Society Tells Me to Celebrate My Disability. What If I Don’t Want To?

On living with cerebral palsy

Listen to this article

Listen to more stories on audm

My memory of the moment, almost a decade ago, is indelible: the sight of a swimmer’s back, both sides equal—each as good and righteous as the other. An ordinary thing, and something I had never had, and still don’t have. To think of that moment is to feel torn—once again—about how I should respond to my condition: whether to own it, which would be the brave response, as well as the proper one, in many people’s eyes; or to regret it, even try to conceal it, which is my natural response.

I have a form of cerebral palsy called hemiplegia, which affects one side of the body. The word has two parts: hemi, meaning “half,” and plegia, connoting stroke or paralysis. I have had a “half stroke,” but I prefer the romance of my high-school Greek teacher’s translation: I was, as he put it, struck on one side. Plus, it’s a more accurate description of what happened to me. At birth, the forceps used to pull me out of the womb pierced my baby-soft skull and damaged my cerebral motor cortex. On my left temple is a tiny scar left by the forceps and shaped, rather unfortunately, I’ve always thought, like an upside-down cross—the anti-Christ symbol.

I look, I’m told, basically normal. I am not in a wheelchair. I have good control of my limbs. I write and I paint. I can do most everyday tasks. Although my symptoms are typical—muscular tightness, limited movement ability, poor muscle development—they are mild. For this reason, everyone calls me lucky. And it’s true—compared with other kids in the waiting room of the cerebral-palsy ward, I was lucky, extremely lucky. But still, I never asked to be in that waiting room. I did not look like those kids inside the hospital—would balk at being classed with them, even—but my body didn’t fit in outside the hospital either. Doctors, friends, parents—a platoon of people who have never experienced what I have—commend me on my normalness. This always makes me feel accomplished, until I realize that what they really mean is: Normal, considering …

When I was a child, my symptoms were more pronounced than they are now. I simplified my deformities: I had a Good Side and a Bad Side, even telling kids at primary school that half my penis didn’t work (I had to have some fun). My Good Side, my left, was my superhero; I was actually right-handed, but taught myself to use the superhero side. My Bad Side, my right, was a cave-dwelling creature, a Caliban, a spindly, weak, shameful thing that I’d hit with my left hand when I was angry. I used to scream at my mother, crying, You did this. You gave birth to this.

I had a noticeable limp. My right heel couldn’t get to the floor, which left me on perpetual tiptoe. Unless my foot was strapped into a splint, my ankle couldn’t reach 90 degrees—the doctors’ acid test of normality. I needed shoes of two different sizes to allow for the added width of my daytime splint. My mother would explain the situation to shop assistants as I sat on the little sofa waiting for my mismatched shoes to arrive. Their faces turned to pity, or something like disgust. Did they think I was contagious? My nighttime splint had no give whatsoever. When I’d get up to pee in the night, waddling along in the strange walk that the splint forced on me, I’d pass my bathroom mirror and stare. Despite the crocodile pattern the nurse had let me choose, it all looked so medical, so unnatural—so, well, disabled. And I would think, I am not this.

As if to make it official, my doctor said, “You do not have motor skills.” I’ve never been able to move just one finger on my right hand, for example. If one finger is moving, they’re all dancing some uncoordinated dance. I needed help in class. I found it tricky to cut and paste, to organize myself, or to write for long periods of time, because my hand would cramp. It was humiliating enough to have a personal classroom assistant, but the assistant, Yulia, also had to massage my foot each morning to relax my muscles. She wasn’t popular with the other kids at school. Her foreign accent, tough manner, and short haircut made her a prime target for crude, all-boys-school-style ridicule. I often found it easier to join in than to defend her. I wanted everyone to think I didn’t need her. She never cared about the other kids being rude. But if she overheard me, she’d look at me with eyes that made it clear I was betraying her.

I would meet her in the black box of my primary-school drama studio half an hour before classes began. I’d take off my shoe, splint, and sock. She’d squeeze Johnson’s Baby Oil onto her hands and then take my foot roughly—kneading and pushing and pulling it. I would apologize again and again in my head. I’m sorry you have to do this. I’m sorry I’m like this.

Sometimes another kid would walk in. My body would revolt in panic—I’d squirm away from Yulia, desperately ashamed of the vision of my naked foot and ankle, moist with oil, poking out of my trouser leg. Something haunted me about the fleshy color of my skin with nowhere to hide in that black, black room. I’d pull my sock back on as quickly as humanly possible and sit there, staring at the floor, until Yulia firmly asked him to leave. When he’d gone, she’d reach an arm out, indicating that I should take my sock off once more.

