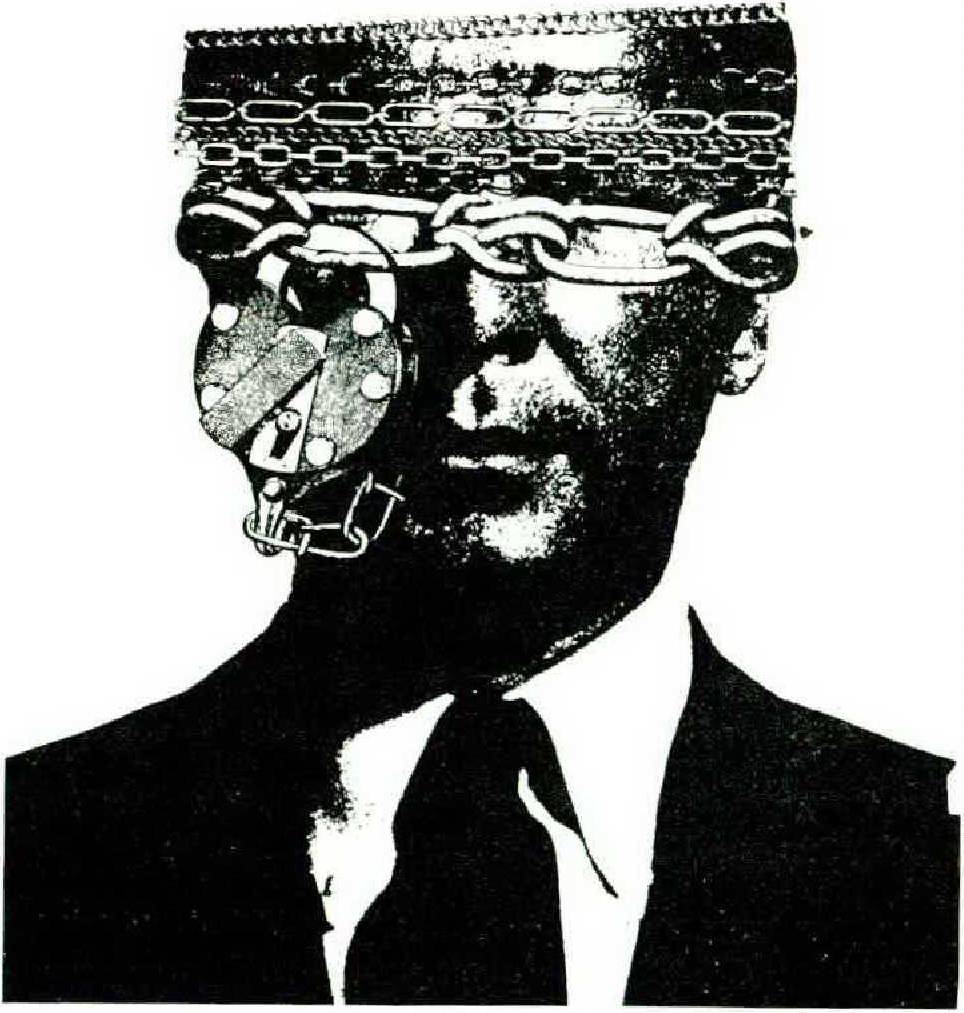

The Language of Politics: Arise, Ye Prisoners of Jargon!

“Our words do much of our thinking for us; we are necessarily manipulated by them.”

Confucius once said—yes, he said—that the “rectification of names” is perhaps the main business of government: “If names are not correct, language will not be in accordance with the truth of things.”

What a prescription! None of us, as far as I know, looks to politicians for the “rectification of names.” We do not expect them to make clear what they mean by the words with which they spatter their speeches. To try to analyze one of their speeches is like trying to separate the flakes of rolled oats in a bowl of porridge. If they have no economic policy, they nevertheless give a name to what they do not have: “stop-go” it was called in Britain in the 1960s; “Phase I (and II and III and IV)” in America in the 1970s. Extraordinarily, we do not challenge this language; we accept it, and use it ourselves. Most of the time, to put it bluntly, we simply do not know what we are talking about.

Perhaps a personal example may be allowed at the beginning. The first volume (A-G) of the new Supplement to the Oxford English Dictionary identifies me as providing the locus classicus for the term “the Establishment” when I first used it in its contemporary meaning in 1955. I have to confess that I feel as if I have been knighted, and a friend has suggested that I should henceforth insist that envelopes be addressed to me as “Henry Fairlie, l.c.” Certainly, when I first gazed at the entry, I wondered if there was any place left to go but down.

