Secrets and Lies in the School Cafeteria

A tale of missing money, heated lunchroom arguments, and flaxseed pizza crusts

This article was featured in One Story to Read Today, a newsletter in which our editors recommend a single must-read from The Atlantic, Monday through Friday. Sign up for it here.

Late on a fall afternoon, a skeleton crew staffed the cafeteria at New Canaan High School, in Connecticut. Custodial workers cleaned up the day’s remains while one of the cooks prepped for the evening’s athletic banquet.

A woman entered quietly through the back door, the one designated for deliveries and employees. She wore a jacket over a loose gown. She clutched something to her chest that appeared to be a bag connected to an IV.

“What are you doing here?” one of the workers asked.

The woman said nothing. She shuffled to her small office. The door clicked shut. The workers exchanged looks. They’d heard that Marie Wilson had been undergoing treatment for breast cancer. She had every right to stay home and rest. Yet here she was, hobbling into the kitchen near sunset, reporting for duty.

There would be more days like this one. Days when Wilson endured life’s worst moments—a grandson’s leukemia diagnosis, successive surgeries for a wrenched wrist, a foreclosure. On every one, without fanfare, she made an appearance in the cafeteria.

To some, Wilson’s unfailing attendance was an act of dedication, the fastidiousness of a woman charged with helping to feed some of the country’s wealthiest children. The job didn’t lend itself to missteps. This was New Canaan, a sylvan place of old-money mansions and modern farmhouses built with Wall Street bonuses. Standards were high—for the students, for the teachers, for the administration. The cafeterias were no exception.

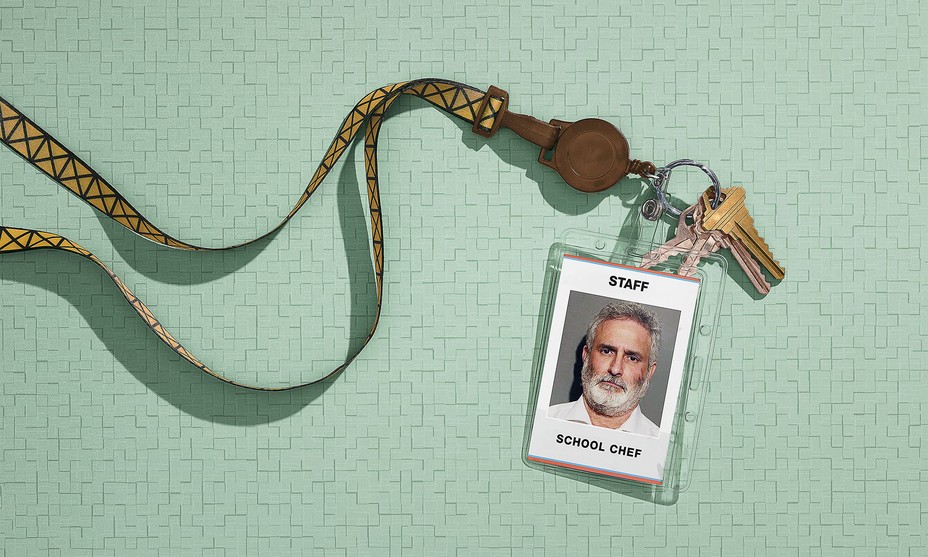

Headed by Bruce Gluck, a classically trained chef, the kitchens of the New Canaan public schools served farm-to-table fare before such a label existed. Gluck pushed his workers hard, demanding that they achieve his formidable vision. The workers were largely immigrant women, many of them Italians for whom English was a second language. Clashes inevitably arose, and when they did, Gluck turned to his second in command. Wilson knew how to talk to the women; she could explain what he wanted.

Wilson had grown up in neighboring Stamford; her father was an Italian immigrant and trash hauler whose everlasting advice to his children was that they surround themselves with respectable people. After a deli she owned shut down, Wilson got a job in a school cafeteria in New Canaan and moved into a modest house there. A year after Wilson was hired, her younger sister, Joann Pascarelli, got a cafeteria job there too. Together, they rose in the ranks, Wilson to assistant director of food services, and Pascarelli to manager of the middle school’s cafeteria.

