Prestige TV’s New Wave of Difficult Men

The small screen is offering up heroes who are resolutely alienated, driven to acts of violence that they don’t want to inflict and can’t enjoy.

The horror of Patricia Highsmith’s Tom Ripley, to me, isn’t that he’s a killer, or an aspirant, or even a literary version of the parasitic wasp that nests gruesomely inside the zombified form of its prey. Rather, it’s that he’s that most familiar of contemporary monsters: an incurable narcissist. At the beginning of the 1955 novel The Talented Mr. Ripley, as Ripley is moldering in poverty in New York and scraping together a living via petty mail scams, he’s sustained by an illogical faith in his own superiority. The “crummy bums” he socializes with aren’t really his friends; the grime in his borrowed tenement apartment is not his dirt. Ripley is pathetic, but we can’t escape him as readers, mired as the novel is in his interiority. We suffer the physical pain he feels when he’s forced to have conversations not focused on himself. We’re steeped in the envy, the self-pity, and the crippling status anxiety that drive him to murder. (It’s not all dark—at one point Ripley feels so pathetically validated when someone sends him a fruit basket that he breaks into sobs.)

Are we supposed to like Tom Ripley? I don’t think so. Nor are we supposed to hate him, nor even find him particularly evil. “Ripley isn’t so bad,” Highsmith once reportedly observed, for her part. “He only kills when he has to.” He’s a pragmatic villain more than a psychopath, although the consequence is that he’s rarely all that surprising. Anthony Minghella’s 1999 movie adaptation of the novel tried determinedly to humanize him, casting Matt Damon as an insecure sad sack who’s driven to a crime of desperate passion when he’s sent to Europe to bring home—and is promptly humiliated by—Jude Law’s wealthy, callous Dickie Greenleaf. The film’s visual splendor, with its bluest blue skies and sun-dappled Neapolitan coast, offered relief from Ripley’s claustrophobic mind and relentless grudgery; it also placed him in the long lineage of sympathetic American strivers who go just a tiny bit too far.

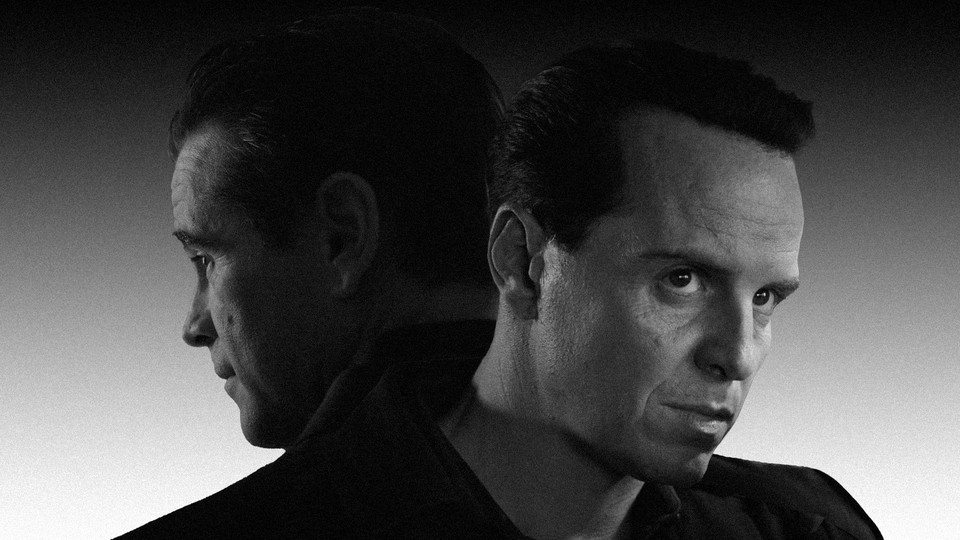

Ripley, a new eight-part adaptation on Netflix by the writer and director Steven Zaillian (Schindler’s List, The Night Of) is resolutely different, almost to the point of inversion. Shot in striking black and white—it’s the most beautiful series I’ve ever seen on the platform—it is emotionally spare, deliberate in its pacing, and morbidly funny. This Ripley, played with a malevolent flourish by Andrew Scott (Sherlock, All Of Us Strangers), is a void, an emptiness where the soul should be. The show’s lack of color turns it into a chiaroscuro meditation on light and dark, as Zaillian cuts moodily from Caravaggios to gargoyles to endless shots of staircases. What a piece of work is man! the series seems to sigh, encouraging us to mull the depths of human depravity, and the possibility art offers for ascension.

You could be forgiven, watching television lately, for wondering whether we’re in a new mini-era of Difficult Men, after a stretch defined by complicated female characters. Sullen, brooding heroes and antiheroes have returned to the small screen, paying homage to European New Wave and Old Hollywood alike. On Apple TV+’s Sugar, a different show with a vexing protagonist that leans heavily on dreamy cinematography and the innate brutality of life, a private detective played by Colin Farrell searches for a missing girl while clips of film-noir classics flash erratically through his head. Late last year, the most fun I had watching television was with Reacher, Amazon’s kinetic adaptation of the Lee Child potboiler series, starring Alan Ritchson as the phlegmatic, solicitous, intensely violent giant.