In The New Yorker, a few years ago, I described the rather haphazard way in which I first came to use the term “the Establishment,” and tried to explain why it has made such an antic journey into the languages of I do not know how many countries. (A German scholar has told me that the correct translation of the word into German would contain at least seven syllables.) Not a day now passes when the phrase is not shouted, or whispered, back to me; and I have long since ceased to inquire what people mean by it. It seems to me now to have little or no meaning, and I rarely use it any longer.

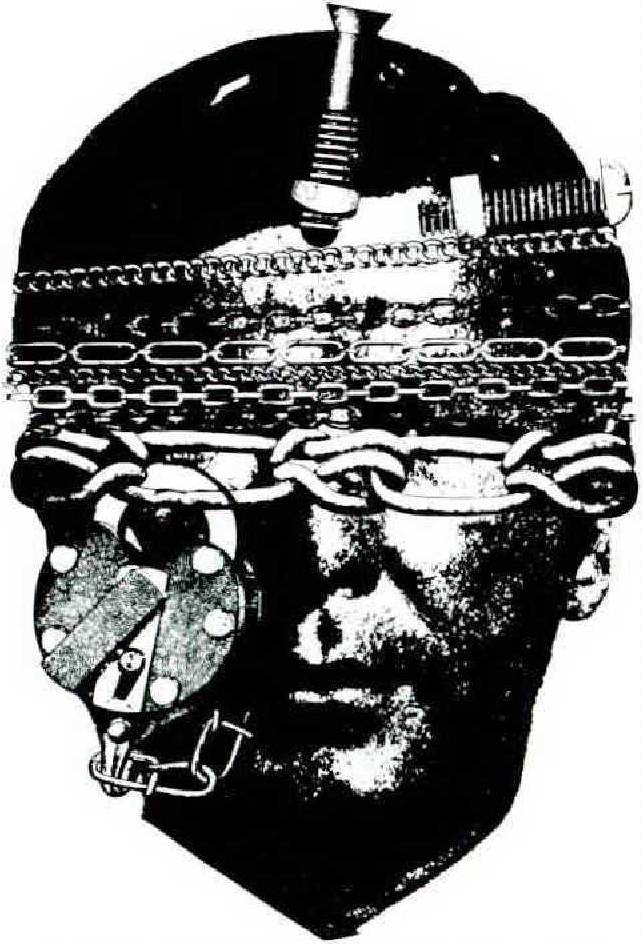

But how many of the words we use are as meaningless, either because they were not accurate in the first place, or because they have lost any precision that they once had? The question is important because the American sociologist who said that words use us at least as much as we use words was right. Our words do much of our thinking for us; we are necessarily manipulated by them.

Let me begin with three words or terms that clearly do manipulate the way in which we think, that create the kinds of stereotypes of which Walter Lippmann wrote in Public Opinion, and become fixed in our minds.