At age 12, I beat my lifelong best friend—a boy I’d been in diapers with—in a tennis match at his grandfather’s house. He didn’t like losing, and he screamed from the baseline, “You disabled cunt.” I ran inside. In the kitchen, sobbing, I bumped into his grandfather and his mother—incidentally, my mother’s best friend—who asked what was wrong. I began to tell her, a woman I’d known all my life, a woman who’d known about my disability before I could even speak, and she lifted a finger in the air and said, “Ah. Don’t mention names. No one likes snitches.” I turned to his grandfather, hopeful, but he simply said, “No one said that to you, Emil.” I expected kids to be nasty, but had thought adults grew out of it.

As I prepared to leave primary school, I was also preparing for an operation on my Achilles tendon, which would mitigate my limp. The operation was scheduled for the final day of the school year, and so while every other boy in my class piled into a bus headed for a theme park to go on rides with names like Stealth and Nemesis Inferno, I was driven to a hospital in the suburbs of London. My mother spent the day reminding me that I’d never liked roller coasters anyway. I was given a wheelchair until I could walk again, but after one day of being eyed by strangers, I opted for crutches. I longed to hold a sign that read THIS CHAIR IS TEMPORARY. I AM LIKE YOU. My cast eventually came off, my heel now reached the ground, and my strange, clodhopping gait was gone.

I moved on to secondary school. No more splints, no more personal assistants, no more massages, no more limp. My parents assured me: Normal starts now. But that was not true. I was hit with a new regime—a twice-daily therapy program of swimming, stretching, and working with weights.

Each morning, I arrived in the funky-smelling changing room of my all-boys school sometime between 7:15 and 7:30. I found a space on the bench and a corresponding peg that wasn’t already littered with the chucked-off black-and-maroon ties, white shirts, trousers, sports bags, and boxers of the swim squad, which got there before me. In order to minimize my time spent naked, I was already wearing my regulation Speedo trunks under my uniform. I took off my own tie, shirt, and trousers and dumped them in my black-and-blue Sports Direct bag, which I carefully hung up.

Looking down at my nearly naked body, I longed for a different one. Something about puberty had made me fat, like a baby: My stomach ballooned out so that I could only just find the tips of my toes beyond it. My Good Side looked exactly that—good. But my Bad Side remained a perpetual disappointment. The swimming was meant to mitigate the effects of my disability, but swimming was the last thing I wanted to do.

The changing room connected directly to the pool, and the stench of chlorine was unavoidable. With nowhere else to go in this windowless part of the gym complex, it found your nose and clogged it. From my seat in the changing room, I could hear the swim squad, which had already been training for 40 minutes—the reverberating splashes, the critical shouts, the coach’s whistle. Their sonic booms stretched up past the viewing gallery to the ceiling and crashed back down again, echoing off the water.

I made my way through the corridor to the pool, holding my arms around my tummy. A mass of indistinguishable squad muscle—here a lean leg, there a powerful arm, there a goggled head on a bull-muscled neck—filled four of the pool’s five lanes. I approached the fifth—the teachers’ lane—and reluctantly lowered myself in. This was the only place where the school and swim coach could think to put me. My elderly French teacher was usually in there already, breast-stroking at the same pace his lessons went. Of everyone in this pool, it was his team I was somehow put on.

Even underwater, I attempted to cover my wibbling fat, knowing that the squad’s goggles allowed for plain viewing of my body. As I went up and down the pool, doing my customary half-swim, half-walk, their thoughts consumed me. Did they know why I was in their pool? Had their coach told them? Did they care? Scarier still, were they so passionate about their sport that they didn’t even notice me?

After swimming, they filed back into the changing room. They were teammates: not exactly friends, but they shared a closeness. They laughed about races won and lost. They stretched out, leaned over, bent down. Like ancient Greeks in the gymnasium, they had bodies that were a total luxury. I showered in my trunks after them, then hurried to a private cubicle to change into my underwear, all the time careful to avoid the mirrors that lined the walls. I covered my body with towels, hands, arms, anything at all so that no one, myself included, could see it in its entirety.

When one of the swimmers was dressed and ready to leave, the others shouted a goodbye and nodded, lifting their head and their eyebrows together in a way that encompassed the entirety of masculine prowess. But not once in all the years I changed with them did any of the swimmers look my way.

