The Art of Survival

In living with cancer, Suleika Jaouad has learned to wrench meaning from our short time on Earth.

Listen to this article

Listen to more stories on curio

This article was featured in the One Story to Read Today newsletter. Sign up for it here.

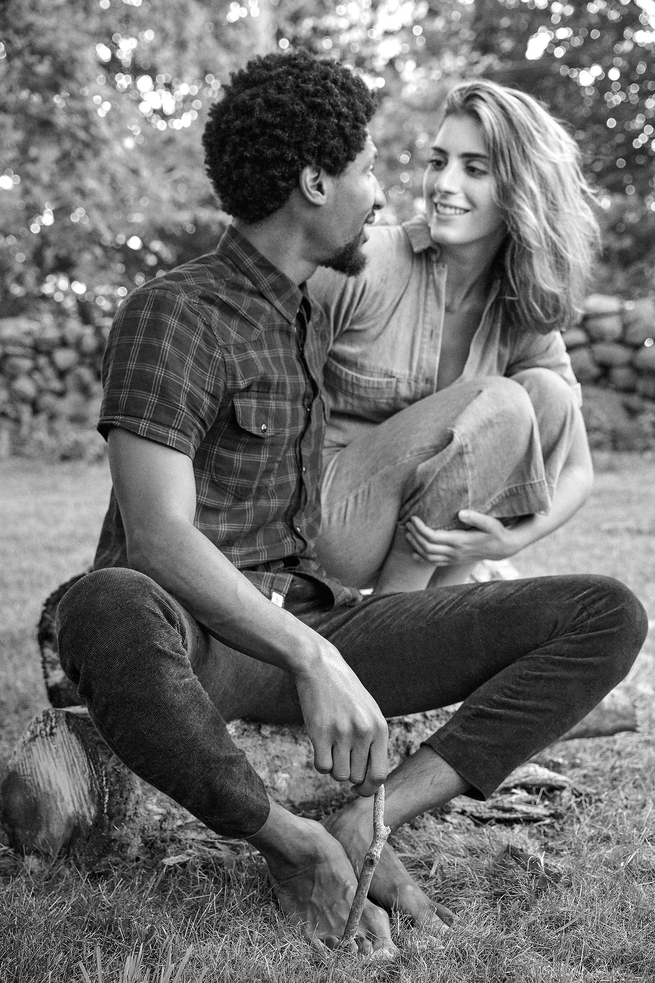

The first time I met Suleika Jaouad, I fell in love with her a little. This, I would soon learn, is a fairly common reaction to Suleika: Everyone who meets her falls in love with her a little. It was 2015, and Suleika was just 26 years old—buoyant, finally off maintenance chemo, and radiant on account of it, her thick brown hair arranged in a boop-a-doop pixie cut. We were attending the same conference, and her boyfriend, a young New Orleans musician named Jon Batiste, was there too. The couple had an irresistible backstory: They first met at band camp as teenagers (she in Birkenstocks, he with a mouthful of train-track orthodonture), and then reconnected romantically as adults. They made for a captivating pair, though the weather systems surrounding them couldn’t have been more different: She was enveloping and collected people; he was shy and abstracted, as if involved in a long, vigorous conversation with himself.

At some point, I was told that Jon was going to be the new bandleader on The Late Show With Stephen Colbert. I remember thinking, Cool, but not much more, having no idea what kind of genius he was. Yet one knew from just looking at them that Jon and Suleika were destined for an unusual life. They were sophisticated and great-looking, ambitious and disciplined, adoring and mutually invested in each other’s success. Suleika had written a column for The New York Times called “Life, Interrupted” about the brutal challenges of living with acute myeloid leukemia, had beaten the disease, and was now doing advocacy work and writing a memoir. Jon would soon be appearing nightly on our television sets and continuing to make music of his own.

They are married now. He’s the more famous of the two, with an Academy Award, a Golden Globe, and five Grammys; he’s also the focus of the documentary American Symphony, which earned him a 2024 Oscar nomination for Best Original Song. (Additionally, Jon is The Atlantic’s first music director.)

But Suleika has her own passionate following. I recently told a friend that I was writing about her, and she started burbling with envy, saying how much she loved The Isolation Journals, Suleika’s Substack newsletter; how much she loved her memoir, Between Two Kingdoms; how certain she was that the two of them would be fast friends if only they could meet in real life. I didn’t have the heart to say: Well, yes, I’m sure that’s true, you guys probably would be friends, but I’m also fairly certain that her hundreds of thousands of readers and quarter-million-plus Instagram followers feel the exact same way.

That’s the thing about Suleika: She’s like O-negative blood, compatible with any type. The awful irony is that almost no one’s lifeblood is compatible with Suleika’s, at least not in the most meaningful sense. Because Suleika had not, in fact, left her cancer behind her. In 2021, she spun out of remission, requiring a second bone-marrow transplant. But her only compatible donor was her brother, Adam, and it was his bone marrow that her cancer cells had managed to outfox in the first place. That means she’ll very likely need a third transplant in the years ahead, ideally from someone else. But there is no one else. Yet.