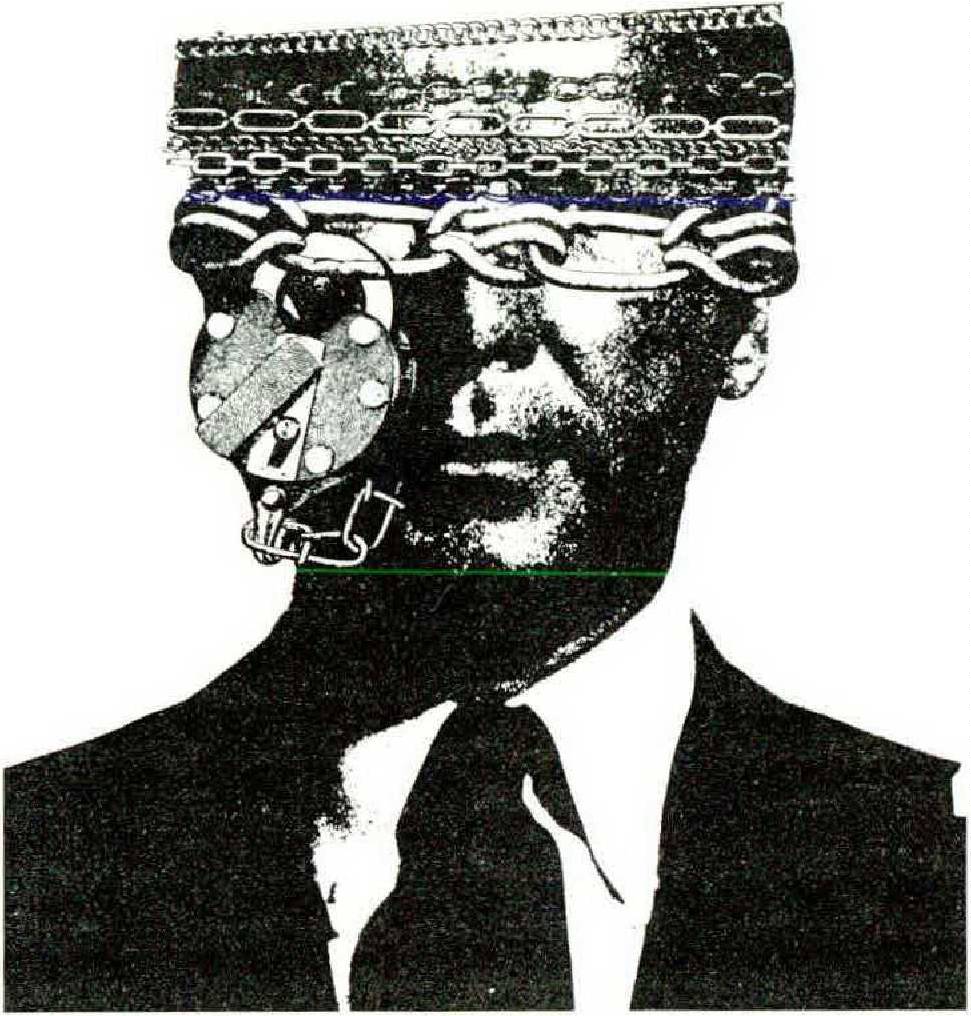

We are being manipulated, for example, when we talk of the black district of a northern city in the United States as a “ghetto.” It is no such thing, and by calling it a ghetto we make it more difficult for us to think. When was the word first used in this sense? Had something in fact happened that made it seem necessary and appropriate, and that can explain to us what it means?

Here is a quotation—the first journalistic reference to black ghettos that I have so far encountered in my reading—and I suggest that the reader try to give it a date, at least to place it in the right decade:

The Washington Correspondent of the Times says in Tuesday’s paper that a curious new phase is appearing in the Negro problem in various northern cities. The more prosperous Negroes have gradually acquired dwellings in the better residential quarters of the towns, and the whites resent this, as they say that in consequence these quarters degenerate. A crisis has been reached at Baltimore, where the City Council is said to be about to pass a measure segregating the coloured people in certain parts of the town. In New York residents and property owners have combined privately to exclude coloured people from at least one district. The correspondent doubts whether the measure proposed at Baltimore would be constitutional. Apart from that it is felt that the establishment of the Ghetto system would greatly complicate the race problem and hinder the salvation of the coloured people.

The 1940s? The 1920s? Actually, the reference is to The Times of London; the quotation is taken from the English political review, the Spectator; and the date was March 25, 1911.

“Ghetto” ought properly to refer to a quarter of a city to which a group, historically the Jews, is restricted by a positive law. To this extent, the use of the word by the Spectator could be justified, since it referred to a proposed ordinance of a city council. But by the time of the race riots of the early 1940s the use had become polemical. “The Negro, imprisoned in the ghettos of the American cities,” was a characteristic use in Politics in August of 1944, and it is this current polemical use which is given as the second definition in the American Heritage Dictionary: “A slum section of an American city occupied predominantly by members of a minority group who live there because of social or economic pressure.”

There is no mention of confinement, of positive law and legal enforcement, and one must ask whether our thinking, and our opportunity to see and act clearly, are improved by such a slackness in our language.

I deliberately say our “slackness,” and not our “misuse” of the language. Although there is considerable misuse, it is dangerous to lean too heavily on it. Our language must change, which means that the uses of words will change; and it is often difficult to tell what is legitimately a new use and what is illegitimately a misuse. But we can try to make sure that there is no slackening of the language; and the use of “ghetto” when it does not refer to confinement by positive law is exactly the kind of slackness in language that leads to a slackening of thinking.

After all, the second meaning in the American Heritage Dictionary raises all kinds of questions. What it seems to tell us is that a comparatively prosperous neighborhood with a predominantly black population is not a ghetto; only a slum is. But what is a slum? One turns the pages of the dictionary to find only one definition: “a highly populated urban area characterized by poor housing and squalor.” The word “characterized” is sloppy—surely the whole point of a properly considered definition is to make it unnecessary for us to speak vaguely of what “characterizes” something—but no matter. What intrigues me is that there is no mention of the poverty of the inhabitants. If the area had poor housing and was squalid, but its occupants were not poor, would it be a slum? Some of the communities of “hippies,” many of whom are not poor, and the “poverty” of whose condition is not usually enforced, would by this definition be slums.

I do not intend to rest much of my argument on dictionaries, although they are (or ought to be, if they are good) our first and last resource. But it may be worthwhile, in this first example, to demonstrate that even a close reading of dictionaries is not picayune, or what is popularly but wrongly called “merely semantics.”