Well, there was one time, actually. Marcus was a boy, two or three years ahead of me, whom everyone either knew or knew of. He was, as far as I could tell, everything anyone could ever want to be. We never spoke—why on earth would we?—but so powerful was his physical presence that I became acutely aware of my lumbering body if he so much as walked past me in the school corridor. He seemed to be taller than anyone else in his year, although that probably wasn’t the case. He was always greeting people, stretching out an arm and a hand for some über-cool, effortless handshake.

The incident occurred when I was 15 or 16. I came out of the pool late, and only Marcus and a friend of his were still getting changed. By this point, my body had morphed slightly. I still felt overweight and cumbersome, and my disability still left half of my body lacking, but the past three years of training had at least made me look more like others my age. After showering, I went back to my bag and began getting dressed.

Marcus was in his underwear with his back facing me. I don’t know quite what happened that day, but some deep-set mixture of jealousy, longing, and desire prevented me from looking away. His back was the mightiest thing I’d ever seen. Everywhere you looked it was packed with muscles. And the symmetry! He turned and Achilles was standing there in the locker room. I traced every contour, every ebb of his body, with my eyes, inventorying every part of him that I was not.

I came to, and realized that both Marcus and his friend were standing there, watching me staring at him. There were codes, and I, a locker-room weirdo, had just broken them.

“Dude,” said the friend to Marcus, cutting the silence with a cruel splutter of laughter, “I think someone likes what he sees.”

Marcus started laughing and mock-provocatively tensed his body in my direction. “You want a piece of me, Sands?”

And while I did a double take—had he just said my name?—I understood how far away from these boys I was. How, if I answered his question honestly, the truth would be out: No, I don’t want a piece of you. I want all of you. I want to have what you have.

I said nothing. I backed away into a bathroom stall. I didn’t come out again until they had left.

I stopped swimming a few months after this, defying my parents, my school, and the medical committee that oversaw my rehabilitation. I had developed psychosomatic symptoms that made it unfeasible for me to carry on. At around the same time in the morning as I would start my swim, I would begin to hear a chorus of voices in my head. They screamed at me in a dark gibberish. Although it wasn’t English, I knew what they were telling me: I was worthless, useless. I would stop mid-stroke and hold my hands to my ears, trying to make them stop. At first, I thought the water had made my ears go funny. But the voices grew louder, darker, and more overwhelming. There were more hospital appointments. More concerned doctors. A specialist wondered if we knew the word schizophrenia.

When I stopped swimming, the voices stopped too, suggesting that the episodes were a result of some severe anxiety connected with the pool. As a deal, I swapped my five swims a week for more time in the gym and more stretching. I preferred this. For one, I could be clothed. But more than that, I could work toward goals that were less about competition and more about personal growth: getting big arms or a six-pack, having a meal plan based on eating lots of proteins. Things that most boys my age wanted.

As I understand now, my disability pushed me harder. Closed doors draw attention to open ones. When I was in my early teens, I competed for my school’s annual reading prize: First place went to the student who was best at delivering a poem or short story aloud. I got through the heats easily. Backstage, at the final, I watched as others nervously ambled about, familiarizing themselves with the Keats or Kipling poems that their parents had perhaps helped them pick out for this round. One by one, they were called up, until eventually it was my turn. I took to the podium. I opened my book. I began with the first line of the first chapter: “In Which We Are Introduced to Winnie-the-Pooh and Some Bees, and the Stories Begin.” It is the chapter with the line “Then he climbed a little further … and a little further … and then just a little further.”

And I won. It didn’t bother me at all that no one else was particularly interested in winning this made-up prize. What mattered to me was that I’d won it on my own, reading something I loved, words of my choosing. I remember feeling at the time, as silly as it sounds, that somehow, by reading a children’s book when everyone else was pretending to be an adult, I’d beaten the system. What system that was, I still don’t know—this was just a diction competition for adolescents at a private school. But I held the feeling close.

There were few physical activities I actually could not attempt, but many I could not do well. I am thinking, in particular, of football—soccer. I tried to play when I was very young. Had I persevered, the necessity of using both legs would have proved helpful in rehabilitating my right side. But a concrete block descended if a ball was ever brought out at a friend’s house or while on holiday. If a stray ball came off someone’s foot in a park and I was expected to kick it back, I froze. I could not play. I did not play. I refused to play.

