The Georgia men wake everyone in the drenched dark. The pain of the march simmers through me, and I wipe at my mud-soaked clothing, swipe at the threads of soil in my wounds—all of it futile. We are tired. Even though the Georgia men threaten and harass and whip, we chained and roped women plod. “Aza,” I say, sounding the name of the spirit who wore lightning: “Aza.” Every step jolts up my leg, my spine, my head. Every step, another beat of her name: Aza.

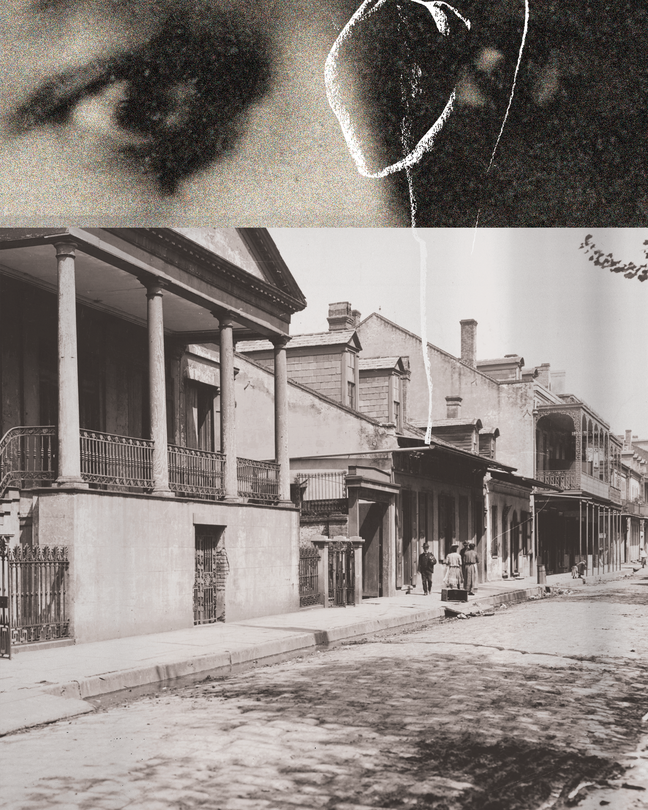

We walk down into New Orleans, and each step is a little falling. We leave the lake and the stilted houses behind; the trees reach, swaying and nodding on all sides, and us in the middle of a green hand. When the hand opens, there is a river, a river so wide the people on the other side are small as rabbits, half-frozen in their feed in the midmorning light. Aza disappears. The boat that carries us over this river is big enough that all the women fit. There is no reprieve from our rope here. This river is wordless, old groans coming from its depths. After we cross, there are more houses, one story, narrow and long, and then two stories, clustered close together, sometimes side to side, barely space for a person to stand between them. The grandest are laced with wrought iron and broad balconies: great stone palaces rising up and blotting out the sky. Long, dark canals cut the city at every turn. The air smells of burning coffee and shit.

People crowd the streets. White men wearing floppy hats coax horses down rutted roads turned to shell-lined avenues. White women with their heads covered usher children below awnings and through tall, ornate doorways. And everywhere, us stolen. Some in rope and chains. Some walking in clusters together, sacks on their backs or on their heads. Some stand in lines at the edge of the road, all dressed in the same rough clothing: long, dark dresses and white aprons, and dark suits and hats for the men, but I know they are bound by the white men, accented with gold and guns, who watch them. I know they are bound by the way they stand all in a row, not talking to one another, fresh cuts marking their hands and necks. I know they are bound by the way they wear their sorrow, by the way they look over an invisible horizon into their ruin.

But some brown people look like they ain’t stolen. Some of the women cover their hair in patterned, shimmering head wraps, and they walk through the world as if every step they take is their own. They are fair as I am, some of them even fairer, as milk-hued and blue-veined as the white women in their bonnets and hats. I slide close to Phyllis, lean away from the caravan of wagons rumbling past. A handful of women snake by; their head wraps are bright and glittering as jewels, and they look everywhere but at our bound line: stooped, bleeding, and raw from the long walk.

“They’re free,” I tell her.

“Who?” Phyllis asks.

“Them.” I point with my chin.

Phyllis sneezes and wipes her nose on her arm.

Three boys, heads shaved, follow behind an olive-skinned woman in a cream head wrap. The boys stare at us, their eyes wide and wondering, and the woman, who must be their mother, grabs the closest by his shoulder and herds the boys in front of her.

“Non,” the woman says. She hurries them to a trot that matches the horses pulling the wagons. “Allons-y.” One of the boys trips, but she bears him up with her hand on the back of his collar.