In the A-G Supplement of the OED, the new use of “ghetto” is given for the first time, but it is described as transf.—a transferred sense, and fig.— a figurative use. That already tells us something about how we are using the word. The definition then follows, but it should be noted, as one reads it, that it in fact includes three definitions, each different, and each more vague than the previous one: “2. transf. and fig. A quarter in a city, esp. a thickly populated slum area, inhabited by a minority group or groups, usu. as a result of economic or social pressures; an area, etc. occupied by an isolated group; an isolated or segregated group, community, or area.” By the end, one is being very figurative!

But what of “an area, etc., occupied by an isolated group; an isolated or segregated group, community, or area”? Does this mean that a ghetto need not be urban, need not be a slum, need not be inhabited by members of a “minority” group who are poor, need not be characterized by poor housing and squalor? By this definition, the survivors of the Highland crofters in Scotland, for example, must be held to live in a ghetto, although they are scattered across the glens, for they certainly are “isolated and segregated.” One cannot help wondering, was Brook Farm a ghetto? is a monastery a ghetto? and so on. How transf. and fig. can we allow our use of the language to become?

Let us take another example. “These groups … we have called ‘ethnics.’ ” When did that sentence appear, using the word as a noun, and placing it in quotation marks, as if announcing a new coinage?

It is to be found in the first of the studies of “Yankee City” by W. Lloyd Warner and Paul S. Lunt, The Social Life of a Modern Community, published in 1941. (The first reference given in the A-G Supplement of the OED is also taken from the “Yankee City” series, but from a late volume that was published in 1945 by Warner and Spole—who was by then Warner’s collaborator. I have to admit that to find an earlier use of a word than that given by the OED is almost more satisfactory than to be cited by it.)

Thirty years earlier, Warner and Lunt would have spoken of “hyphenated Americans,” or of one of a score of similar terms that were used at the beginning of this century; thirty years later, “ethnics” leaped into the political vocabulary, immediately to become the code name for a stereotype. It is interesting that Warner and Lunt coined their term only two decades before Daniel Patrick Moynihan and Nathan Glazer wrote Beyond the Melting Pot. If the “melting pot” had completed its work, or almost so, there would have been no “ethnics,” or only relics of them, on which to fix the label in the late 1960s. It is to this kind of consideration that we are forced if we search the language of politics for its meaning.

“Ethnics” is a wholly different term from “ethnic group,” which is merely descriptive, no more polemically suggestive than a statistic in a census. One belongs to an ethnic group, one is an ethnic, and there is a world of difference. To say that someone is a member of an ethnic group is implicitly to say that one is describing only one of his characteristics. To say that he is an ethnic is to imply that this is the most important characteristic about him, the determining characteristic; and we begin to think in this way for no better reason than that this is how the word makes us think.

A Polish-American who is a Catholic who is a wage-earner who is a Democrat who lives in Cicero and is many other things as well—he is also an individual—cannot be reduced to any one of these. He is himself a coalition, of interests and aspirations, as the groups to which he belongs are coalitions. The fact that he is of Polish extraction—even the fact that he is white—may be less important than the fact that he is a wage-earner. This was not understood, for example, by George Wallace in 1968, when he appealed to the northern white worker almost solely on the “racially” loaded issue of “law ’n’ order.” On the issue of race, he could appeal to the “ethnic,” who as an “ethnic” responded. But when the trade unions and the Democratic Party at last moved, to repel Wallace as much as to repel Nixon, they appealed to the wage-earner, and it was the wage-earner who responded, so that the support for Wallace was, within a month or so, cut by a half.

If the “melting pot” had completed its work, there would be no “ethnics.”

The idea of the “ethnic” was one of the faults in all the attempted descriptions of a “real majority” or an “emerging Republican majority” which were showered on us between 1968 and 1972, and which now look as insubstantial as in fact they were. But all that I am seeking to establish at the moment is that this powerfully manipulative word was the invention of two academic sociologists, then misleadingly imported into the actual world of politics.

Now to take a third example. The phrase “Middle American” was first used, as far as I know, by Joseph Kraft in the spring of 1968, when he was writing about the municipal workers in New York City who were enraged at the administration of John Lindsay. He specifically referred to their ethnic character: Irish policemen, Italian sanitation workers, Jewish schoolteachers, and so on. Since then, the use of “Middle American” has so broadened that it now means almost anything that anyone wants it to mean. Even oil men and bankers in Texas can be heard calling themselves “Middle American.”

It has also been used as if it were synonymous with the phrase “silent majority”—although we heard less of the majority’s silence once it had spoken, like the apprentice, against its sorcerer—and what is at work in the two phrases is one of the most persistent concepts in the political language of the United States, in this century at least. What is being resurrected in such parlance is the idea of the “forgotten man.”

