The Man Working to Keep the Water On in Gaza

How one engineer in Gaza is trying to protect his family and his community at a time when water is running out

Numbers are one way to make the destruction of war legible: number of hostages, number of children killed, number of buildings destroyed, number of aid trucks that made it across the Egyptian border. For Marwan Bardawil, who lives in Gaza, the unit of peril he tracks is cubic meters per hour. Bardawil is a water engineer with the Palestinian Water Authority overseeing Gaza. And these days he is measuring, in cubic meters per hour, the quantity of water flowing through the pipes that, in prewar time, carried 10 percent of Gazans’ drinking water—pipes that are controlled by Israel. Right now, with other water sources dwindling, those pipes are Gaza’s lifeline. “The people are really in need of each drop of water,” he told me.

For the past week, I’ve been checking in with Bardawil every day as he struggles to find clean sources of water. (You can hear our phone conversations on this week’s episode of Radio Atlantic). In the best of times, Bardawil’s job is difficult. Gaza sits between a desert and the Mediterranean Sea, so groundwater must be pumped from an aquifer. After years of overuse, even before the war began, 97 percent of the aquifer water didn’t meet quality standards from the World Health Organization. Making it safe to drink requires fuel, which isn’t abundant in Gaza. The other major reliable source of clean water is those pipes, three in total.

In other words, the water supply in Gaza was already fragile even before the October 7 Hamas attack on Israel. Overnight, as Israel’s retaliatory bombing campaign began, the fuel required for water desalination became very scarce. Israel controls the flow of materials in and out of Gaza, and fuel has many potential wartime uses. Bardawil, meanwhile, kept his eye on those pipes. That first day, he called the engineer who was monitoring the central computer. Within two minutes, the cubic meters in all three had dropped down to zero.

Sometimes neighbors show up at the apartment he is renting in South Gaza with his wife, children, and grandchildren. They figure that because he is Gaza’s water man, he must have some magic source of water he can tap. But this isn’t true. In fact, over the past couple of weeks, Bardawil himself has gone three stretches with no running water at all—just a couple of water bottles to share between the six adults and two children in his household.

“We are not, you know, different from Israelis, Jordanians, Egyptians, Americans. And we deserve a life which is suitable for a human being,” he said. “We deserve a better life.”

Listen to the conversation here:

The following is a transcript of the episode:

Hanna Rosin: Nearly every day this past week, I’ve talked on the phone with a man named Marwan.

[Tape]

Rosin: Hello. Oh, can you hear me?

Marwan Bardawil: Yes. Hello.

Rosin: Good evening, Marwan.

Rosin: His full name is Marwan Bardawil. He’s 60 and he lives in Gaza, where the phone connection is understandably spotty right now.

Bardawil: The problem is that the networks are so weak.

Rosin: Marwan has a very specific job. He’s not a political or military figure. He’s not a foreign-policy expert or an activist. Marwan is an engineer, specifically a water engineer for the Palestinian Water Authority. And his job is to get water to the 2 million people that live in Gaza, which is hard, even in normal times.

[Music]

Rosin: Gaza sits between a dry desert and the salty Mediterranean, so they have to pump groundwater up from below. But over 97 percent of that water doesn’t meet the water-quality standards of the World Health Organization.

It’s often salty, brackish, or contaminated. The plants needed to clean that water require fuel, which is in very short supply right now. And the only other major reliable source of clean water comes from three pipes controlled by Israel, which, the day the war started, Israel turned off.

[Music]

Rosin: I’m Hanna Rosin, and for this episode of Radio Atlantic: my phone calls with Marwan as he tries to keep the water flowing in Gaza.

The humanitarian crisis there right now is overwhelming. The Gaza Health Ministry says more than 8,700 people have been killed so far. Food and fuel are running out. And if Marwan can’t get enough water to the right places, it gets much worse.

Bardawil: We are very close to a public-health disaster. And the number of impacted people will be huge, to the limit that the health authorities in Gaza cannot cope with.

Rosin: Without enough clean water, people get dehydrated, hygiene deteriorates, sewage backs up. Palestinians are already crowded into schools and shelters, seeking refuge from the war. Take away clean water, and soon cholera and other deadly diseases could spike.

[Music]

News tape: Israel has ruled out allowing basic resources or humanitarian aid into Gaza until Hamas releases the hostages it abducted during the weekend.

Rosin: In the days after Hamas’s terror attack, Israel cut off utilities in Gaza.

News tape: Israel’s sustained bombardment has now killed more than 1,400 people. Israel’s energy minister has insisted no electricity, fuel, or water supplies will be turned on until the hostages are home.

Rosin: So, when I began talking to Marwan last week, I wanted to know exactly what he saw at that moment.

Bardawil: One of the southern pipes goes down from 700 cubic meters per hour to zero. Other line—800 cubic meters per hour—goes to zero. The third one—1,400 cubic meters per hour—goes to zero.

Rosin: You could see that immediately?

Bardawil: It’s a matter of two minutes after they close it.

Rosin: With fuel about to be in short supply, these three pipes from Israel are Gaza’s lifeline.

Bardawil: This is the first time that they did such a thing, that they took a decision on a higher level, and which is not technical. That means it’s not a matter of hours or days. That means we have to look for managing the water without this source.

Rosin: But then several days later, one of the pipes got turned back on. It was a huge relief for Marwan. How or why they got one back, he’s not thinking about that. He’s just doing the math. Hospitals, houses, stores all need water. Two million people in Gaza need water. And one pipe is better than none.