When Suleika was first diagnosed, in 2011, her doctors put her odds of survival at 35 percent. I asked her in October what her odds are now. “Less than that,” she said slowly, though she added that her prognosis could change if the science does, or if a new suitable donor materializes.

Suleika likes to say that “survival is a creative act,” which has a slightly peculiar ring to it, at once too tidy and too obscure. But what she means, really, is: Living with the implicit or explicit threat of cancer for your entire adulthood forces you to strain the limits of your imagination to find life’s fulfillments. She has surrounded herself with loyal, loving friends. She has made her environments warm and stylish. (Her Brooklyn brownstone was recently featured in Architectural Digest.) But most important, she has made a daily practice of converting pain into art. (She’s fond of quoting the poet Louise Glück: “Writing is a kind of revenge against circumstance.”) Between Two Kingdoms spent 22 weeks as a New York Times best seller. This summer, she will have her first art exhibition, inspired by the watercolors she did in the hospital during her second transplant. She has a contract for two more books, one a compendium of writing prompts and meditations on journaling, the other a collection of her paintings and essays.

The self-help aisles are heaving with advice about how to be happy. But it’s one thing to read such guidance; it’s another to actually live it. Yet at 35, Suleika is sharing with her readers how she’s trying to do the hardest thing, even if it’s the most basic thing: wrench meaning from our short time here.

A brief confession before we go any further. I had a meta-motive for wanting to sit down with Suleika: When our interviews began, I was on month 16 of long COVID. There’d be days when I was too dizzy to sit, let alone stand, and my head would judder and vibrate like a lawn mower if I started to walk. Suleika was the one person I knew I could interview while lying down.

I was all too aware that there was an existential gap in our suffering, but I still wondered if, from observing her, I’d learn something about how to cope, just as thousands of other physically and spiritually broken people had. She’d figured out how to stop resisting her illness, spending many productive hours from bed, hadn’t she? Whereas I was still in an iron mode of resistance, braying at the gods.

It’s easy to miss Jon and Suleika’s home in the Delaware River Valley. It is also easy, once you find it, to mistakenly believe that it is inhabited by hobbits. They live in a compact, cheery farmhouse, the walkway lined with solar-powered lanterns, the grounds checkered with wild shrubs and pyramids of gourds. This is where the couple retreated during the pandemic, and it is where I went the first night I had dinner with Jon and Suleika, along with four of their friends. The atmosphere at the table was relaxed and festive, and everyone was almost unnaturally attractive, like castoffs from a rom-com that never went into production. After dinner, Jon took a seat at the piano in the living room, and one of his friends, the saxophonist and mathematician Marcus Miller, joined him. Their improvising was exactly as great as you’d imagine. Crazier still? Everyone acted like it was no big deal. To me, it was a penthouse scene in a Noël Coward play; to them, it was a Monday.

The next morning, I opened my phone to reexperience my favorite moment of the evening. We are all still eating dinner. Jon has called up a song on his phone from the gospel artist JJ Hairston’s Not Holding Back, one of two featuring Pastor David Wilford. Jon is not just luxuriating in it; he’s doing that thing, that Aeolian-harp thing, where he lets the music ripple through him, practically becoming it. He’s involved in some dialogue with Marcus about it too, one that’s primarily gestural, marveling at all the choices Hairston and Wilford made, chuckling at them, nodding, pointing, and exuberantly mugging: Jon fans himself as if he’s an overheated lady at church; he mock-plays along on an imaginary piano; he stomps his foot; he jumps and hops; he opens his eyes wide and punctuates every few bars with “Ohhhhh!”

“We gotta start it back from the beginning!” Jon cries, holding his hand up. And he replays the song.

“OHHHH!” Jon whoops.

You’re gonna live …

You’re gonna live …

You’re gonna live …

You’re gonna live …

You’re gonna live …

to see it happen.

(Jon fans himself.)

You’re gonna live … to seeeeeeeeee it happen.

I said live live live live live!

(Jubilant piano riff here, which Jon pantomimes with a flourish.)

Live live live live live!

Jon is now singing to everyone at the table, pointing at us, serenading us with: “You’re gonna live … to seeeeeeeeee it happen.”

“I don’t know what you’re going through,” Pastor Wilford sings.

“But whatever it is—” Marcus’s fiancée says, spontaneously.

“—I’m gonna live,” Suleika replies.

Only then did I notice the lyrics.

I’d heard them at the time, but they hadn’t really registered.

She’s going to live: a prediction, a command, a dearly held wish.

A chilly Monday morning in Brooklyn this past October. I meet Suleika at her brownstone at 7 a.m. Her left eyelid has been drooping for months, and her doctors want an MRI of her brain to rule out anything ominous. As we head off to the brand-new Brooklyn arm of Memorial Sloan Kettering, she pulls on a giant overcoat with a Basquiat design. “My hospital jacket,” she explains. She especially loved wearing it after her hair and eyebrows had fallen out. “Instead of looking at me, people would look at my coat.”

Our Uber pulls up in front of Sloan Kettering, and I sit in the waiting room. After about 45 minutes, Suleika emerges. I ask how it went. The usual clanging and banging, she says. “The story I told myself this morning is that I was in an avant-garde nightclub, and the band playing was called the Woodpecker Collective.”