For two decades, the sisters ran the cafeterias with an iron fist. Workers bore them grudging respect. But resentment bubbled too, and curiosity: Every year at Christmas, at the party Wilson hosted, the women stared in amazement at her house, and her Mercedes—unremarkable for New Canaan but stunning to workers who wondered how she could afford her lifestyle on a cafeteria salary.

The sisters clung to their hard-earned places, absorbing Gluck’s stormy criticism and serving as his enforcers. They gained Gluck’s trust, which gave them a degree of power magnified by the district’s faith in Gluck. The arrangement appeared to produce remarkable success: The New Canaan kitchens attracted national attention, upending the notion that school-cafeteria food was made only to be mocked. There was a sense that something special was being created, something best not meddled with.

The students of New CANAAN are the sons and daughters of hedge-fund principals and corporate executives who make their homes there, drawn by the town’s guarded seclusion. New Canaan sits at the end of a commuter-rail branch, latticed by stone walls and woods, fortified by strict zoning. The town is content to play the role of country squire to its splashier waterfront neighbors, Westport, Greenwich, and Darien. Continuity is prized; headlines are avoided.

When Wilson and Pascarelli first walked through the doors of New Canaan’s schools, in the late 1980s, the cafeterias served the institutional fare that is the bane of schoolchildren everywhere: fried this, fried that, droopy everything else. In a district where superlative was the norm, the cafeterias were outliers. Wilson herself wrote a letter to administrators threatening to quit over the quality of the food.

In 1994, the administration announced a new hire. Bruce Gluck had grown up in the Bronx and graduated from the Culinary Institute of America. He arrived with the passion of an evangelist. “Baby steps are great in certain situations,” he told Amy Kalafa, the author of Lunch Wars: How to Start a School Food Revolution and Win the Battle for Our Children’s Health. “But when it comes to the health of our children, you have to act now.”

Gluck preached the gospel of fresh food. His philosophy was “nature provides”—meaning food should be unprocessed, sourced from local sellers, seasonal, and organic when possible. He eliminated junk food from the cafeterias. Canned food went too. He successfully pushed the district to cut ties with the National School Lunch Program. The program boxed him into the Department of Agriculture food pyramid in return for subsidies the wealthy district didn’t need.

Free to roam, Gluck explored far-ranging culinary fields. Souvlaki, hummus, and quinoa tabbouleh appeared on menus. Pizza took the form of flaxseed crusts topped with freshly made sauce and mozzarella. “I roast the ducks the Chinese way, hanging in the oven,” he told Kalafa. “We develop our own recipes here. I use buffalo and ostrich, too.” Vegetables were the real deal: leafy greens, roasted squash. Old standbys slipped in if they could be converted usefully, like chicken fingers made with rice flour to become a gluten-free option. Desserts were low-sugar confections, yogurt parfaits and puddings made with block chocolate and fresh whipped cream.

For a time, Gluck considered excising the holy grail of school lunches: milk. He told Kalafa it was a myth that older kids needed milk the way babies did. He relented only after he found a hormone-free, grass-fed, minimally pasteurized option.

The overhaul met with bewilderment from some parents. But Gluck had his cheerleaders, moms and dads who advocated for the new offerings. More kids began buying meals. Higher revenue offset increased costs. “I don’t have to struggle to find the pennies to meet my budget,” Gluck boasted to consultants from the Greenwich school district who came inquiring.

It hardly mattered that there were no Michelin stars to be earned in the cafeterias. Gluck exhorted workers to bring him their ideas, to share in his passion. He wanted everyone on board, everyone working to create restaurant-quality food.

“I’ll look at something and say to the lead cook, ‘Let me ask you a question: Would you serve this at home?’ And if they even hesitate I say, ‘Throw it away. Why would you sell it here?’ And that’s what we’ve been pounding into their heads.”

But According to a federal lawsuit filed by one of the cafeteria workers, Gluck ran his kitchens with a petty tyranny that verged on caricature. He was a culinary artist, a Leonardo of the lunchroom, lashing workers for errors large and small. He would later laugh, recalling the time a worker attempted to serve cucumber gazpacho hot. But in the moment, mistakes rarely struck him as funny. He slammed doors, threw papers on the floor, pounded a wall, cursed, called workers “stupid” and “fucking bitch.” (Gluck denies all of these allegations. The lawsuit was settled for undisclosed terms.)