Phyllis watches them until they disappear around a tree-lined bend. I try not to, but I still search for more head wraps, more quick walkers with averted eyes who wear deep, brilliant colors. More who are free.

“Move,” the Georgia Man says, shouting us deeper into this warren of a city until he stops outside a wooden fence high as two women standing on each other’s shoulders. Haphazard roofs, tiled and patched, show over the top. There is a gate at the center of the fence, and as it swings wide, the sound of someone wailing in the enclosure swoops outward.

“In,” says the Georgia Man.

We walk in a knot through the door. I look back at the two-story houses and stone businesses. A white man with a bushy mustache stands on the porch of a home, his hands shoved in his pockets, watching us being herded. His face as blank as the windows.

“In, girl,” the Georgia Man says. The man across the street rubs one hand down his black-vested chest and tips his hat. The gate closes, ill-fitting wood scraping, and we are inside.

We enter into a courtyard clustered with buildings: Two are tall and whitewashed brick. The rest are short and windowless, their bricks dark as the river. The ground beneath us is beaten to dirt and sand, nearly as even as a wooden floor. But there are footprints in it, so many footprints: the dimples of five toes, the smooth ball of heels, sometimes ringed by the mark of a horse’s hooves. The Georgia Man enters one of the tall buildings, and his men dismount their horses and lead them to a stable. Laughter echoes from inside the buildings. Dogs yip and bark at the noise.

“Come,” says one of his men, short and burnt red at the forehead. His hair snakes below his collar. We women follow to one of the long, low, dark-brick buildings, while a white man leads the chained men to another building—this shack’s twin. We women stoop to enter, and when I stand, my hair brushes the ceiling. The taller women stoop and shuffle into the close darkness. There are no windows, and the only light comes from cracks between the bricks. The man takes his time untying us; the first woman he unbinds limps to the farthest corner of the room and sits. One woman drops to her knees right as the rope is taken off. Another hunched woman holds her hands in front of her like she has an offering, listing side to side. Phyllis slides down the closest wall. When my length of rope falls, I step backwards, slowly, as I did with my bees on days when it took time for the smoking moss to calm them. For a moment, the longing for my hive feels so strong, it makes me stumble to remember: the clearing, the old char of the tree, the honey, amber and heavy.

“Annis,” Phyllis says.

The Georgia Man closes the door. I sink to the floor next to Phyllis, lean my head back against the brick, close my eyes, and try to recall how beekeeping taught me to hold myself still, my mirth muted. How once, in my breathing, there was joy.

We sleep hungry, wrapped in rags. Phyllis’s rasping breath has turned to a hard, hacking cough. Some of the women snore, but most of them are still and silent as fallen trees. Snakes of smoke coil on the ceiling, and I wonder if this is where my mama came, if she slept on this floor too. If she laid in the close, hot darkness and thought of me. I scratch my scalp and imagine the press of my fingers as my mama’s the last time she washed my hair, oiled it, and braided it. I scoot so that my back grazes Phyllis’s, and for one minute, I let myself pretend she’s my mama, warm and whole.

A tendril of smoke winds through the crack of the bricks, gathers to sooty coils under the seam of the roof. Aza takes shape in a darker black.

“You came back,” I say.

“Others called.”

“Did you follow my mama here? To a pen?” I whisper.

Lightning rings Aza’s neck before sizzling to darkness. She does not descend to the floor.

“Yes.”

“What happened to her?” I ask.

The lightning arcs across her head in an electric halo. She frowns before speaking.

“The same that will happen to you,” Aza says. Her face changes. A softening around her eyes could be sympathy, but then it is gone, fast as the zip of a flitting hummingbird over her cheek. “You will sorrow. One will come and take you away.”

“You know?” I ask. “You know where my mama went?” Hope foams up my throat, and I do my best to swallow it all, the feeling, the hope, down.

“Out of this place,” Aza says. “She was taken away, north and inland.”

The feeling, the hope, is a heavy cream now, and it sinks down to my stomach.

“Did you follow her?” I ask.

Aza finally descends in a blanketing mist.

“She was ill, but she wouldn’t call me.” I reach out a finger. At the edge of Aza’s smoky garments is a pepper of cool rain. Her face is placid, still water. “Spirits need calling,” Aza says. “That’s the last I saw of her.”

I ball my hand into a fist and rub it against my stomach: It aches with cold.

“You knew she needed you,” I say, and wish I hadn’t. My hope gone rancid, bubbling up to eat at the back of my tongue like acid.

What I don’t say: You did nothing.