Suleika’s cancer started, as she wrote in Between Two Kingdoms, with an itch. It was a tenacious itch, one that originated on the tops of her feet and gradually coiled up her legs. Then came the naps. Naps begetting naps begetting more naps. But this was 2010, Suleika’s senior year at Princeton, and everyone was tired their senior year, right? She powered her way through with energy drinks, Adderall, and the occasional line of coke.

That fall, Suleika got a tiny furnished apartment in Paris, went to work as a paralegal, and was soon joined by her then-boyfriend. For a few months, life was grand. But she was still tired, so tired, and she kept getting infections that drove her to the local health clinic. On the day she finally dragged herself to the American Hospital of Paris, she fainted on the sidewalk. The doctors tested her for everything “from HIV to lupus to cat scratch fever,” she wrote. But never leukemia.

Suleika stayed in the American Hospital of Paris for a week, buoyed by fresh croissants and steroids. But shortly after being discharged, she was back, her mouth covered in sores, her complexion “blue-gray, like dead meat.” The doctor told her that if her red-blood-cell count got any lower, she wouldn’t be allowed to board an airplane. She flew home. Two weeks later, she received her diagnosis.

In 2021, when she feared she had relapsed, Suleika’s medical team didn’t recommend doing a bone-marrow biopsy, even though her blood counts had been dropping for two straight years and she’d been feeling depleted. There were plausible explanations, of course: She’d had Lyme disease and a host of infections; she was, as always, working without cease. But ultimately, Suleika had to demand a biopsy, and she likely wouldn’t have gone through with it if her friend, the writer Elizabeth Gilbert, hadn’t cleared her schedule to accompany her.

“I get there, and they’re like, ‘We don’t have to do this. We’re just doing this to ease your anxiety,’ ” Suleika tells me. “And I felt so embarrassed, like I was being melodramatic.” Women: so high-strung, so fluttery.

Suleika could go on about the tar pit of biases that lurks beneath her medical encounters. At 22, for instance, she wasn’t told by a single doctor that her treatments would likely leave her infertile; she found out on the internet (and quickly harvested her eggs). Nor did she know that her leukemia protocols would shunt her into menopause; her fellow female patients had to tell her. And certainly no one told her that she had multiple options for mitigating her pain; she had to learn about that from her younger friends in the pediatrics ward.

“Why can’t we apply the same principles that we do in pediatrics to adult care?” she asks me. “Small things, like putting on numbing gel for accessing ports.” Or big things, like biopsies. They’re positively medieval procedures, with a long, wide needle boring deep into the core of your pelvis. Kids get them under sedation. Adults typically receive only a local anesthetic. During her 2021 biopsy, it took the doctor four tries to get what she needed. Suleika bit down so hard on her hand that it bled.

“It was the grisliest thing I’ve ever seen,” Gilbert told me. “It was like a paper punch going through bone.”

Now, for her biopsies, Suleika asks to be knocked out.

It is tempting to look at Suleika’s illness as an origin story, the thing that forced her to live an exceptional life. But another way to think about it is that Suleika is an exceptional person to whom illness happened. Speak with her friends, and you get the sense that she has always lived her life like the rest of us, but in a much larger font.

When Suleika falls in love, she falls ferociously in love; with female friends, she’s the queen of the grown-up sleepover and intimate discussion. Her intensity revealed itself early. In fourth grade, she started the double bass, and by the time she was 14, she was practicing five hours a day. In 11th grade, she was rising at 4 a.m. each Saturday to commute to Juilliard from her home in upstate New York. At Princeton, she also played in the orchestra, but almost no one knew about it, because her life already looked so full. Lizzie Presser, her closest friend, remembers being at a costume party when Suleika abruptly turned to her and said, “Shit, I’m late.”

Late?

She had to be onstage with the Princeton University Orchestra in a matter of minutes.

“She never talked about playing,” Presser told me. But they left the party, and Presser went to the balcony of the main campus auditorium. “The curtain comes up, and there’s Suleika in the center, in a white flapper dress that barely covered her thighs, and she’s in the role of principal bass—flanked by men in tuxes! Surrounded by them like a flock of birds.”

After Suleika was finally diagnosed with cancer, roughly a year after graduation, she got very, very sick, and to make her better, her doctors had to make her sicker, poisoning her with what they hoped would be enough chemotherapy to drive her leukemic blasts below 5 percent, a requirement for receiving a bone-marrow transplant. The process took nearly a year.

For a few months, she stared bleakly at the television, watching episodes of Grey’s Anatomy. She tried reading cancer memoirs, but most of them disgusted her, with their tyrannical emphasis on grit and story arcs ending in triumph. “At that point, I was going into bone-marrow failure,” she says. “I frankly didn’t think I was going to make it to transplant. So reading those stories sort of felt like a middle finger.”

Yet she always kept a journal. Eventually, that journal became a blog, and one of her blog entries became a story in HuffPost and earned her a call from an editor at The New York Times. Sensing that her time was now limited, Suleika found herself asking, at 23, if she could have her own weekly column about what it was like to be a young person with cancer—oh, and could it have an accompanying video component too?

The series would win her an Emmy.