“The Forgotten Man”! We all know who coined that phrase: William Graham Sumner, in 1888, as a part of his attack on state intervention for the purpose of social reform, on the idea that, as he put it,

A and B decide what C shall do for D … In all the discussions attention is concentrated on A and B, the noble social reformers, and on D, the “poor” man. I call C the Forgotten Man … worthy, industrious, independent, and self-supporting … not technically “poor” or “weak” … minds his own business, and makes no complaint. Consequently the philanthropists never think of him, and trample on him.

The first President to use the term was Franklin Roosevelt; but he represented the A and B of Sumner, supposed to be the enemies of C in their concern for D. The phrase was the same; the idea had been transposed.

But perhaps the most astonishing alliance with the “forgotten man” was proclaimed by none other than H. L. Mencken, the scourge of the “booboisie,” in the first number of the American Mercury in 1924, when he said that the reader whom its editors “have in their eyes, whose prejudices they share and whose woes they hope to soothe is what William Graham Sumner called the Forgotten Man—that is, the normal, educated, well-disposed, unfrenzied, enlightened citizen of the middle minority … these outcasts of democracy.” The phrase was in this instance given a third meaning.

The fascination of Mencken’s definition is that such an exclusiveness is given to what was intended, by Sumner at least, to be an inclusive concept. The “forgotten man” was to Mencken not the “Middle American” or the “silent majority,” but, as he put it, the “middle minority”—all of which suggests that, when we use phrases such as these, we may be talking about nothing except what we think we are talking about; and that we will know what we are talking about only when we give our attention, as Confucius bid, to the “rectification of names.”

“Middle American” now means almost anything that anyone wants it to mean.

But let us look at another word that has already crept into at least three of the definitions that have already been quoted, and which can sneak past us because we are so familiar with its sound that we imagine we are familiar with its meaning. In their definitions of “ghetto,” both American Heritage and the OED referred to “minority groups”; Mencken referred to the “middle minority"; and at once we confront one of the strangest changes of meaning in the vocabulary of politics that has taken place in recent years.

By “minority” today, we mean a disadvantaged group of citizens. The two most prominent “minorities” in our conversation are blacks, who number more than twenty million, and women, who number more than one hundred million. In other words, more than three fifths of the population of the United States is composed of the members of two minorities. Swift would have laughed.

Fifty years ago, when Ortega y Gasset wrote The Revolt of the Masses, “minorities" meant the privileged few at the top: “… the masses are today exercising functions which coincide with those which hitherto seemed reserved to minorities; … these masses have at the same time shown themselves indocile to the minorities … the life of the ordinary man is today made up of the same ‘vital repertory’ which before characterized only the superior minorities.” One must emphasize that this was then the normal way in which the word was used. The “minority” was the “elite” opposed to “the masses”; and it was in this sense that Mencken spoke comfortably of the “middle minority.”

Today, by a “minority” we mean not the privileged at the top, but the underprivileged at the bottom. The change in the usage is intriguing; it tells us a lot about what has happened to our societies in the intervening years. The few used to be those who were allowed in; they are now those who are kept out. It is astonishing how flexible the vocabulary can be, how little we notice the changes in its usage.

I am not objecting to the new usage. I am merely suggesting that if we examine the vocabulary of politics, it can be informative. If we do not examine it, it will obscure; if we do, it can illuminate. It is, after all, extraordinary that in half a lifetime this word should have moved, without any of us registering even a hiccup when we use it, from the top of the social ladder to the bottom. Not only our thinking, but our actions as well, are affected by such changes.

This was vividly demonstrated at the Democratic Convention in 1972, when the proportional representation of “minorities” in the new sense of the term was a fetish. As one gazed at the delegates, however, one realized that the effect of the changes was not as simple as that, and that the McGovern Rules had produced a convention that was composed not only of the new “inferior minorities,” to adapt the phraseology of Ortega, but also of the new “superior minorities.” It was a convention of “minorities,” the affluent as well as the poor, because that was how the makers of the rules were thinking.

I think it is important to understand this. For why should one be surprised that rules that are designed to favor some minorities, enabling them to capture a ward meeting or a convention, will work also to the advantage of all minorities, the privileged few as well as the unprivileged few, to the exclusion of those who are neither fortunate enough to belong to the first nor unfortunate enough to belong to the second, and are thus rudely transformed into an unprivileged majority?

Those who talked of “minorities” in the new sense were in fact making the same mistake as those who spoke of “ethnics,” identifying an individual or a group by one of his or its characteristics, which was taken to be determining: If one is a black, one feels and thinks and votes only as a black; if a woman, only as a woman. The effect, if not the intention, of this way of speaking must be to single out—mark off—one individual or group from another; in short, to “polarize,” and with that word, we are face-to-face with another new entrant into the language of politics.

