The Magical Thinking of Joan Didion’s Estate Sale

Mythology came long ago for the celebrated writer; now it’s coming for her belongings.

On the evening of December 30, 2003, Joan Didion and her husband, John Gregory Dunne, decided to stay in. Didion made a fire—a habit from their years in California, where, late in the day, the coastal fog creeps landward—and then dinner. They ate in the living room, as they usually did when it was just the two of them, at a small table set near the fireplace. They were discussing the scotch that Dunne was drinking, maybe, or World War I; Didion couldn’t quite remember. What she did remember, though, is what happened after Dunne, in the middle of the meal, collapsed: the silence, the panic, the paramedics, the defibrillator, the doctor, the priest. The fact that, as they had their dinner that night, “John was talking, then he wasn’t.”

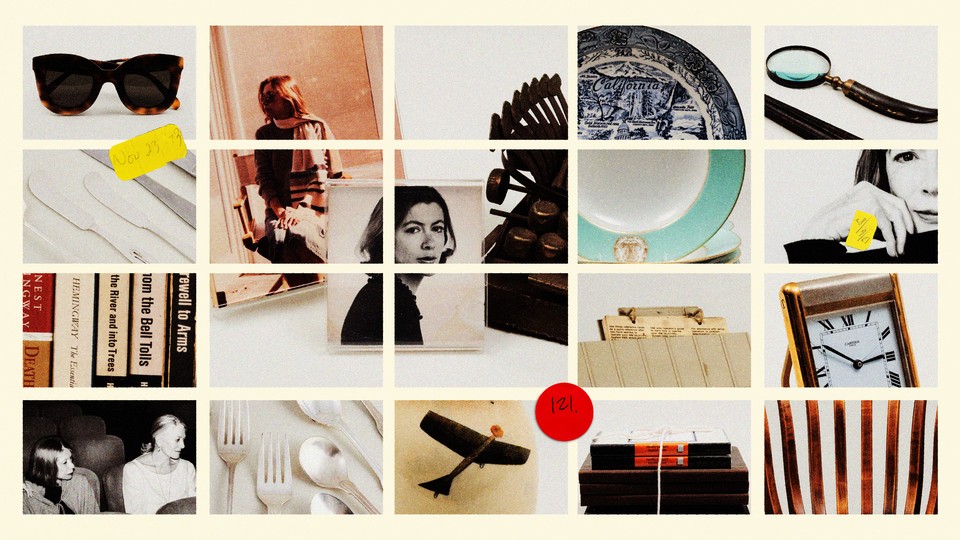

The table where Dunne fell, with its spindly legs and folding leaves, features prominently in The Year of Magical Thinking, Didion’s memoir about Dunne’s death and her attempt to find coherence in her grief. The table is also now for sale: It is one of the more than 200 items from the couple’s New York City apartment being auctioned after Didion’s own death last year. The auction house, Stair, describes the table—listed as a “Late Regency Ebony Inlaid Mahogany Pembroke Table”—as having “staining, fading, gouges and scuffing throughout, particularly on the top,” adding, “It was at this table that John Dunne suffered the fatal heart attack that took his life.” Its estimated value is $1,000 to $1,500.

The famous are, in that way, ordinary: Death’s sour pragmatisms will come for us all, emptying our homes and distributing our things and selling the scenery of our lives, eventually, to the highest bidders. The difference here is that the scuffs and scars on the things Didion left behind will only bolster their value. You can’t talk about Didion the writer without also talking about Didion the myth—or without noting that the two figures, by the end of her life, had become nearly indistinguishable. She was sometimes described, with only some irony, as a saint, her fans as a cult. The list she used when packing for reporting trips (clothing, underwear, cigarettes, Tampax, typewriter) has taken on talismanic dimensions. The auction, which goes by the name “An American Icon” even as it sells Didion’s paper clips, brings an apt literalism to all the lore. In the process, it makes a claim fit for a writer who so deftly punctured our national fictions: You can, it turns out, put a price on mythology.