Suleika’s column became a phenomenon, speaking to a far greater range of people than she ever imagined. She heard from a senator’s wife who was struggling with fertility issues, a high-school teacher in California who’d lost a son, a prisoner in Texas who was trapped on death row. Everyone seemed to have a shame-and-pain part of themselves, or an unreconciled sadness, a private perdition.

In April 2012, she underwent a bone-marrow transplant, and a few months later, her doctors told her it seemed to be working, but cautioned that it would be many months more before they knew for certain. She spent the next two years mainlining a toxic slurry of maintenance chemo, which left her feeling wretched, exhausted, seasick. When the treatments were finished, she realized that she no longer had any idea how to live among the well. So she cooked up an ambitious project for herself, deciding that she and her dog would make a 15,000-mile, 33-state loop around America, with the aim of visiting many of the correspondents who’d moved or inspired her.

It should be noted at this point that Suleika did not yet have a driver’s license.

That trip became the second half of her memoir, which became one of the best modern chronicles of cancer and its aftermath, a broad-spectrum rendering of illness’s many physical and psychological hues. (Especially the fury. God, how I loved the parts about the fury.) In a review on Instagram, the author Ann Patchett went so far as to say that she might not have had to write Truth & Beauty, her stunning book about her friend Lucy Grealy, had Suleika’s book already existed.

In the years since, Suleika has continued to write, both essays and reportage. (An article she did for The New York Times Magazine about prison hospice was especially good.) She made dogged but unsuccessful efforts to get her Texas prison correspondent off death row. And she has built a variety of communities, both virtual and embodied.

She originally purchased her home in the Delaware River Valley, for example, to be among an enclave of artists and writers who had already settled there, but she has also since befriended the locals, including her neighbor Jody, a building-trades guy with four missing fingers (childhood accident) and a business card that says I’m 60. I know shit. Call me. In Brooklyn, Suleika lives within a couple blocks of Lizzie Presser, but she also socializes with Presser’s mother, sometimes independently, and she’s become so close to the couple next door that she now plans to build a walkway between her back terrace and theirs.

And Suleika has magicked an entire community into existence with The Isolation Journals, a virtual salon designed to help readers access their own creativity when the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune have punctured their lives. Hatched during the third week of the pandemic (Suleika reckoned she knew a thing or two about the unnatural rationing of human contact), the newsletter offers writing prompts, video discussions with artists about the creative process, and reflections on how to focus on the good while acknowledging the terrible.

Suleika discovered that she’d tapped into a deep human need. Her Substack now has more than 160,000 subscribers. When she informed them in December 2021 that her cancer had returned, she received hundreds of care packages and old-fashioned letters in the first week alone.

During her relapse, Suleika startled everyone with yet another reinvention, declaring, after completing her first watercolor, that she was going to be a painter. “It seemed,” her friend Carmen Radley told me, “like it came out of nowhere.”

But it both did and didn’t. Suleika tends to live in generative mode; that’s her reflex. Part of the reason she took up painting was because she was on such a potent drip of psychoactive medication to subdue her pain that it blurred her vision too much to write. (A combination of ketamine and fentanyl. At one point, she hallucinated a menacing French child named George.) Her paintings from Sloan Kettering have a visceral, fantastical quality, usually featuring some colorful mix of animals and her ravaged body threaded with tubes. She likes how wild and imprecise watercolor is, how improvisational, so different from the careful calibration of writing. It’s an adventure in “happy accidents.”

In the late fall, during an event at Princeton, she was asked by an audience member what advice she’d give to someone who was hesitant to mine their emotional reserves to create something.

“Give yourself permission to be a bad artist,” she said.

I’m back at Suleika’s house in the Delaware River Valley. She greets me at the door and shows me into the kitchen, where on the counter I see a rainbow box of pills. Inside is a monster’s miscellany of antivirals and antiemetics, antibiotics and immunosuppressants—and she’s not even doing chemotherapy, in defiance of her doctors’ wishes. This is the minimum that a transplant patient like Suleika requires.

Suleika and I start chatting on her couch in the living room. At some point, Jon, who’s been fussing in his music studio, pads into the room carrying three books, one so corpulent, it looks like it might bust its own spine. It’s David J. Garrow’s 1,472-page volume about Barack Obama.

“What do you think?” he asks me.

I tell him I haven’t read it and therefore cannot offer an opinion.

He gives a sly smile. “Oh yes, you can.”

What to make of Jon? At first, he terrifies me. He plays 12 instruments, the bulk of which he taught himself. He’s a man of unflagging Christian faith, pure and indivisible: You sense that he’s living for a higher and more serious purpose, faithfully reading scripture, never indulging in caffeine or drugs or alcohol. But most striking is his magpie creativity, his hungry and wayfaring brain. For a while, I worried I was boring him.

Beyond that, Jon is often hard to read, and he’s a person who tests a writer’s descriptive powers. What you really long for when you’re near him is the accompaniment of sound effects, audiotape, videotape; without them, it’s almost impossible to give the full measure of the man. He talks to you slightly sideways, his body angled away from you at 45 degrees. When he’s energized, he doesn’t jump so much as boing. He’s a mesmerizing combination of gnomic insights and probing questions, of silences and sudden joyous yowls (“Yeaaaaaaaahhhhhh,” “Woooooooo,” etc.).