The workers were a tight group, and they tried warning one another when they saw his “ugly” eyes and beard coming. “He used to come in, don’t say good morning, not a smile … He used to look around like we were doing something wrong all the time,” one woman testified. “Like an animal. He used to walk in and then always mad.”

When food was not prepared to Gluck’s liking, another woman said, “the expression he have in the face, still today, I still have in my mind. Mean. Mean. Mean. Mean. He gets so red, so angry, you know, and then he threw the stuff on the floor and he run in the office.”

Tears were common. One woman, a diabetic, passed out after a meeting in his office. Another fell backwards into a chair as he barged toward her, screaming. Wilson heard the woman yell “Castigare!,” as if to say, “A pox on your children.” Yet another worker was so thrown by his rage when she tried to take home uneaten pizza that she wet herself.

But Wilson and Pascarelli didn’t shrink when Gluck barked. They didn’t cry when he vented. Between them, Wilson had the tougher exterior. Pascarelli was more yielding, and from a young age had followed the lead of her older sister. But there was a stoicism in both women, an ability to withstand Gluck’s outbursts.

With her office next to Gluck’s, Wilson endured his storming in and yelling loud enough for workers on the meat slicer to hear him. “I was a buffer, meaning if there was a complaint between him and a person, I would get the complaint and I would go fix it,” Wilson testified in a deposition for the lawsuit.

Her fixes, according to the workers, were punishments doled out with tiered precision: dish duty for first-time offenders, a school transfer for repeat offenders. After a worker fractured her neck in a car accident and missed a week and a half of work, Wilson assigned her dish duty. The worker handed in a doctor’s note saying she needed light work. But Wilson would not relent, and the worker assumed that seeking help from the union would be pointless: Pascarelli was the union president. Eventually, the woman quit. (Both Wilson and Gluck deny punishing workers and say there is no such thing as light work in a cafeteria.)

Wilson’s willingness to run interference for Gluck made her essential. He came to consider her a close friend, even as he bore down on her. She often said she was going to work for the school district until she retired. When there was trouble, it was either her job on the line or someone else’s—and it wasn’t going to be hers. Her stance was that of a woman who looked out for herself, as the Italian women saw it, her sternness a kind of hardness, like that of a man.

But phone calls from the New Canaan mothers undid her. Gluck himself disdained the mothers. “I don’t understand these fucking women in this town. They put their little tennis skirts [on] and they go and play,” he said, according to the testimony of Antonia Torcasio, who managed one of the elementary-school cafeterias. “And then they want me to worry about if the kids have to eat gluten-free or not gluten-free.”

So it was Wilson who listened to them.

“They are good for nothing but just spending their money,” Wilson would say after hanging up, Torcasio told me. “They are rich and lazy. They don’t know how to cook or do anything.” On and on she went, as though she’d found a place to put everything that Gluck dumped on her. (Gluck and Wilson deny saying these things.)

It took Amy KalafA multiple phone calls and some persistence to arrange an interview with Gluck. He was in high demand. His program was the envy of other districts. Food-services directors from across the country sought his advice. His cafeterias landed on best-of lists.

When Kalafa finally visited Gluck at the high school in November 2010, he was stunningly blunt—federal regulations were stupid, wellness committees worthless, Michelle Obama incremental.

Kalafa’s account was admiring; she described Gluck in her book as a passionate visionary, a curmudgeon in all the ways a changemaker has to be. Yet from atop the mountain, Gluck was struggling. The catering business he operated on the side shut down, and in 2012 he and his wife filed for bankruptcy. The paperwork paints a portrait of collapsed finances and unmet obligations: $140 in cash on hand, a negative balance in a checking account, 79¢ in a savings account, unpaid rent, and debt running pages and pages.

The sisters were in turmoil too. Their brother alleged that while their mother, Alba, was battling cancer, Pascarelli and Wilson were siphoning money from properties she owned. The fight grew ugly; one night in 2001, the brother rammed Wilson’s Mercedes with his dump truck. Both sisters denied stealing from Alba, but she cut them out of her will before she died in 2002.

