What follows is not news.

Earlier today, Elon Musk furthered the narrative that he wishes to engage in hand-to-hand combat with Mark Zuckerberg, tweeting in such a way as to suggest that he was at Zuckerberg’s front door. (Previously, he called Zuckerberg a “chicken.”) By typing these words, I am complicit in what has been a months-long bit of posturing over the ridiculous premise that the pair will fight in a “cage match.” If you’re hearing this all for the first time, I apologize profoundly.

My general framework for navigating modern life is to try to imagine, and then make sure to never bet against, the dumbest possible outcome. Thanks to our tech billionaires, it’s harder than ever to game out what that might mean. Would Musk and Zuckerberg sweatily groping each other among Etruscan ruins on pay-per-view constitute the dumbest possible outcome of this Silicon Valley promenade of fragile male egos? Surely, watching an off-balance Musk dislocate his pinky toe against the femur of the man who gave us the “Poke” button would constitute the teleological end point of the social-media age. You would think! But innovators innovate.

Anyhow, thanks to some screenshots shared by Musk, we know that the pair have been texting recently. “I don’t want to keep hyping something that will never happen,” a seemingly frustrated Zuckerberg said to Musk. Musk, meanwhile, appeared oblivious and continued to egg Zuckerberg on. At one point, as the result of an inexplicable series of firing neurons, Musk managed to not only type but also send the following two-sentence tone poem: “I will be in Palo Alto on Monday. Let’s fight in your Octagon.”

At a sentence level, these words, strung together in this order and seemingly without irony, are hilarious. From the standpoint of being a human, the Musk-Zuck cage match is an offensive waste of time—the result of a broken media system that allows those with influence and shamelessness to commandeer our collective attention at will. Musk and Zuckerberg have generated a pseudo event that bolsters their own relevance. Meanwhile, you and me? We’re hostages trapped in Mark Zuckerberg’s backyard octagon.

Ostensibly, we are conditioned to pay attention to Zuckerberg and Musk because they have a lot of money and power. They employ tens of thousands of people, and the decisions they make with their platforms have profound implications for how we communicate. There’s little doubt of their influence—just look at the way that Musk has managed to dominate the exosphere with his satellite-internet company. Logically, it tracks that people are interested in what these men do with their spare time, how they conduct themselves in public and private life. The erratic actions of billionaires are newsworthy. Right?

It’s not so simple. This episode shows the limitations of newsworthiness, which, as I’ve previously written, is a choice masquerading as an inevitability. Attention hijackers learned ages ago that newsworthiness affords them an opportunity to stay in the spotlight, provided that they keep doing outrageous things. This tactic, which has become so common as to feel unremarkable, fundamentally breaks what is now an extremely outdated supposition by the media, which is that the people they cover are doing things for reasons besides simply attracting attention and engagement. Schrödinger’s Cage Match is a sterling example of a pure attention spectacle. It’s good PR for Zuckerberg, who is in the news for something other than fomenting geopolitical unrest through Facebook. For Musk, a man who pursues attention the way a black hole hoovers interstellar gas and dust, every mention of his name—including in this article, no doubt—is better than silence.

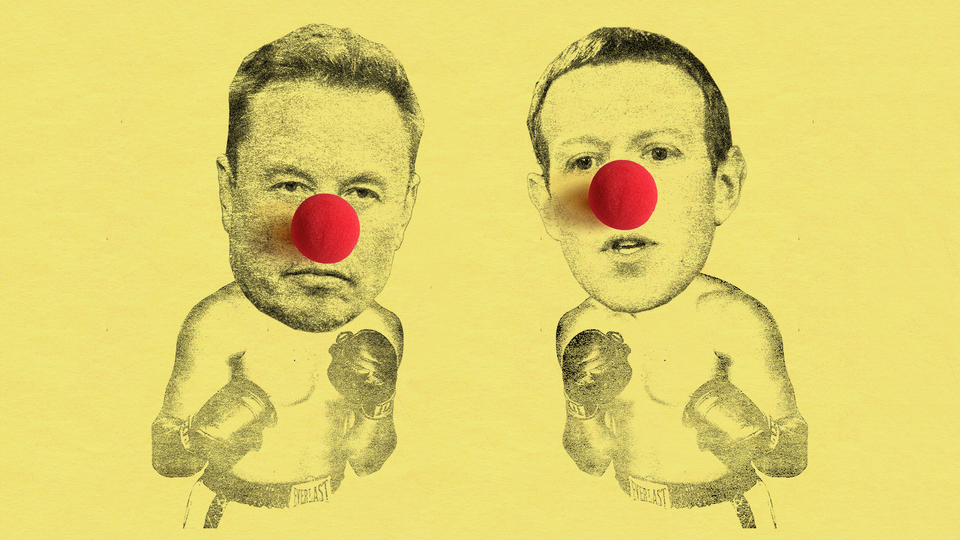

A few years ago, I used the phrase “boy king” to describe Zuckerberg, a reference to an early book about Facebook. After that piece was published, a Facebook executive privately messaged me to say that such language proved I was a biased writer uninterested in a fair examination of the company. I’ve been thinking about that message this summer: How is anyone to interpret the brawl-baiting and shirtless thirst traps, if not as the proclamations of attention-seeking man-children? And how can we direct our attention toward the tech industry’s projects when some of its biggest names are distracting us by cosplaying as Jake Paul? I’ve talked to countless Silicon Valley entrepreneurs and investors over the years who have complained about the “techlash,” the idea that the media has a reflexive pessimism about the technology industry and the people who run it, such that legitimate technological progress is hindered. The criticism implies that we ought to focus less on the personality and politics of the people doing the building and more on the work itself.

Musk and Zuckerberg ask that we take them seriously as titans of industry and men of importance. They demand our admiration and attention for their ideas and accomplishments much in the same way that their platforms demand our engagement. But in seeking our notice in such uniquely vapid, cynical ways, they forfeit it in others. Regardless of the reason, these are serious men who seem all too eager to show us that they are not serious men. Something needs to change. We (and, I should note, I’m speaking to myself here too) must hold two contradictory ideas in our heads. These men are important insofar as their consequential business decisions must be scrutinized and held to account. But their every utterance and eyeball emoji is not worthy of our attention. These men may be important, but they are not always worth our time.