Sports Offer More Than Winning

Female athletes have been subject to harmful expectations for years. They want to bring back the joy.

A certain amount of discomfort is required for growth. That’s, in part, where expressions such as no pain, no gain come from—but in sports, that pain is frequently literal. Athletes push their body in order to shave a few seconds off a race time, or gain a point on a routine. In her memoir, Good for a Girl, the accomplished runner Lauren Fleshman shows how this demand for perfection is detrimental to athletes, especially women. The writer Amanda Parrish Morgan is also familiar with the high costs of this culture; in her review, she recalls the glamorization of disordered eating and collapsing on the track. When she and Fleshman were running in the 1990s, women were expected to be not only fast and strong, but also thin, no matter what it took.

Their experiences demonstrate that while sports may seem objective—there’s a winner and a loser, someone is the best, someone worked the hardest—society’s judgments still seep in. The ballerina Misty Copeland has had to push others to recognize her as an athlete: Her art is meant to look effortless, but is still an exhausting physical feat on par with competitive events. Discussions over the acceptability of women’s uniforms have sometimes eclipsed acknowledgment of their skills, like Suzanne Lenglen’s short sleeves and low neck at Wimbledon in 1919 and Serena Williams’s catsuit at the French Open in 2018. Even as women achieve new heights, outdated, dismissive attitudes toward their achievements still echo, like the 19th-century idea that women simply weren’t made for sports—that they couldn’t possibly understand them, let alone master them.

Fleshman makes a case for moving away from a culture of suffering, in part by focusing on the sincere joy of athleticism. Other writers are also trying to do something similar. In her book The Long Run, Catriona Menzies-Pike runs as a way to process the grief from the loss of her parents. She’s not hiding her feelings in the pain, but using every success and disappointment from her training as another step toward “renewal”—as my colleague Sophie Gilbert put it, “running toward something, as opposed to away from it.”

Every Friday in the Books Briefing, we thread together Atlantic stories on books that share similar ideas. Know other book lovers who might like this guide? Forward them this email.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

What We’re Reading

Getty; The Atlantic

When good pain turns into bad pain

“I’ve read before that recovery from eating disorders can be complicated by the impossibility of going cold turkey, as with a substance addiction—we all need to have a relationship of some kind with food, after all. And maybe there’s something of this in the relationship that serious athletes must develop with pain. Where is the line between willingness to be in discomfort and eagerness to be in it?”

Illustration by Paul Spella; image from PA Images / Alamy

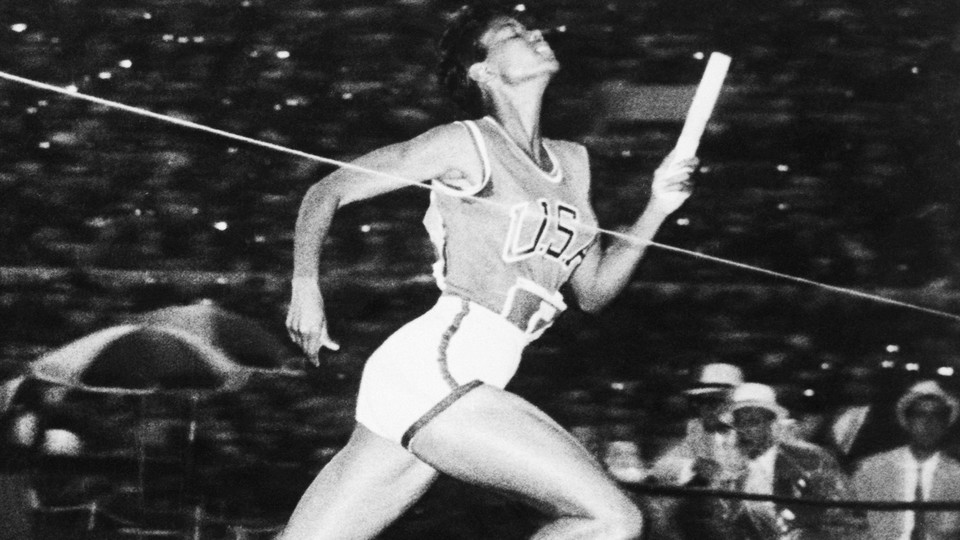

In search of the first female sports superstar

“To the Victorians, the highest aspiration for women’s sports was respectability. Was it ‘unfeminine’ to exert oneself in public? To aspire to beat the competition and seize glory for yourself? To train hard to excel, instead of resigning yourself to life as a supporting actor in someone else’s story?”

Popperfoto / Getty

Wimbledon’s first fashion scandal

“In a sport long associated with country houses and country clubs, the very notion of respectability was bound up with social class as well as gender … Even supposedly ‘respectable’ clothing rarely translated into actual respect.”

📚 She’s Got Legs: A History of Hemlines and Fashion, by Jane Merrill and Keren Ben-Horin

Seiko

“Misty Copeland doesn’t just look like an athlete or act like an athlete; she is an athlete—commercially on top of everything else. Her public image is not just one of a lovely ballerina, be-jeweled and be-tutu-ed, but also of an athlete who is also a savvy businessperson. She has made, just like any famous athlete will, commercial gain from her talents.”

Associated Press

“Less frequently dissected, though, is how often people turn to running as a salve for grief, to impose order on chaos.”

📚 What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, by Haruki Murakami

About us: This week’s newsletter is written by Elise Hannum. The book she’s reading next is Daisy Jones & the Six, by Taylor Jenkins Reid.

Comments, questions, typos? Reply to this email to reach the Books Briefing team.

Did you get this newsletter from a friend? Sign yourself up.