In his 2013 book, Difficult Men, a history of television’s second Golden Age and the troublesome characters who embodied it, the writer Brett Martin argues that “the most important shows of [that] era were … largely about manhood—in particular the contours of male power and the infinite varieties of male combat.” The current state of masculinity on TV, by contrast, is one of alienation. These shows are steeped in nostalgia and pay homage to bygone eras but offer up heroes who feel resolutely other, isolated and disconnected and driven to acts of baroque violence that they don’t want to inflict and can’t enjoy.

The decision to shoot Ripley in black and white works on multiple levels: It evokes the heft and visual symbolism of classic film while keeping pleasure manifestly at bay. We are in Ripley’s world, and something is missing. The lush florals and endless summer of Minghella’s film offered consolation for what the hero himself lacked, but Zaillian wants us to experience life the way Ripley does, as something cold and sharp. When he’s tasked in the first episode by the wealthy American shipbuilder Herbert Greenleaf to bring home his feckless son, who’s gallivanting off the proceeds of a trust fund, I half expected the show to bloom into color once Ripley landed in Europe, as if to signify the opening up of his gloomy world. Instead, things stay monochrome. His travels, his new friends and experiences, will not bring him any relief.

Ripley could be grimly ponderous—each episode runs close to an hour, and one is spent in intensely close quarters with the hero as he labors to get rid of a dead body. Strangely though, it’s not. There’s so much to look at on-screen, so much that draws the viewer’s eye, that the series is intensely absorbing, and the rhythm of the later episodes, whose dialogue is largely in Italian, feels almost musical. Ripley’s sense of humor is also a surprise. Dickie (played by Johnny Flynn) is a nonentity whose paintings are so bad that they bring to mind the botched “Monkey Christ”; Marge (Dakota Fanning), his American “friend”—sexuality is as ambiguous here as in Highsmith’s novel—is prim and self-serious, toiling diligently away at writing a very dull book. These are Bad Art Friends, which gives Ripley, a natural if untrained aesthete, the moral high ground. His murderous dedication to self-improvement isn’t wholly original (Constance Grady has labeled the genre he belongs to “striver gothic”), but he does, like Hannibal Lecter, appreciate beauty infinitely more than capital.

This latest Ripley has been interpreted as an antihero for the current moment, a scammer and confidence trickster who, in the present day, would surely have a gallery under investigation by the IRS and a hugely popular Instagram. (The 2023 movie Saltburn, which followed a working-class student drawn into the circle of an aristocratic friend, borrowed heavily from Highsmith, heaping on homoerotic melodrama, bodily taboos, and Millennial kitsch.) But Scott plays Ripley in a way that feels chilly to the touch—his grand ambitions and desires, if he has them, are hard to determine. When he first gets to Italy, we see him sweating and huffing his way up ancient cliffside stairs, recognizably vulnerable, without a grasp of the language or a clue how to behave. As the series progresses, though, he becomes as hard as flint. Scott’s eyes betray no emotion beyond boredom or malice: The more comfortable his Ripley gets, the more sinister he feels—and the more operatic as a character.

The performance doesn’t quite match the nuance of the show. On Sugar, it’s the other way around: Farrell is giving us something so poignantly human that it transcends the heightened, sometimes absurd plot points he has to navigate. The series, created by Mark Protosevich (I Am Legend, Thor), has been billed as “genre-bending,” spanning film noir, sci-fi, and Westerns, with some global gangster intrigue thrown into the mix. What it really is, though, is a surprisingly good crime drama with an awful lot of unnecessary adornment. John Sugar (Farrell) is an oddball private detective working for a clandestine agency; he abhors violence but is very good at deploying it, is an ardent cinephile, and cares deeply about vulnerable people and dogs. Watching it, I’d heard a twist was coming, which still didn’t quite prepare me for how erratically the show upends itself. It’s obvious that Sugar isn’t what he seems, and he appears to have based his personality whole cloth on gruff cinematic legends and Raymond Chandler novels. And yet he’s manifestly good—too good for this seedy realm.

In the first episode, Sugar is commissioned to find a missing girl, the granddaughter of a storied Hollywood film director, Jonathan Siegel (James Cromwell), and the former stepdaughter of a rock star, Melanie Mackintosh (Amy Ryan). The series uses a fair amount of voice-over, requiring Farrell to spout clichés as pat as “Sometimes a thing is just a thing that happened,” and “We all have our secrets. Even me. Especially me.” Sugar’s car (a vintage Corvette), his suits (“Savile Row”), and the specific affliction he has of seeing life crosscut with scenes from Humphrey Bogart films all suggest he’s nostalgic grist for Apple’s key dad demographic. So why couldn’t I stop watching?

Maybe because the performances are extremely good—Farrell, yes, and Ryan’s softening punk edges, as well as Eric Lange playing a terrifyingly charismatic criminal and Anna Gunn as a scheming mother. Sugar also looks extraordinary, casting Los Angeles in shades of coral and green without sanitizing its seamier side. The episodes, running about half an hour each, are tightly plotted, and the central mystery is an enticing one. (Not the one about Sugar himself, which will be better the less I acknowledge it.) Really, though, the detective himself is a lovely puzzle, more interesting for what he doesn’t say than for what his labored interior monologue spells out. What is a man? How can Sugar try to retain his humanity and integrity in a landscape of abjection? And the most difficult question of all: Are the stories we love the most actually serving us? This, to me, is what makes John Sugar so compelling: He loves the movies, and the lessons of light and dark that they impart. He’s just not always sure that he can trust them.