Aza is sharp and beautiful in the darkness. She looks away from me, beyond the brick walls, and her profile, for one perfect moment, is my mother’s. She seems near, near in the night, and longing clangs through me.

“Yes,” Aza says. “Sleep.”

I turn to my side, wondering how cold can soothe one moment and sear the next.

They make us wash in a trough before they dress us in sack dresses, all the same color brown. They take the first woman away midmorning while we are crouching in the low, dark building. When the first woman returns, she stumbles into the room before slinking into a corner. She refuses to speak, even when the other women crowd her, asking after her. Men come to the door and take us away, one at a time, calling us by name: Sara, Marie, Elizabeth, Aliya, Annis.

When the white man, featureless in the blotted-out doorway, calls me, I follow him into the bright, hot day. The slave pen is dusty and barren, but over the gate that separates us from the outside, the treetops lining the street sway. Clouds, with the underbellies of doves, float in the sky. The horses roped to poles shuffle and neigh. Men’s voices tangle into one rope, loop around me, squeeze. I can’t breathe. The white man leads me through the door of the grand building that the Georgia Man entered yesterday, but the Georgia Man is gone. There is a fireplace and a mantel inside, candlesticks to light the room, glowing before mirrors edged in gold. There is a desk, a table with ornate scrolling at the corners, and high-backed wooden chairs. There are five white men, clean-clothed, their hair smashed flat in indents left by the hats they’ve hung at the door. They are white-whiskered, tall and short, paunchy and lean, pale. They wear watch fobs. Their teeth gleam in the candlelight.

“Come here, girl,” says the shortest and paunchiest of them. He is red at the edges: his hands, his hairline, his cheeks all mottled red, as if he has slashed some animal’s throat and been splashed with blood. Another white man, lean and bald, stands next to him.

“Good gait,” the short man says. “Bright eyes.”

“She looks healthy enough, given you feed her,” says the lean man to his paperwork.

“As I will,” the short man says.

The lean man scribbles and talks over his shoulder.

“Take her in.”

“Yes, sir,” a voice says, and it is only then that I notice the brown woman, her hair covered and wrapped, her eyes on the floor, who stands from her seat and walks toward us, her shirt and skirt loose and plain. She puts out her hand to me but doesn’t take mine, and she turns, expecting me to follow her, before disappearing through a small door. The men are all watching me, but they say nothing. Inside, there is a low table with a stained cloth on it. I don’t want to go anywhere near it, but she points and says, “Please, sit.” I perch on the edge so the wood cuts into my legs.

“That’s the doctor, and he’s going to examine you. Ensure you’re healthy, and if something wrong, he’ll treat it.” She talks, but she looks beyond me, as if there is another me behind me, floating midair, ascending through the ceiling. Aza, I think. Aza, you said you would stay.

“You understand? Nod if you understand.”

I look at her, right at her: the splash of freckles across her high forehead, the mole at the side of her nose, the crooked set of her canine teeth.

“You understand,” she says.

Aza, I think. This woman free. Who spare her?

The doctor walks in.

“Undress,” the woman says.

Aza, look, I think. Look at her.

I pull my sack dress over my head. I swallow a small sound when the air touches my skin with a chill hand.

Aza. There is a shimmering at the side of my eye.

“He’s a doctor,” the woman says. She glances toward me and her eyes stick for a moment, and then she looks away. Shame like a frown on her. “He’ll … examine you,” she whispers, and she looks past her folded hands and down to her feet.

Aza, I think. Please.

The waxy string bean of a doctor walks in and measures: height, hands, feet, waist, legs, arms, and head. He looks in my open mouth, my ears, peers into my eyes. I jump when he palms my skull, presses down onto the plates of my head, rubs across my closed eyes. I keep them shut when his hand works its way from my crown to my neck and crawls downward, a walnut-knuckled, pale spider.

“Delicate features from some admixture. She shows no marks from childbearing. Slender waist,” the doctor murmurs. “And wide hips.” The head-wrapped woman scribbles his notes, her gaze fixed to the page. “Would probably sell best as a fancy girl,” he says. I imagine myself like Aza, floating above the head-wrapped woman, above the doctor, above the little worms of pain burrowing into me with the doctor’s fingers as he works them over me, into me, into sleeves and pockets ever more tender, even softer. But knowing that my mama endured this, and worse, snaps me back, back into my body. For all the fighting she knew, she prized, she could not rebuke this.

Oh, Mama.