Not long ago, Annie Gottlieb wrote of “that charade we called ‘polarization’ (in which the media played the master of ceremonies, handing out the stereotypes)”; and her description is accurate, although one is tempted to point out that “media” is itself a code name for a stereotype. (“Media” suggests that there is no difference in purpose and function between print journalism and television journalism; that within print journalism there is no difference in function and purpose between Time and the New York Times. It lumps together different activities, usually for the purpose of condemnation. Enemies of journalism, such as Spiro Agnew, refer to the profession as the “media” in disdain.) The rapidity with which the concept of “polarization” entered the language of politics, then to disappear from it as rapidly, was astonishing to watch. Someone had only to use the word—for that is all that it is; and I have not tracked down who was responsible—and at once it was assumed that there was something actual somewhere that it represented. One could even see columnists and reporters going in search of “polarization” in much the same spirit, and to much the same effect, as Pooh going in search of the Heffalump: round and round they went, all the time following their own spoors.

All the words that I have mentioned so far have had the same effect. It is not only that they simplify what is complicated, but that the particular way in which they do so is disturbing. The tendency of all of them is to isolate what has relations, to segregate what is not apart. Thus, “ethnics” are separated from nonethnics, “Middle Americans” from other Americans, “minorities” from the majority; the words themselves put people in “ghettos,” and freeze them at opposite poles. It is in this way that we are manipulated by the words that we tolerate and use.

In politics the conversation of a society is most readily brought to focus, and it is not surprising, therefore, that politics will draw much of its language from outside its own activity. It used to be influenced by the language of theology; the examples that I have given suggest that it is today greatly influenced by the language of sociology. It will always be considerably influenced by the language of law, the language of the military, and the language of commerce. It is only rarely that politics is itself the creator of “names”; and that is why we must be careful when the conversation of politics, and through it, the language of government, adopts the vocabulary of sociology or science, business or the military, where it may have some exactness, and makes it an instrument of generalized persuasion and command.

For example, I recently found a new coinage in commerce: “de-marketing.” It leaped to my eyes as I opened the Houston Business Chronicle of April 8, 1974, in the headline: “Oil Company Execs Debate ‘De-marketing’ Dilemma,” reporting a two-day conference, from which the press and the public had been excluded, of twenty-five executives from fourteen major oil companies, whose twin concerns were “marketing and public affairs.” One need hardly say in passing that “public affairs” is a euphemism for “public relations,” which is in turn a euphemism for public advertisement.

Gabriel Gell, the president of a corporation that goes under the name of Gasoline Marketing Trends, said that the term “de-marketing” was used to point out “how allocation of scarce resources has changed the meaning of the word ‘marketing’ from increasing demand to satisfying demand. As a result of product shortages, marketing is now a system for controlling the level and composition of demand.” One is grateful to him for his candor, and to the reporter, Deborah Kaiser, for making public his definition.

For what he points out is that “de-marketing” is still “marketing”; and that “marketing” is a “system for controlling” the market. In short, a word is created that says the opposite of what it would appear to mean. (It reminds one of Talleyrand’s famous remark that “non-intervention” is a word that means much the same as “intervention.”) If “marketing” is a system for controlling the market, “de-marketing” ought to mean the abandonment of that control; instead we find that it means the retention of it. This was apparently made clear by the executives of the oil companies in their discussions. Although they were uncertain about the future, they were at least generally agreed that there are now too many service stations for all of them to be operated at a profit, that the stations ought to be operated by the oil companies, and in particular that the oil companies ought not to hand over the distribution and retail sale of gasoline to any third party, such as Sears or Montgomery Ward.

Now, it does not disturb me that commerce should invent a word like “de-marketing.” My concern is that the word will travel from Houston to Washington, from the language of commerce into the language of politics, and so into the thinking of government as it determines its policies. Our past experience suggests that this may easily happen: that the word may journey from the oil companies to the government departments and congressional committees with which they deal, from there to the business pages of the newspapers, from there to the editorials, from there to the columnists, from there to the television commentators; and in the end we will all talk of “de-marketing” as if it is real and new, and means something other than the traditional system of controlling supply and demand in the interest of private profit.

The lexicographers at Oxford might well jot down the word now for their next A-G Supplement, fifty years hence, and note its origin. Gabriel Gell of Gasoline Marketing Trends may yet be a locus classicus.

It is not only the language of commerce that may be absorbed too easily into the language of politics, but that of any interest. The vocabulary of Ralph Nader, for example, seems to me to require the strictest examination. My reading of it has so far been cursory, but it gives the impression of being slack to the point not only of unintelligibility, but even of deception. It is a fact that “consumerism” and “environmentalism” have their own jargon, which they use to the same purpose as their enemies, to prevent us from thinking for ourselves, to persuade us not to examine what they are saying, to jerk us by words that will trigger a response, no less in a “good cause” than in a “bad cause.”

