So Maybe Facebook Didn’t Ruin Politics

Large-scale experiments on social media, run behind the scenes during the 2020 election, suggest there is no simple fix for American democracy.

“DEMOCRACY INTERCEPTED,” reads the headline of a new special package in the journal Science. “Did platform feeds sow the seeds of deep divisions during the 2020 US presidential election?” Big question. (Scary question!) The surprising answer, according to a group of studies out today in Science and Nature, two of the world’s most prestigious research journals, turns out to be something like: “Probably not, or not in any short-term way, but one can never really know for sure.”

There’s no question that the American political landscape is polarized, and that it has become much more so in the past few decades. It seems both logical and obvious that the internet has played some role in this—conspiracy theories and bad information spread far more easily today than they did before social media, and we’re not yet three years out from an insurrection that was partly planned using Facebook-created tools. The anecdotal evidence speaks volumes. But the best science that we have right now conveys a somewhat different message.

Three new papers in Science and one in Nature are the first products of a rare, intense collaboration between Meta, the company behind Facebook and Instagram, and academic scientists. As part of a 2020-election research project, led by Talia Stroud, a professor at the University of Texas at Austin, and Joshua Tucker, a professor at NYU, teams of investigators were given substantial access to Facebook and Instagram user data, and allowed to perform experiments that required direct manipulation of the feeds of tens of thousands of consenting users. Meta did not compensate its academic partners, nor did it have final say over the studies’ methods, analysis, or conclusions. The company did, however, set certain boundaries on partners’ data access in order to maintain user privacy. It also paid for the research itself, and has given research funding to some of the academics (including lead authors) in the past. Meta employees are among the papers’ co-authors.

This dynamic is, by nature, fraught: Meta, an immensely powerful company that has long been criticized for pulling at the seams of American democracy—and for shutting out external researchers—is now backing research that suggests, Hey, maybe social media’s effects are not so bad. At the same time, the project has provided a unique window into actual behavior on two of the biggest social platforms, and it appears to come with legitimate vetting. The University of Wisconsin at Madison journalism professor Michael Wagner served as an independent observer of the collaboration, and his assessment is included in the special issue of Science: “I conclude that the team conducted rigorous, carefully checked, transparent, ethical, and path-breaking studies,” he wrote, but added that this independence had been achieved only via corporate dispensation.

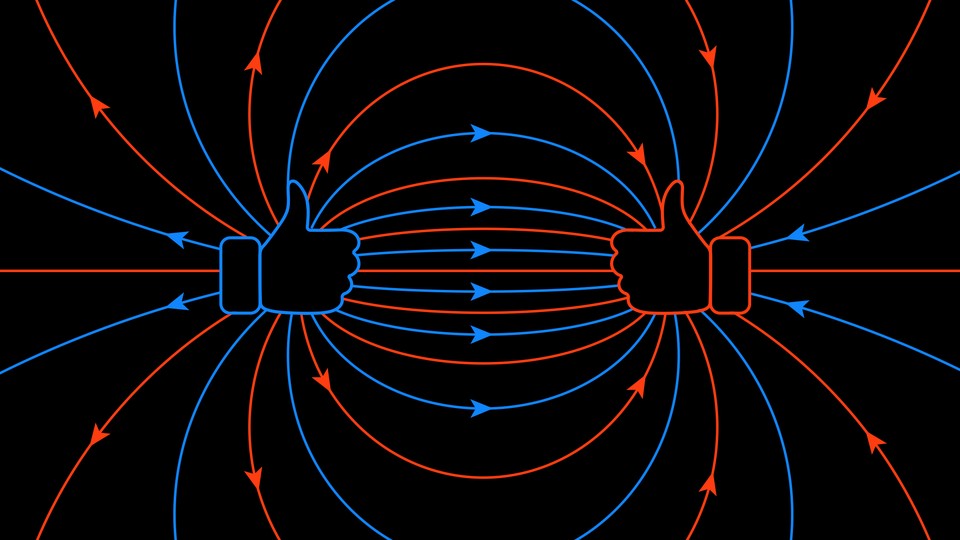

The newly published studies are interesting individually, but make the most sense when read together. First, a study led by Sandra González-Bailón, a communications professor at the University of Pennsylvania, establishes the existence of echo chambers on social media. Though previous studies using web-browsing data found that most people have fairly balanced information diets overall, that appears not to be the case for every online milieu. “Facebook, as a social and informational setting, is substantially segregated ideologically,” González-Bailón’s team concludes, and news items that are rated “false” by fact-checkers tend to cluster in the network’s “homogeneously conservative corner.” So the platform’s echo chambers may be real, with misinformation weighing more heavily on one side of the political spectrum. But what effects does that have on users’ politics?

In the other three papers, researchers were able to study—via randomized experiments conducted in real time, during a truculent election season—the extent to which that information environment made divisions worse. They also tested whether some prominent theories of how to fix social media—by cutting down on viral content, for example—would make any difference. The study published in Nature, led by Brendan Nyhan, a government professor at Dartmouth, tried another approach: For their experiment, Nyhan and his team dramatically reduced the amount of content from “like-minded sources” that people saw on Facebook over three months during and just after the 2020 election cycle. From late September through December, the researchers “downranked” content on the feeds of roughly 7,000 consenting users if it came from any source—friend, group, or page—that was predicted to share a user’s political beliefs. The intervention didn’t work. The echo chambers did become somewhat less intense, but affected users’ politics remained unchanged, as measured in follow-up surveys. Participants in the experiment ended up no less extreme in their ideological beliefs, and no less polarized in their attitudes toward Democrats and Republicans, than those in a control group.