Suleika mentions that Jon spent forever lugging around a box set of Stephen Sondheim lyrics. I ask if he knew Sondheim. Turns out that he not only knew him, but also corresponded with him until he died—and did a special arrangement of two pieces from Assassins for him for his birthday.

“Is there a recording of it somewhere?” I ask.

“Yeah.”

“Where?”

“On my phone!” Sure. Because we all keep private birthday gifts to Stephen Sondheim on our phone. “You want to hear it?”

Not long after that, I become relaxed around Jon. The turning point arrives when Suleika briefly steps outside with their dogs. I confess that in the face of other people’s suffering, I sometimes become a stammering stumblebum. How does he always seem to know the right thing to say to Suleika?

“It’s like music, to say the right thing,” he says. Then a long pause, even by Jon standards. “It requires”—another pause—“being attuned to the moment. And the person. And yourself all at once.” A third pause. “It’s really less about the right or wrong thing to say—or to play. Because people feel what you’re saying more than hear what you’re saying.”

His phone rings. He goes outside to take the call.

In that moment, it dawned on me: Jon and Suleika are both emotional seismographs, keenly aware of other people’s sensitivities and vulnerabilities. They’re just outfitted with different drums.

“That’s a common misconception about Jon—that he’s in his own world, that he’s lost in the music in his mind,” Suleika says. “But Jon sees, notices, everything. Everything. He can sense when I’m anxious even when I don’t realize I’m anxious.”

And honestly, I should have known this before, based on Matthew Heineman’s American Symphony. It’s a beautiful film, following a co-occurring high and low in the couple’s life in 2022, with Jon reaching the pinnacle of his career—nominated for 11 Grammy awards, hard at work on an original piece of music to be performed at Carnegie Hall—at just the same moment that Suleika is vividly relapsing. You see Jon tenderly shaving Suleika’s head; you see the two of them playing a version of Simon Says, with him mirroring her every movement as she makes her way down a hospital hallway, yoked to an IV pole.

He takes the “in sickness and in health” part of his job extremely seriously. Jon proposed 24 hours after Suleika discovered that she’d relapsed.

But when Suleika is well, she’s the one who makes Jon’s life possible. Until he began dating Suleika, Jon lived like a nomad, touring with his band around Europe and the U.S., usually in a rented van, and staying in run-down hotels. His apartment was a dragon’s nest of, in Jon’s words, “papers, music, manuscripts, gifts, awards, clothes, pawn-shop instruments, laptops.” The first time Suleika spent the night, a spider bit her on the eye.

Whereas Suleika has an abiding urge to nest, having lived on three continents with her Swiss mother and Tunisian father by the time she was 12 years old. (And she always lived modestly—her mother came from a tiny village and her father’s parents could not read or write.) Her focus on home and friendship has provided Jon a bulwark against the devouring demands of fame. If it weren’t for Suleika, it’s also possible that he’d work until he expired. He has the nocturnal rhythms of a bat.

Jon wanders back inside again. The call has clearly keyed him up. He beelines for the couch and climbs on top of Suleika, planting himself face down in her lap. “Mmmmmmmm,” he moans. “I’m an overstimulated introvert.”

“I think one of my roles in Jon’s life is to soothe his nervous system.”

If you hadn’t met Suleika, I ask, what would your life look like?

“I don’t know,” he says. He thinks. “I’d be going too fast for the machine.”

So she’s a brake pedal?

“More elegant than that. A brake pedal ? No.”

Sorry, I say. I can’t do machine metaphors.

“She’s the software that calibrates the machine,” he explains, his face still buried in her lap.

Whenever Suleika is at her lowest, she always manages, somehow, to make her most creative leaps. During her last transplant, even when she was at her most despairing, even when she was as close to death as she thinks she’s ever come—her throat too scorched to speak, her body simmering with three different infections—she summoned the strength to prop herself up and paint at 2 a.m., when she was seized by an image of a marionette being borne away by birds. She kept paper and watercolors right next to her bed.

But me? Even with a far more benign illness, I do no such thing. I have not taken up knitting, or making collages, or writing fiction or doing macramé or conjuring an online haven for long-haulers. Instead, I’m just sad and stuck. How, I ask her one day, has she managed to make such a productive life for herself, in spite of all the shit? It requires so much energy.

“It takes a lot more energy to do battle with demons,” she points out. Meaning one’s own depression.

Yes, I say, but that’s a rational answer. Demons aren’t rational. Some of us feel like we’re made of those demons. I would currently say I am 86 percent demons.

“I think I had to get to a place where my sense of despair—and boredom, honestly—was so great, I had to do something,” she says. “That sent me on this research project about all the different bedridden artists and writers and musicians throughout history who’d figured out creative work-arounds.” Like Frida Kahlo. “Her mom gifted her a sort of lap easel and attached a mirror to the canopy of her bed.” Or Henri Matisse, she adds, who, when he was old and infirm, affixed a bit of charcoal to the end of a long stick and drew studies for the Chapel of the Rosary on the walls of his apartment, all while lying in bed.