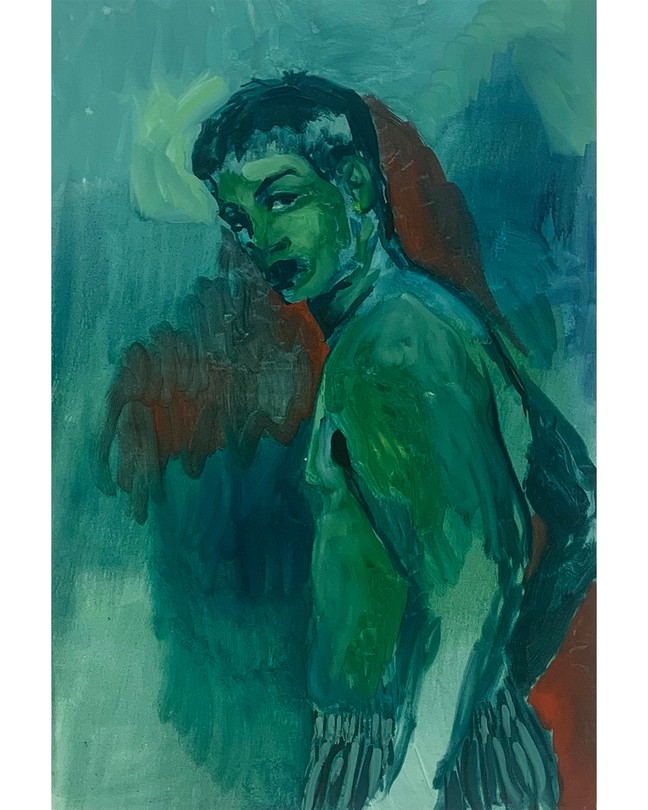

There was a power in saying no, but saying no also left me out. Every day at school, a lunchtime soccer game stretched across the fields outside. I took a different door—I began to go to the empty art studios. The studios were adjacent to the fields, and from my easel, I could see the game. Muffled shouts came my way. At a certain point, however, I began to look forward to my solitary lunchtime activity. The prospect of making new work and concentrating on something that mattered to me felt important. I started to think about going to art school and used the extra hour a day to create a portfolio.

As we reached the final year or two of school, the studios began to fill up a little. Two younger boys began editing their street photography in the computer suite. An art teacher inspired a group of classmates to come in every day and try screen printing. Although my school was only for boys in the earlier grades, it was coed in the final two years, and girls and boys could work in the studios together. My friend Sarah often sat across from me, drawing tiny floral patterns that, by the end of lunch, had ballooned out to fill the page. In the studios, on busy days, you couldn’t hear the game outside at all.

Today, hardly anyone knows I am disabled. I tell no one, because I believe people will like me less. Maybe just for a split second. Maybe for longer. Or maybe I should rephrase: I believe people will like me more if they think I am like them. So I go out of my way to keep my disability private. When I am tired, a residue of my old limp returns. On the few, but truly excruciating, days that someone notices and asks if I have hurt my leg, I lie and say I twisted my ankle. Oh shit, how? And, demoralizing as it may be, I keep going—on the stairs; last week in the shop; literally just before I saw you. On the rare occasions when I don’t lie, I always wish that I had. Wait, what? You’re disabled? The chasm opens again.

I go to the gym every day of the week. No one makes me do it—not because my cerebral palsy is gone, but because I am an adult. My body is a “good” body: It is strong, muscular in places, and tight-ish. It’s not Marcus’s, but I am not Marcus. In the gym, I am recognized, and men I’ve never spoken to nod their head my way.

Nevertheless, I am wary. Do they see that my right side is less muscular than my left? That I sometimes have trouble picking up the weights in a coordinated fashion? That, when I’m fatigued, I drop them just outside the little ridges I’m meant to leave them in? Do they think I’m weak because the weight I lift is low, to make up for my right side’s deficiency? I want to tell them that all of these things are not my fault, but the fault of a rogue forceps blade 23 years ago. I want to show them my medical records, drag them to my gym bench, and point out everything that’s wrong with my form, or my body, or my brain, because then I could stop second-guessing. I could own my condition. But I am not Achilles.

When my dad first overheard me lie about my limp, he was astonished. Within the family, my disability has become an easy, even joked-about, topic. We had a follow-up conversation in which he asked me why I had done that. Exasperated and embarrassed, I pretty much told him to back off. He did, but his eyes said enough: This is not the son I raised. And he was right. I know more than most that difference must be celebrated, and that each time I hide, the shame builds—for me, for others like me. Somehow, I have become the bully, or at least the bully’s accomplice.

I am not sure I want to hide anymore. I’d rather embrace my disability than fear its fallout. But it would be a lie to say I love every part of my body. I am still grappling with the ways I have been made to feel that my body does not belong—and with the conviction that it is easier for everyone that I be a failing normal rather than a normal disabled.

This article appears in the March 2023 print edition with the headline “Struck on One Side.”