Pascarelli opened credit card after credit card. In 2010, she declared bankruptcy on debts of more than $900,000. She says her husband was ill and they had racked up medical bills. Still, a neighbor told me that, years later, so many UPS trucks made deliveries to her house, she assumed Pascarelli ran an Etsy shop.

Meanwhile, Wilson took her brother to court in a property dispute over her New Canaan home. The case dragged on for eight years before they bitterly settled in 2012, with Wilson agreeing to pay him money she believed she didn’t owe.

A reigning presumption in New Canaan was that the town finances were well in order. Such was the prerogative of a place home to so many of the nation’s leading financiers. For nearly two decades, outside auditors had validated that view, issuing annual reports that gave the town a clean bill of financial health.

In 2012, however, the town decided a fresh look was needed. A new auditing firm came on board and delivered a rude surprise. The firm found numerous problems with the town’s practices, from sloppy record keeping to a lack of checks and balances. Taken together, the problems meant New Canaan was wide open for fraud.

“You have every right to be nervous,” the auditor told residents during a presentation, according to the New Canaan Advertiser.

An outcry went up. The town’s deep bench of financial talent clamored to help. The town convened a committee staffed with not one but two former CEOs of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu, the accounting giant. But even with such high-powered expertise, bringing the town into compliance proved challenging. After a year of work, the committee scolded the school board for ignoring its recommendations. In a letter, the committee members announced that they would suspend their work, citing a lack of “cooperation, trust and transparency between the Board of Education and the Town.”

The district charged its newly hired director of finance and operations, Jo-Ann Keating, with fixing what the auditors had flagged. She zeroed in on the obvious—the cafeterias.

School cafeterias can be financial briar patches. They are businesses unto themselves, taking in large sums in chaotic conditions. So tricky is cafeteria oversight that many schools outsource it. New Canaan had gone another route. It kept both food preparation and financial management in-house and tasked the food-services director with oversight of both. Its cafeterias raked in some $2 million a year, most of it through prepaid accounts, but about 5 percent arriving as cash.

Keating concluded that the cafeterias’ cash-handling procedures were lax, and she mandated new, tighter rules. At the start of the 2016–17 school year, the district also installed software on all cash registers that provided end-of-day cash tallies for each machine to Keating but not to cashiers. In Keating’s words, the system was a good, clean check—she could tell if a register’s tally differed from the amount reported to be in the drawer at day’s end.

Soon after, Keating started noticing problems at the high school.

Antonia Torcasio fit a familiar profile in the kitchens—a daughter of Italy, she grew up working in its fields, immigrated in 1970, became a homemaker, and, when her children were grown, took a job in New Canaan. She would claim in court that she was a frequent object of Gluck’s ire. She would get her revenge.

According to Torcasio’s version of events, in October 2013, Wilson called her into Gluck’s office, where he accused her of complaining to the school principal about her workload. He warned her not to speak with administrators, teachers, or staff. Then he turned to Wilson and said, “You deal with her.” Wilson said she was going to transfer Torcasio to a different school. (Wilson and Gluck dispute Torcasio’s account of the meeting.)

Years earlier, Torcasio would have let the incident go. But her daughter had become a human-resources manager, and told her mother she had options. Torcasio filed two lawsuits. One was against Wilson, claiming that she had put her hands on Torcasio’s shoulder after the meeting with Gluck and shoved her. A jury found in Wilson’s favor. Torcasio also filed a federal lawsuit against Gluck, the town of New Canaan, and the school board alleging that Gluck had created a hostile work environment and discriminated against female workers.

The town stood behind Gluck. “A sense of ‘How dare you go up against us?’ permeated the whole thing,” Richard Pate, Torcasio’s attorney, told me. He recalled district officials being united in their defense of Gluck. “Everyone praised this guy. Everyone thought he was incredible.”

But a federal judge ruled in March 2017 that the suit could go forward, citing evidence showing that “Gluck mistreated many or all of his employees” and “laughed and boasted about making employees cry.” (The school-board chair declined to comment for this article.)

The parties settled the case for undisclosed terms. Gluck stepped down at the end of the school year and moved to Vermont.