But Suleika recognizes she’s had many years of practice when it comes to living horizontally. “I can also understand,” she tells me, “as I’m saying all this, if your response is a bit like, Fuck you. Nothing about this feels good or will ever feel good or can ever be useful. I’ve been in that place too.”

Like binge-watching Grey’s Anatomy, for instance. Which is about where I’m at, I tell her.

“I sometimes worry that I’ve become the kind of person who makes people who are not ‘suffering well’ feel like shit,” she confesses.

Suleika makes her living in the first person, actively writing about her life and pressing “Send” each week. But at some point, I begin to wonder whether there’s another Suleika, a more private Suleika, tucked inside the public one. Her readers now expect her to be a certain kind of inspirational person. Does she even have the freedom to maneuver through the world without being that woman?

It took time for me to realize that Suleika is sometimes selective about what she shares.

Here is one part that we do not always see, for instance: how much she suffers. Those high-gigawatt drugs she takes can have brutal side effects, and she’s routinely subjected to torturous procedures.

“Suleika is who she is on the page,” Elizabeth Gilbert said. “But that identity is flanked by two characteristics that I’m not sure anyone understands the extent of.” One is that she’s got a punk, rebellious streak. But the other “is how fucking tough she is,” Gilbert said. “How fucking stoic. She’s a Marine.” After that excruciating biopsy, she and Suleika went out to dinner. “If that had been me, you wouldn’t have seen me for a week.”

Some discomfort is so routine for Suleika that she never bothers to discuss it. In January, shortly after she appeared on the Today show with Jon to promote American Symphony, I told her she did great.

“I projectile-vomited in broad daylight in the streets of New York City afterwards,” she replies, with startling matter-of-factness. “Right before my next thing on Park Avenue.”

She … what? I try to imagine Suleika, made up for television and in a blazer of elegant blue velvet, vomiting on the Upper East Side.

“I have vomited in public more times than I can count,” she says. “I’m always trying to find a private spot between two parked cars or behind a tree. Often I don’t get there.”

So: Chronic nausea barely rates a mention in her work. Also underdiscussed: Suleika is always and forever tired. But how many times can you write that you are always and forever tired? Yet she is, with only a few good hours a day, usually. Nor does Suleika dwell on the fact that she’s a regular stewpot of respiratory infections. She’s been sick all winter with one thing or another.

“Every dinner since you’ve been to my house,” she says, “I’ve left either halfway through or shortly after while everyone’s hanging out and having fun. I go straight to bed and I don’t say a word. I call it my ‘Tunisian exit.’ ”

Her relentless fatigue and nausea and infections have an ancillary consequence: anxiety about making plans. “Like, will I be well enough?” she explains. “Should I just cancel now so that I don’t mess up anybody else’s schedule? Or will I feel well that day and regret that I canceled? I have that conversation with myself about every single preplanned social activity or work commitment.”

On December 24, Suleika’s Isolation Journals newsletter talked about her first experience hosting Christmas, for which her mother, father, and brother flew in from Tunis. She described the “obnoxiously” large tree she purchased, the two-hour meeting her family had about their dinner feast, the old-school paper snowflakes her mom pasted to the windows.

What she didn’t write about was how she felt, which was terrible, or how many holiday plans with her family came undone. “Since pretty much mid-December, I’ve barely been able to function,” she tells me. “I spent all of Christmas in bed. We were going to go ice-skating. We were going to go Christmas shopping in the city. We were going to do all the things, and I didn’t do a single one.”

Suleika often writes about trying “to hold the beauty and cruelty of life in the same palm.” But one wonders if writing so publicly and so frequently—if being an inspiration to so many—makes her feel some unconscious obligation to focus more on the former. When Between Two Kingdoms came out in February 2021, Suleika already suspected something was amiss. Her blood counts were dropping, she was always tired, and she had blistering migraines. But she was so elated that her memoir was finally out there in the world that the joy energized her. On her publicity tour, she told interviewers that yes, she was cured.

“I would hear all the time from people with similar illnesses,” Suleika says. “People who’d write to me and say, ‘You give me hope that this can be my life too, 10 years out.’ ” When her doctors finally confirmed she’d relapsed, in the fall of 2021, it spooked her so much that she didn’t share the news in The Isolation Journals for three weeks. “I felt awful,” she says. “The very particular weirdness of having a public platform related not just to illness but to survival …” She trails off.

“Because Suleika has the exuberance that she has, the force of will that she has, I sometimes forget that she has gone through what she’s gone through,” her friend Carmen Radley said. “Superhuman people aren’t afraid of getting sick again, are they? But I think she was terrified of it.”

That’s really the thing her readers don’t always see: the fear.

And it’s not because Suleika is dishonest. It’s because she is, as Gilbert says, so fucking stoic. It’s because her quotidian nausea is relative to the pain of, let’s say, vomiting up the entire lining of her esophagus, which she has done more than once. It’s because she doesn’t want to cause a fuss over every upset when there may come a day when she needs the cavalry to come charging in at full gallop. It’s because she doesn’t want her relationship with Jon to be defined as that of a patient and caregiver. “I don’t want people to view me first and foremost as a sick person,” she says.