One of the men leads me back to the low brick building. It is hot and close, and I want to warn Phyllis before she follows the same man back out, tell her of the woman, the thin doctor, his stabbing hands. But I can’t. I sit next to her and hug myself, every part of me wet: my head, my face, down the middle of my shoulder blades, my stomach, my wrists, between my legs where the doctor probed, and down to my red, open feet. I lean into the wall. I squint against the sharp threads of daylight coming in at the seams; there are etchings in the brick. Some letters. A shape that looks like a sun. And further down, a straight long line with a little triangle across the top. I touch it, trace it; it looks like a spear. I wonder if my mother might have carved this, put her mark here since she could never write her name.

I wonder if she left this for me.

When Phyllis returns, she tilts to a fall next to me. Her sobs, soft as they are, come out of her like pulled teeth. I wait for her to still, and then I take the ivory awl from my hair, from where it is hidden in my scalp, from where I have worn it every day since my mother was taken, and I scrape into the wall next to the mark that could be my mother’s. I scratch a circle, draw a straight line down the center of it, and then draw a little oval on one side of the circle, and on the other side, another: wings. When I squint, it could be a bee.

We are awake when the next white man comes to the squat building, unlocks the door, and directs us into the courtyard, where he lines us up before the seller, the short blotchy man laden with gold over his big-knuckled hands. The doctor stands off to the side with the woman who looks like us. Phyllis, next to me, crosses her arms over her stomach, as if she could protect her soft parts, those parts not bound by bone. The woman at the end of the line is short, shorter than most of us but muscled where the rest of us are thin as ribbon. The seller stands in front of the first woman and reaches out, grabbing her face.

“You a full hand. If a buyer asks, you say, ‘Yes, sir.’ ”

The doctor writes.

“Don’t, and you’ll be lashed. Understand?”

The woman trembles, shivering like a horse run too long. Then she nods. The seller moves down the line, studies each woman’s arms, fingers, legs, and back before speaking. “You a lady’s maid,” he tells a woman with one drooping eye. “You a prime hand,” he tells the big woman. “You a sick nurse,” he tells another who lurches with a limp. “You a child’s nurse,” he tells another with knotted hair falling down her back. “You a cook,” he tells the one whom the walk didn’t pare to nothing. “You a seamstress,” he tells Phyllis. She doesn’t even nod; her chin falls into her chest.

“And you …” He brushes one knuckle up my arm. “You don’t speak,” he says. “The buyers’ll know.”

He echoes the doctor, telling me that I am a fancy girl, my only worth between my legs.

A finger of fog curls over his head, encircles it, and grows fat. Aza rises from it. She shines in the sun: river water lit from above. Her arms hang loosely from her sides, and her mouth moves.

“See,” Aza says, and points to the seller’s back, where there is a flame, narrow as a candle, in the air. The thief moves to the next woman, speaks to her, but his words are muffled. The flame blooms to a fire. A molten head rises from it, then shoulders, then a torso, then a blazing gown. The face turns dark, and a nose appears, then a mouth, and then eyes. The spirit’s hair is a conflagration. Her head and shoulders crackle with definition, her visage a log fire, banked and blackened. Hovering over the man, over all of us, is a smoldering cloud of a woman, a burning spirit.

“See,” Aza says. “She Who Remembers.”

The seller steps to the next woman in our sad line and tells her how she will be sold.

The blazing spirit flexes her arms, which have turned black as her face. The seams in the wood of her forearms curl and move, form lines, form script. The fire at her heart slides into words. These words flow up her arms, over the hills of her shoulders, and into the valley of her black, black mouth.

“She is the witness to your suffering, to all suffering,” Aza says. “She witnesses and remembers. That is her power.”

The other spirit crackles and spits embers as the accounting scrolls up her arms, over her face, her whole body, only to disappear and make way for more as the women of our line nod at their narratives.

“This world makes us all anew. Calls new spirits, feeds the old. Gives us followers, offerings,” Aza says. “Us a piece,” she says.

I clench my hands, as if I could choke the seller’s words back into his mouth, back down his throat. I look over the other women in the line, past Aza, to the spirit who remembers. She looks back, her gaping mouth swallowing the last word, and smoke rises from her. There, the smell of an old fire, an ancient fire, a fire prodded and fed and blazed and stoked for generations. I wish I could speak; I want to ask Aza: What she going to do with it? What her remembering going to do? Aza’s fog obscures her hands, her arms, her gown, her neck, until all of her is wreathed, and with a crack, she disappears. She Who Remembers looks down at me, and her legs disintegrate, then her hips, her torso, her arms, and last, her face, all of it raining ash.

I would bury the awl in this short man’s eye.

This story was adapted from Jesmyn Ward’s novel, Let Us Descend, published in October 2023. It appears in the November 2023 print edition with the headline “She Who Remembers.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.