or Starbucks for free Wi-Fi to sign on to school. When I did get in contact with parents, I heard stories about being laid off and struggling to put food on the table. Other caregivers told me about family members who had died. When these families were dealing with so much, I felt silly bothering them about their child’s missing homework assignment.

I’d estimate that over the course of my career, I’ve spent at least five hours a week talking with or trying to reach parents. When I don’t feel like I’m helping students, I wonder if these conversations are worth having at all. Still, I do have discussions with parents that feel genuinely fruitful. During the pandemic, for example, I weighed the risks of in-person learning against the potential mental-health dangers of online schooling with caregivers who told me that they felt just as stuck as I did; the situation ahead of us might have been uncertain, but at least we knew that we would work through it together.

With parents and teachers both under so much strain, it’s clear to me that nitpicking over grades isn’t the most productive use of our time—and neither is fighting about COVID policies, which teachers don’t have the power to set. But we shouldn’t give up on these relationships altogether. They can easily go wrong, but when they go right, they help students not just survive, but thrive.