But fear is what she is now experiencing, during our phone conversation in January: the prospect of a second relapse and a third transplant. Why is she getting so many respiratory infections? Why is she always so tired? Why, when she went back on Adderall recently (common for post-transplant patients, to boost their energy), did it do absolutely nothing? “I’m like, Did I get some dud pills? ”

She has not written about this anxiety. “To say it out loud,” she says, “is to make it real.”

She is bracing herself for another biopsy next week. If the cancer has returned, her brother remains her only donor option. The bone-marrow registry tilts very heavily toward white people, because the bulk of the donors are white—a problem so personally relevant and galling to Suleika that she’s become involved with an organization called NMDP, formerly called Be the Match, to encourage more people to donate.

Ever since her second transplant, in 2022, Suleika has had night terrors. Once, while fast asleep, she hit Jon with a closed fist. “And then I did it again the next night,” she says. “I was so scared of doing it again, I wanted to sleep in the guest room, and Jon said, ‘No, we have to sleep in the same bed.’ ” For six weeks, she saw a sleep therapist.

Suleika both writes and talks, with surprising clarity, about the philosophical problem of living with uncertainty. But there’s a reason that liminal places are often depicted as more hellish than hell. The betwixt and between is where the tortured ghost of Hamlet’s father rattles around, boiling with rage and sorrow. It’s where Hamlet himself dwells—trapped between childhood and adulthood, uncertain whether he wants to live or die.

It’s the time between biopsy and results. Which in some larger sense is every day if you’re Suleika—not knowing, with the recurring specter of acute myeloid leukemia, if you have months left on this planet or 50 years.

“I do feel like I’m living my own double life sometimes,” Suleika says, “in terms of how I’m feeling and what I’m sharing and showing—not just to the world, but even to the people closest to me. And to myself.”

Jon is playing a concert at Carnegie Hall in the run-up to his 2022 appearance at the Grammys. He’s seated at the piano.

“I want to dedicate this last one to Suleika,” he tells the audience.

Then there’s silence. And more silence. And more and more silence. Jon is staring intently at the keys. This is perhaps the most spellbinding moment in American Symphony. The camera becomes so uncomfortable with Jon’s stillness that it pans slowly down to Jon’s fingers, still lingering on those keys, and then slowly back up to his face.

The live audience, even the viewing audience, doesn’t know it, but Suleika’s hospital bracelet is in his pocket.

He finally begins to play. Tunefully and deliberately at first, but soon frenetically and repetitively, and then dissonantly and angrily, a blur of hydraulics, until out of this chaos emerges something utterly freaking majestic.

I later ask Jon what was running through his head in that long moment of quiet.

“Mmmmmmm,” he says. “Don’t force life.”

“I understood you to be in prayer,” Suleika says.

“That’s what it is,” he says, looking appreciatively at her. “Psalm 46: ‘Be still and know I am God.’ The most natural state is in a state of prayer. Stillness. Knowing. Connected to the love. And then you can send it to the person.”

He turns back to me. “That whole concert—the concept was to sit at the piano for two hours straight with no music and no preparation,” he says. “It was called ‘Streams,’ like stream of consciousness. The divine stream, where all things creative come from. You can always dip into it if you have access to that.”

Suleika’s. Latest. Biopsy. Is. Negative! When we speak on the phone again in late January, I can hear her relief.

But I still hear anxiety, even fear. As if she’d received dreadful news. In fact, she had.

Just before her biopsy, two of her young friends with acute myeloid leukemia had relapsed. One is in her mid-30s and has two young children. The other had been doing great, jetting off to weddings and resuming her day job. Then, one week after receiving perfect labs, she went into cardiac arrest. Her doctors told her she was likely out of options.

The day before her biopsy, Suleika and her father went to visit this friend in the hospital. “It was just heartbreaking,” she says, “and, selfishly, terrifying.” The experience was like staring at a green-gray hologram of the potential future. When she saw her own nurse, she asked for one, just one, reassuring anecdote. “And she was like, ‘Well, we have one guy who just had a second bone-marrow transplant, and he’s doing great.’ And I was like, ‘That’s not helpful to me. I want stories of people who are 20 years out and thriving.’ ”

Suleika’s case is practically without analogy. Her team likes to call her “a medical unicorn”: Almost no one relapses as far into remission as Suleika did.

“When you have a recurrence, the tenor shifts,” Suleika says. “People are no longer saying, ‘You’re going to beat this; everything’s going to be okay.’ ”

Seeing her friend reminded Suleika, for the umpteenth time, that the membrane between health and illness is thin. And Suleika had just enough reason to remain nervous about her present state. Her “chimerism”—the percentage of her brother’s donor cells versus her own—had recently slipped down to 99 percent. The doctors had assured her that small fluctuations were normal. But she wasn’t going to exhale, clearly, until she learned she wasn’t continuing her descent. “I’ve gone from being in a mode of recovering from this most recent transplant and trying to get my life together,” she says, “to shifting into a place of being afraid of relapse.”