We may rightly be appalled when John V. Neeson, of Neeson International Corporation, San Francisco, says in 1972: “The thing in Vietnam is really winding down.” A war—“the thing”! “Winding down”—when it is still going on! What could be more typical of the language of public relations? Yet it is no worse than the claim that in the conduct of the war the United States was guilty of “genocide.” In both cases, words are being used to evade the realities of the situation, deliberately to obfuscate them, so that we do not deal with them.

It needs to be made clear that the politician is entitled to his language, as long as it is his. This is a point that was missed by George Orwell in his essay on the political debasement of the English language. I have never been impressed by that essay: His essential comparison—such as rewriting a passage from the New Testament as a politician might today phrase it—is false. Politicians are not a committee of theologians writing a King James Version of a Holy Scripture. Language in politics is not intended to serve the same purposes as language in poetry, for example, and it is facile and misleading to suggest that they can be compared.

I have said that politics is the focus of the conversation of a society, and this conversation is composed of many voices. There are the languages of the law, of science, of commerce, of the military, of poetry, of philosophy, and so on, as well as the language of politics. Above all, there is the language of unknowable numbers of ordinary people, each translating his everyday experiences into his own everyday speech, distinct even from that of his neighbor; and this language can never be properly known or retold precisely because it is, for the most part, individual and unrecorded. One of the claims that can be made for the politician is that he, more than anyone else, must listen to, and will be affected by, all the other voices that contribute to the conversation of the society, so that his language can never be like any one of theirs, and will often, if it is allowed to be slack, not seem like language at all—the condition today against which I am complaining.

“Public Affairs” is a euphemism for “public relations,” which is in turn a euphemism for public advertisement.

It is the task of the politician to persuade people to do things—or to be content not to do them, which is the same thing, and he must therefore be allowed to use his own language to this end. In much the same way, the law is entitled to its own language in its task of interpreting generalized rules in their application to individual cases, and science is entitled to its own language in its task of constructing models by which to try to understand the universe. Poetry also makes its own use of language, at once the most exact and the most ambiguous.

The language of the one cannot be judged by the lights of the other. “Make the world safe for democracy” is an arrangement of words to which the philosopher or the poet would find it difficult to give a meaning. But to deny that it has a meaning, in the context in which it was used, is to deny the activity of politics, and therefore the validity of its own language. Within its context, the phrase is intelligible. The promise that is made, the hope that is raised, can be understood; it can be rejected as clearly as it can be supported.

But this is not true if troops are called “advisers,” if plans to make war are called “scenarios,” if an invasion of Cambodia is called an “incursion,” if bombing is called “air support.” One or more of these terms were part of the vocabulary of three administrations as they went to war, and what is important is that it was a vocabulary that the politicians took from elsewhere, and which the political journalists also used.

When one reads the New York Times and other newspapers from 1961 to 1967—when the American press in general was, by and large, supporting American participation in the war in Vietnam—what is striking is that the journalists used, without questioning, the language of the men of power. The whole language of games theory, which obsessed the Department of Defense at the time, and so misled two administrations, was taken over by the journalists: the whole insane vocabulary of “scenarios” and “options” to describe plans to send some men to kill other men. The war was conducted not in secret, but in jargon.

Moreover, this jargon was taken from a field that was not political, and not even military. Games theory was essentially an academic enterprise. Even as such it was mistaken, but that is beside the point. What matters is that a model was constructed, according to the assumptions of the theory, by which it was said that the behavior of men, individually and collectively, could be simulated and predicted. It was assumed that the reactions of men or of nations to any situation could be enacted in a sandbox, and the lessons of the sandbox could then be enacted in real life. But this is exactly what the true politician knows to be untrue. He knows that the affairs of men are not tidy, and cannot be tidied; that the only rule that can safely be followed is a kind of rule of thumb; that one is always on a raft, as the eighteenth-century American conservative, Fisher Ames, said of democracy: “It never sinks but, damn it, your feet are always in the water.” The language of politics will always be most accurate when it takes this untidiness into account; it must be a language of shifts.

The language of politics, in short, must reflect the activity of politics. In circumstances that shift, it must find the grounds on which action is possible. This is the predicament of the politician, and when he overcomes it, his language will be found to have its own strength. An outstanding example was provided in recent years in the major pronouncements of Lyndon Johnson on civil rights. One could watch him as he drew together, speech by speech, the shifting bodies of support that he anxiously needed: at first to conjure them into place; in the end to command them.

The Department of Defense can give no adequate definition of “national security.”

There were passages addressed to his fellow southerners, to many of whom he knew he would appear a traitor; passages addressed to Congress, and specifically to Everett Dirksen, appealing above all to the sense of opportuneness that is always a motive force in getting Congress to act; passages in which he enrolled the flagging enthusiasm of the old New Dealers and the new enthusiasm of the younger liberals as he widened his attack and spoke, again and again, of “that one fifth of the people of the United States” who were denied the benefits of its citizenship. Each speech was like a quiver full of arrows, directed at different people and groups.