In writing, Didion once remarked, “the last sentence in a piece is another adventure. It should open the piece up. It should make you go back and start reading from page one.” The objects of the sale are, in that sense, epitaphs. They open up the life of a person whose public image involves oversize sunglasses and wary scowls and other light armors of cool. They suggest that Didion, under all the gauzy iconography, also possessed that most modern of currencies: relatability. They range from large pieces of furniture to framed pieces of art to lightly stained napkins. The sale includes cookware and flatware. It includes a box, mustard-colored and slightly crumpled at the corners, of 12 Pilot Precise V7 rolling ball pens. The current bid for the box, part of a lot categorized as “Writing Ephemera From the Desk of Joan Didion,” is $1,100. By the time the final bidding closes on November 16, it will likely be much higher.

The belongings of celebrities, sold and bought in this way, require their own strains of magical thinking. Their value is partly pragmatic—the proceeds from Didion’s estate sale will go to a writing scholarship and to Parkinson’s research—but largely spiritual, derived from a primal fact of the human animal: our need for enchantments, our hope that small gods walk among us and that their divinity might, with the right offerings, be made transferable. One of the lots is a collection of Didion’s notebooks. The books are blank. This is the alchemy at work.

The sale’s offerings become implicated, in that way, in one of Didion’s most celebrated insights: that we tell ourselves stories in order to live—and that the condition is our curse as well as our blessing. Maybe she looked at the notebooks and thought of a new way to say something. Maybe she opened one of them, Pilot pen in hand, only to close it unmarked. The books’ new owners will append the stories that suit them. The same is true for one of the more delightful items in the collection: an apron that reads Maybe Broccoli Doesn’t Like You Either. The object does not match the iconography, and the dissonance beckons. Did the woman who turned aloofness into an art form really cook dinner in a novelty apron? Did she buy it herself? Did she receive it as a gift? (Did she, upon seeing it, consider the possibility of insouciant crucifers and laugh at the thought?) Did the thing mean something to her, and is it therefore more than a thing?

Authors can act as their own works of literature; they can inspire analysis and interpretation. Didion’s fame rose at a moment that found fandom evolving from a condition into an action—a time when loving someone publicly often meant collecting detailed knowledge of their life. The Didion auction embraces those forensics. It invites voyeurism. It suggests what Didion often talked about explicitly: Authorship is a tangle of control and concession. It is omnipotence, until it is the opposite.

Celebrity works that way too. “Want a piece of Joan Didion?” one headline about the auction reads, giving up the ghost. The large sunglasses—a pair of which are now on sale—that were so much a part of Didion’s brand doubled as a defense: Didion wrote in 2011 that she had loved them since she was a girl, when she would imagine herself as a glamorous divorcée “wearing dark glasses and avoiding paparazzi.” That dual desire—to be seen and hidden, to be at once on the stage and in the rafters—was part of the allure. She was reluctant. She was insistent. She was painfully shy. She was singularly bold. She traveled around and made her claims about a land of impatient dreams; her fans, in turn, claimed her.

Didion’s fame-making essay collection, Slouching Towards Bethlehem, borrows its title from William Butler Yeats’s poem about collapse, and that sense of dissolution is her writing’s most urgent theme. Things are always falling apart. They are always threatening to. But objects, whether tables or notebooks or aprons, can be tethers—to the past, to the stories people have told, to coherence. Didion, as a writer and a person, is often associated with detachment: Didion the anthropologist, Didion the diagnostician, Didion the cool, Didion the cold. But the goods of her life, offered up as goods for other people’s lives, are reminders of another dimension of Didion’s work: her need, frank and achingly relatable, to be understood. Didion named her final book Let Me Tell You What I Mean. She often acted as her own Greek chorus, interrupting her story to explain herself. “I want you to know, as you read me,” she wrote in an early essay, “precisely who I am and where I am and what is on my mind. I want you to understand exactly what you are getting.”

The objects of her life serve that understanding. They offer revelations about Didion the person and Didion the ongoing story. They are reality and myth, colliding and colluding—each unimaginable without the other.