I wonder whether forgoing maintenance chemo this time around has also compounded her anxiety. After her second transplant, Suleika’s doctors urged her to continue it in perpetuity. She lasted less than a year. There was no life in her life, just intolerable nausea and listlessness. On one of the rare evenings that she rallied to leave her home—a state dinner at the White House in December 2022; Jon was performing—she felt queasy throughout, terrified that at any moment she’d throw up in front of the Bidens. She decided to stop chemo.

But Suleika says she has no regrets about having stopped, given that she was never especially convinced that chemo would even extend her life. Rather, what frightens her is that remission is a fragile state—something she learned firsthand in 2021. “I have a ticking clock in the back of my head,” she says. “Now I’m thinking I’ll be lucky if I get to five years before relapse.”

So here we are, back where we started: How does one live with an everyday, every-hour awareness of how much healthy time might remain—perhaps all the time that might remain—as a very specific math equation? How does this translate into creative habits, a modus vivendi, a philosophy of life?

“For me,” Suleika says, “it means building a world in my home right now. It means gathering the people I love most and spending as much time as I can with them. It means bringing home foster dogs every month, practically, even though nothing about that makes sense for our lives right now.” During her spells of insomnia, when the cancer goblins are rapping at her consciousness, Suleika scours Petfinder.com for underloved runts. “It means drilling into projects I’m most excited about,” she continues, “but it also means creating unstructured time for reading and exploring and painting.”

She’s doing, as she likes to say, “all the things.” Or as Anthony Burgess wrote in Little Wilson and Big God: “Wedged as we are between two eternities of idleness, there is no excuse for being idle now.”

A few months earlier, while we were lying on the couch in her Brooklyn brownstone, I had screwed up the courage to ask Suleika how often she thinks about her own mortality.

“I think about it,” she told me. “I’m not afraid of death. I’ve now witnessed enough people die and been with them in those moments.”

How about Jon?

“Jon is deeply afraid of death.”

His or yours?

“Everyone’s. But very afraid of his own death.”

Has he talked with you about how he’d do—or what he’d do—if you weren’t there?

“He won’t talk about that with me.”

Do you want him to?

“No. Because I don’t think he can. It’s too painful for him.”

He is carrying a lot. And he’s more vulnerable, more sensitive, than his iridescent shell would suggest.

“I know Jon is not my child,” she said. “But I also worry about—I was going to say orphaning him, but that’s a little too Freudian.”

Actually, I said, I think it’s pretty common for spouses to fear abandoning each other.

“I think I feel that way in particular about Jon because …” She spoke carefully, thoughtfully. “I know him so deeply and I know how unknown he is to most.”

Yet it is also Jon, powered by his faith and his bottomless drive, who helps keep Suleika moving toward that future he’s determined to have.

“Daydreaming can feel really dangerous when you don’t know if you’re going to exist in the future,” she told me. “It becomes an act of willful defiance. So I force myself to have a five-year plan.”

And part of that plan, she now informs me, isn’t just completing two books, but a very different sort of birth.

She and Jon would like to take concrete steps toward having a child in the near future.

In spite of the uncertainty.

In spite of what Suleika calls her “survival math.”

“Jon is really helpful to me here,” she says. “It’s the same logic he applied to getting married the night before the bone-marrow transplant, which is: We had a plan, and we are not going to let this get in the way of our plan. This is how Jon operates in his life in general. He dreams as big as he can dream and lets nothing hold him back until he’s done absolutely everything in his power.”

Suleika has written about how she doesn’t want to have a baby only to abandon the child. She still has those concerns.

“But I’ve talked about it with the Miles family.” She’s referring to dear friends with three kids of their own. “I’ve talked about it with Lizzie G. and Lizzie P.” Meaning Gilbert, Presser. “And they were like, If that were to happen, your kid will be surrounded by so much love.” From Jon above all, but also from them, from many others. “What Jon has ultimately said to me,” she says, “is that the most important thing is for a child to know how deeply loved they are. And whatever future child we have—whether it’s biologically our own or adopted or we become foster parents or just really doting aunties and uncles to the other people’s kids—there are many ways to do this.”

Two days after we speak, I get a text from Suleika: “Some good news just rolled in!!! Back to 100, baby.” Her chimerism is no longer at 99 percent. With this news, her mood improves; the familiar buoyancy returns.

Yet even before she knew this, Suleika was forging ahead, refusing to let her past define her future. How many of us can do that? The past is the ragged territory from which we take our cues, make our most basic assumptions. But planning for a child: That is a rejection of a life interrupted. That’s an insistence on continuity.

Continuity is the implicit subject in one of her most striking paintings. It’s a colorful oceanscape of jellyfish, a life form that fascinates Suleika, particularly the Turritopsis dohrnii, considered in some sense to be immortal. Whenever it’s injured, it reverts back into a polyp, eventually releasing tiny jellyfish genetically identical to its previous adult self. It’s a creature that reincarnates, continues on, in response to—and in spite of—mortal threat.

Children and art: the two most meaningful things, Stephen Sondheim famously wrote, we mortals can leave behind. Suleika’s life’s emphasis, always, has been on the act of creation—and communicating to others how essential it is to who we are. Children and art, children or art, the courage to create: Those will be her legacy, no matter what.

This article appears in the June 2024 print edition with the headline “The Art of Survival.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.