The language of command, when it came, was never anything but political; one can sense his awareness (as in the best speeches of Franklin Roosevelt) that he was addressing a coalition that might at any time dissolve, in a situation that might at any time change. Yet there was one more factor that was at work. Not even the severest of his critics, as far as I know, has ever questioned the sincerity of the stand that he was taking on civil rights; and anyone who ever spoke to him knows that his conviction—his conversion, if one will—grew out of an experience that was personal, genuinely and deeply so. The man was at one with the politician: they were conjoined.

It is this conjunction, of the man with the politician, that one always knew to be lacking in Richard Nixon, and the lack was in the end wretchedly confirmed for all to see. The peculiarity of him was that there seems to have been nothing in him between which the conjunction could be made; both the man and the politician were lacking. When one combs the “language of Watergate,” the language that was used between Richard Nixon and his advisers, what I think will be found to be most revealing is how unpolitical was its nature. One finds in their language no awareness that men of different persuasions and different interests must and can be brought together on some common ground where they may meet honorably and candidly, nor that if one is to use the language of command, it can issue only from a genuine respect for the political process, and that this respect must naturally be expressed in a language that is appropriate. Above all, what is lacking is a politician’s conviction in his own values, so that the language that he uses will bear the mark of his own personality, even as it bears witness to the truth of his own realized experience.

It is no accident, it is not trivial, that the phrase “at that point in time” so quickly became an early trademark of the whole Watergate affair. It caught on not only because of its illiteracy, although that counts, not only because of its prevalence in the Nixon White House, but because of the unconsciousness of its use, which suggests, as does the rest of the evidence, that no vocabulary as such was ever questioned in the White House as long as one could get by with it; and the slackness of their language in fact enmeshed those who used it as much as those whom it was intended to enmesh. To this extent many who spoke it, especially the more junior staff-members, knew not what they did.

Their use of the language never prompted them to ask. A committee of the National Council of Teachers of English, which is investigating the use of language by public officials, has found that the Department of Defense could give no adequate definition of “national security.” This is at least as important as the fact that Nixon and his advisers were willing to reach to “national security” as a defense of their actions. The phrase was available, imported into the language of politics and used by almost all of us at some time or another in the past thirty years.

One can give a meaning to “national defense”; one can give no meaning to “national security,” with the result that one can give any meaning to it that one likes. Yet the phrase lies, not only in the speeches of politicians and the editorials of journalists, but in laws of Congress and in the judgments of courts. This is the kind of clearing up that the language of politics now requires.

I have tried to suggest here how far and deep the clearing will have to reach, and how necessary it is that the clearing be done with a true understanding of, and respect for, the activity of politics. That the rectification of names is the business of government is not an easy concept for us, since it owes a great deal to the Chinese (and Confucian) idea of the role of government: that it will to some extent be the arbiter of men’s manners as of men’s thinking. But the more one considers not the obvious lying of the past two years, but the much more general feeling of deception, sometimes called the “credibility gap,” which has been felt for too long, the more some rectification seems to be urgently needed. It is the failure, on the one hand to use the language exactly, on the other to examine it rigorously, that is the cause of the malaise; in good causes as well as bad.

It seems worth adding, as a postscript, a famous passage from a speech Charles James Fox made in the House of Commons on February 5, 1800, when the Younger Pitt had said that Britain must pause before agreeing to negotiate with Napoleon:

Gracious God, sir! is war a state of probation? Is peace a rash system? Is it dangerous for nations to live in amity with each other? … Cannot this state of probation be as well undergone without adding to the catalog of human sufferings? “But we must pause!” What, must the bowels of Great Britain be torn out—her best blood spilled—her treasures wasted—that you may make an experiment? Put yourselves—oh! that you would put yourselves in the field of battle, and learn to judge at the sort of horrors that you would excite …

… if a man were to present now at a field of slaughter, and were to inquire to what they were fighting—“Fighting!” would be the answer; “they are not fighting: they are pausing.” “Why is that man expiring? Why is that other writhing with agony? What means this implacable fury?” The answer must be: “You are quite wrong, sir; you deceive yourself—they are not fighting—do not disturb them—they are merely pausing! This man is not expiring with agony—that man is not dead—he is only pausing! Lord help you, sir! They are not angry with one another; they have no cause of quarrel: but their country thinks that there should be a pause. All that you see, sir, is nothing like fighting—there is no harm, no cruelty, nor bloodshed in it whatever; it is nothing more than a political pause.”

But then, Fox did not have a speech-writer.

Copyright © 1974, by The Atlantic Monthly Company. Boston, Mass., 02116. All rights reserved