The two other experimental studies, published in Science, reached similar conclusions. Both were led by Andrew Guess, an assistant professor of politics and public affairs at Princeton, and both were also based on data gathered from that three-month stretch running from late September into December 2020. In one experiment, Guess’s team attempted to remove all posts that had been reshared by friends, groups, or pages from a large set of Facebook users’ feeds, to test the idea that doing so might mitigate the harmful effects of virality. (Because of some technical limitations, a small number of reshared posts remained.) The intervention succeeded in reducing people’s exposure to political news, and it lowered their engagement on the site overall—but once again, the news-feed tweak did nothing to reduce users’ level of political polarization or change their political attitudes.

The second experiment from Guess and colleagues was equally blunt: It selectively turned off the ranking algorithm for the feeds of certain Facebook and Instagram users and instead presented posts in chronological order. That change led users to spend less time on the platforms overall, and to engage less frequently with posts. Still, the chronological users ended up being no different from controls in terms of political polarization. Turning off the platforms’ algorithms for a three-month stretch did nothing to temper their beliefs.

In other words, all three interventions failed, on average, to pull users back from ideological extremes. Meanwhile, they had a host of other effects. “These on-platform experiments, arguably what they show is that prominent, relatively straightforward fixes that have been proposed—they come with unintended consequences,” Guess told me. Some of those are counterintuitive. Guess pointed to the experiment in removing reshared posts as one example. This reduced the number of news posts that people saw from untrustworthy sources—and also the number of news posts they saw from trustworthy ones. In fact, the researchers found that affected users experienced a 62 percent decrease in exposure to mainstream news outlets, and showed signs of worse performance on a quiz about recent news events.

So that was novel. But the gist of the four-study narrative—that online echo chambers are significant, but may not be sufficient to explain offline political strife—should not be unfamiliar. “From my perspective as a researcher in the field, there were probably fewer surprising findings than there will be for the general public,” Josh Pasek, an associate professor at the University of Michigan who wasn’t involved in the studies, told me. “The echo-chamber story is an incredible media narrative and it makes cognitive sense,” but it isn’t likely to explain much of the variation in what people actually believe. That position once seemed more contrarian than it does today. “Our results are consistent with a lot of research in political science,” Guess said. “You don’t find large effects of people’s information environments on things like attitudes or opinions or self-reported political participation.”

Algorithms are powerful, but people are too. In the experiment by Nyhan’s group, which reduced the amount of like-minded content that showed up in users’ feeds, subjects still sought out content that they agreed with. In fact, they ended up being even more likely to engage with preaching-to-the-choir posts they did see than those in the control group. “It’s important to remember that people aren’t only passive recipients of the information that algorithms provide to them,” Nyhan, who also co-authored a literature review titled “Avoiding the Echo Chamber About Echo Chambers” in 2018, told me. We all make choices about whom and what to follow, he added. Those choices may be influenced by recommendations from the platforms, but they’re still ours.

The researchers will surely get some pushback on this point and others, particularly given their close working relationship with Facebook and a slate of findings that could be read as letting the social-media giant off the hook. (Even if social-media echo chambers do not distort the political landscape as much as people have suspected, Meta has still struggled to control misinformation on its platforms. It’s concerning that, as González-Bailón’s paper points out, the news story viewed the most times on Facebook during the study period was titled “Military Ballots Found in the Trash in Pennsylvania—Most Were Trump Votes.”) In a blog post about the studies, also published today, Facebook’s head of global affairs, Nick Clegg, strikes a triumphant tone, celebrating the “growing body of research showing there is little evidence that social media causes harmful ‘affective’ polarization or has any meaningful impact on key political attitudes, beliefs or behaviors.” Though the researchers have acknowledged this uncomfortable situation, there’s no getting around the fact that their studies could have been in jeopardy had Meta decided to rescind its cooperation.

Philipp Lorenz-Spreen, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development, in Berlin, who was not involved in the studies, acknowledges that the setup isn’t “ideal for truly independent research,” but he told me that he is “fully convinced that this is a great effort. I’m sure those studies are the best we currently have in what we can say about the U.S. population on social media during the U.S. election.”

That’s big, but it’s also, all things considered, quite small. The studies cover just three months of a very specific time in the recent history of American politics. Three months is a substantial window for this kind of experiment—Lorenz-Speen called it “impressively long”—but it seems insignificant in the context of swirling historical forces. If social-media algorithms didn’t do that much to polarize voters during that one specific interval at the end of 2020, they may still have deepened the rift in American politics in the run-up to the 2016 election, and in the years before and after that.

David Garcia, a data-science professor at the University of Konstanz, in Germany, also contributed an essay in Nature; he concludes that the experiments, as significant as they are, “do not rule out the possibility that news-feed algorithms contributed to rising polarization.” The experiments were performed on individuals, while polarization is, as Garcia put it to me in an email, “a collective phenomenon.” To fully acquit algorithms of any role in the increase in polarization in the United States and other countries would be a much harder task, he said—“if even possible.”