Wilson should have been a natural candidate to succeed Gluck; she’d been his deputy for more than 20 years. But about a month before the start of the 2017–18 school year, the district passed her over and hired an outside candidate. The new director was told to keep an eye on cash handling in the cafeterias.

In November, the new food-services director alerted Keating to an argument between employees at the middle school. It had escalated quickly, faster than it should have, as if there were something more at root. Keating decided to pay a visit.

Pascarelli, the manager, was under a great deal of stress outside of work. Her husband had filed for divorce and would later accuse her of changing the locks on their home while he was in the hospital for heart-transplant surgery; renting out the home without his permission; and clearing out their bank account, leaving him with $46. (Pascarelli’s attorney declined to comment on these allegations.)

Keating, during her visit, handed out her business card and invited workers to contact her if they wanted to talk privately. Less than a week later, at 7 p.m., she received an email from a worker. They met the next day, and Keating listened as the woman shared her complaints. Of particular interest to Keating were her concerns about cash handling.

Sergeant Kevin Casey was a 23-year veteran of the New Canaan Police Department. Before joining the force, he’d been a correctional officer at Rikers Island, in New York City. Now his office was a repository of some 1,600 pages of documents related to missing cafeteria money.

District officials had contacted police after Keating met with the middle-school employee and further investigation revealed what she called “significant trends.” By then, both sisters had been put on leave. In early December, Wilson resigned. Ten days later, Pascarelli did too.

One afternoon in February 2018, a cafeteria worker arrived at police headquarters for an interview with Casey and another detective. The worker was nervous, reluctant to talk. But the detectives reassured her that they already knew what was happening at the school, according to an affidavit.

Tentatively, the worker began. She said she had seen things at the middle-school cafeteria that she thought were weird. Like Pascarelli telling her that when students paid with cash she was not to enter the amounts into her register. And Pascarelli removing large bills from her register between lunch periods. And, at the end of the day, Pascarelli taking her register drawer and forcing her to sign a deposit slip showing a cash amount far lower than what she knew she’d taken in.

It appeared that things might change after the district installed the new software and a representative from the software company trained workers on the new system. He showed them how to count their drawers at the end of the day, sign a deposit slip, and put the cash into a bank bag. But when he was gone, she said, Pascarelli told the workers to continue using the old method of not entering cash into the system. She said it took too long. She also kept counting workers’ drawers herself and filling out the deposit slips. Bank bags never arrived, the employee said.

Over the next few weeks, worker after worker sat for police interviews. They came from the middle school and the high school. Their accounts were remarkably consistent, with employees accusing Wilson of essentially the same cash-handling practices allegedly used by Pascarelli. (Wilson and Pascarelli both deny mishandling cash. The school district declined to comment on an ongoing criminal investigation.)

The district tallied its losses. Nearly half a million dollars had gone missing from the middle- and high-school cafeterias over the previous five years. That was as far back as the statute of limitations—and the investigation—went. If the sisters were indeed responsible, there was no telling how much they’d taken. They’d been working in the cafeterias for some 30 years.

Wilson wasn’t sleeping. In April, she showed up unannounced at police headquarters. Casey had already questioned her and Pascarelli, and both had steadfastly denied knowledge of any wrongdoing. But now here she was, telling Casey she was exhausted. She lay awake at night worried that he would arrest her. According to an affidavit describing the encounter, Casey asked if she wanted to get something off her chest. She said she did.

Seated in the interview room, Wilson wasted no time. Bruce Gluck was the culprit, she said. Starting in 2006, he’d insisted she give him $100 every day out of the cash collected from the registers. She said if she didn’t give it to him, he would search her desk to find it. Gluck’s daily demand continued until he left. Wilson began to cry. She shouldn’t have helped him, she said, but she’d been afraid of him and didn’t want to lose her job. So she gave him the money.

Six weeks later, Wilson returned for a third interview. Casey said her explanation didn’t add up, according to his affidavit. If Gluck had been taking $100, that still left money unaccounted for. Was it possible that Gluck had taken $100 a day, and she and Pascarelli also had each taken $100?

Wilson remained adamant: Gluck took the money. All she’d ever done was put up with her mercurial boss. But her denials didn’t settle the matter. In August 2018, the sisters were charged with larceny.

Soon after, a woman contacted the New Canaan police. She said she’d observed the high-school cafeteria up close back in 2000, when the medical facility where she worked was undergoing remodeling and its staff shared use of the high-school kitchen. In Marie Wilson’s office she’d seen desk drawers filled with cash, she told police. The money was loose, like someone had dumped bags of cash into the drawers. She also said she’d seen Gluck, who was still operating his catering business at the time, pull his Volvo up to the loading dock and fill it with cases of food from the school. (Gluck says he was moving the food to another school, making room for the medical-facility workers.)

On a November morning in 2018, Wilson and Pascarelli sat side by side in a crowded courtroom for a hearing in their criminal case.

News of their arrests had shocked New Canaan. Parents thought perhaps the alleged cafeteria thieves had covered up the stolen cash by double-charging students’ electronic accounts, and they bombarded school-board members with calls demanding to know whether they’d been fleeced.

I approached the sisters while they waited for the judge. Wilson was stiff and contained, her strict gray bob shielding her face and her purse strap kept squarely on her shoulder. Pascarelli was nervously chatty and seemed stunned as she glanced around the courtroom, eyeing the sea of other criminal defendants. She told me she didn’t think any money had gone missing. What had actually happened was that the new food-services director had taken a dislike to her. “[She] had an attitude and decided to get rid of people,” she said. Or perhaps it was the kids’ fault. They caused so much confusion, Pascarelli said. They used one another’s PINs to run up charges on their electronic cards and parents were always aghast, saying, “Not my child!”

The sisters had taken pride in their work. Now they were the object of ridicule in New Canaan. A few weeks earlier, nine boys at the high school had donned hairnets and white aprons over prison-orange jumpsuits with cash taped on them. A local paper featured a photo of the smiling boys with a headline announcing, “Exclusive: New Canaan ‘Lunch Ladies’ Seen at High School.” The caption called the gag “a little parody.”

Whatever had happened with the money, both sisters agreed, Gluck should have known about it. And where was he?

Investigators, it turned out, were wondering the same thing. In the spring of 2018, Casey had tried to track him down. They had scheduled an interview for mid-March, but Gluck had canceled a few days beforehand. In May, Gluck’s lawyer emailed detectives to say that Gluck would not consent to an interview about the missing money. His stonewalling left police with only Wilson’s claim that Gluck was the thief.

But then search warrants unearthed Gluck’s bank records, showing that he’d made suspicious cash deposits from 2012 to 2017—more frequent in the school year and dropping off in the summer, according to a report cited in an affidavit. They totaled nearly $40,000. Investigators could identify no legitimate source of income for the money. (Gluck says his wife had other sources of income.)

In April 2019, police arrested Gluck for larceny and conspiracy to commit larceny. The criminal cases are now chugging through the court system in Stamford. All three defendants have pleaded not guilty. By email, Gluck’s lawyer said that his client had no involvement in misappropriating funds from the school district and looks forward to clearing his name in court.

When I visited Gluck’s Vermont home hoping to speak with him, his wife ordered me off the property, following me across the yard and yelling, “Fuck off!”

The alleged thefts perplexed New Canaan—the notion that so much money could go missing with no one noticing. New Canaan is not a community used to being taken. Yet somehow, the town presented the opportunity and people seized it.

“It’s curious there were no systems in place,” one parent told me through the rolled-down window of her Land Rover as she waited for her daughter outside the high school. When I pressed her for her feelings about the alleged thefts, she demurred: “It’s a topic.” Then her daughter climbed in and she had to go.

In the cafeterias, Gluck’s buffalo and roasted duck are gone, replaced by standard fare such as cheese pizza, mac and cheese, and paninis. At the middle school, lunch one day in June was a hot dog.

The cafeteria workers remain on edge, fearful that they, too, might be accused of stealing. School officials told them not to talk to reporters. Those who did speak with me, though, said they’re glad the jig is finally up. Anyone paying attention knew something was wrong. For years, they’d talked among themselves. But they’d been too afraid to report their suspicions. They had no hard evidence, only observations.

“Your grandson almost die and you don’t take a day off?” Torcasio said. She paused, then added, “Because maybe she wanted to do her money.”

This article appears in the September 2019 print edition with the headline “The Lunch Ladies of New Canaan.”