Bardawil: I don’t want to imagine that this pipeline will be cut off again. I don’t want to have a nightmare while I am awake. What we have today is this pipeline is functioning as normal, and I hope that this will stay.

Rosin: At this point, it was Wednesday, October 25. And as we were talking, there was one functioning pipe. How many more days until there wouldn’t be enough clean water to go around?

Bardawil: At this hour, if things are remaining like this, after three, four days, the disaster is there.

[Music]

Rosin: A month ago, Marwan and his wife were empty nesters. Their son and daughter had both moved out, gotten married, and had children. They would visit at least once a week and occasionally take vacations together. Now, they’re all together in a small apartment in South Gaza. The kids are understandably confused.

Where did our old rooms go? Why can’t we take a bath every night before bed, like we used to? The answer is not so kid-friendly and runs through Marwan’s head all day: They have a little more than one gallon of water for six adults and two children. And that has to last for two days.

Bardawil: The first thing you stop doing is having a shower. You’re back maybe 100 years ago when there was no showers. And so on. You start to make the kids as the first priority, not you. So instead of drinking a lot of coffees and teas and other drinks, you stop doing that, or you do it once a day or twice a day. You stop cooking the type of food that consumes water.

[Music]

Rosin: Relatively speaking, he and his family are lucky. Marwan is able to pay for a private water company with a solar-powered desalination machine to fill up the building’s water tank once in a while. That is a luxury. When Israel started bombing Gaza, they told civilians in the north to move south, but about two-thirds of Gazans live below the poverty line. So unlike Marwan, many can’t afford to rent a temporary apartment in the south, much less buy private stores of water.

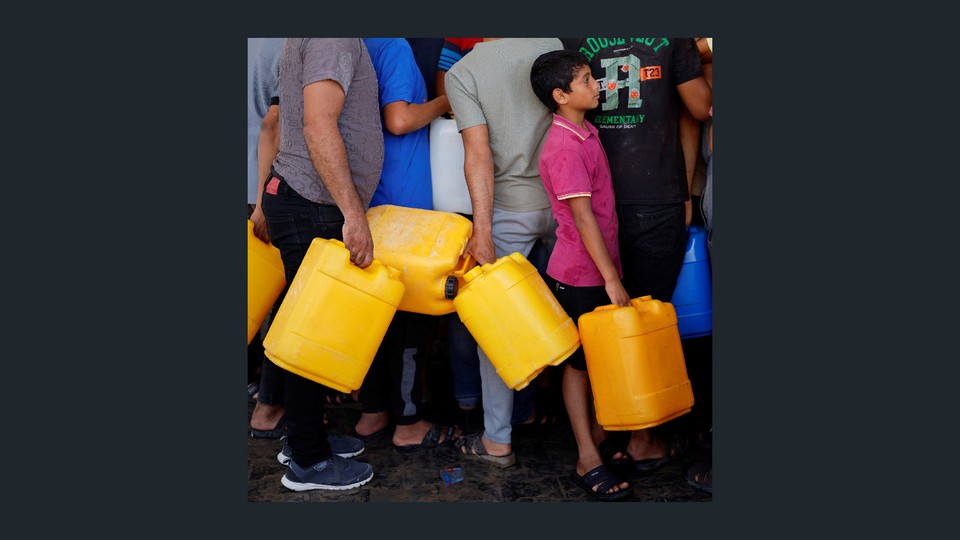

Instead, a lot of Gazans are cramped into makeshift shelters in schools and hospitals. The way they get their water is they walk for miles, looking for an open water station, and then carry those gallon jugs back to the shelter. Even before this war, the majority of Gaza’s health problems came from contaminated water. Marwan hears from his engineers in the field that skin diseases are already starting to show up at the shelters. That’s a first sign of worse problems to come.

Bardawil: Some civilians couldn’t find [water] to drink. Or they have very limited water to drink, or to clean the toilet after they use it. So there is a potential for insects to grow on the toilet. There is the smell, the gasses produced from the sewage.

Rosin: So, from the moment he wakes up, Marwan is on the phone to the Red Cross, to contacts in the West Bank, to engineers on the ground, to the UN, asking if there are any desalination plants working, if any pipes burst today. Should the water that day be diverted to the hospital? Or the bakeries? Or the shelters?

Now, every once in a while, people show up at his door asking for water. They figure he works in the water authority. He must have access to some magic tap that keeps the water flowing in his apartment at all times.

Bardawil: They think that, of course, you just make a phone call and the water comes, which is not the case.

Rosin: Marwan has actually seen his own water run down to zero. A water engineer without running water relying on a couple of ordinary water bottles.

Bardawil: In the last 20 days, more than three times we experienced a time with no water at all.

Rosin: And what happens on a day like that?

Bardawil: You’re nervous. You’re—it’s a hard day. It’s a very, very hard day. You cannot explain it. You cannot explain how you spend the time and try to use the minimum of the water.

Rosin: I call Marwan the next day. The math has accelerated.

Bardawil: Yeah. If you are talking about numbers, one day is passed, so it’s minus one. Yesterday we are talking about three days. Today we are talking about two days. Tomorrow we will talk about one day. And that’s it. It’s like you are running fast to the edge of a hole.

Rosin: That day started with a whole new problem: A pipe burst near a cluster of apartment buildings. An engineer in the field sent him a picture, which I asked Marwan to describe to me.

Bardawil: A street full of sewage. Like a small lake of sewage.

Rosin: And does someone live on that street?

Bardawil: Yeah, yeah. A street where people live, yeah.

Rosin: On a normal, non-wartime day, this is an easy problem. You call an emergency technician. They bring in a suction truck to clean up the mess, disinfect the area, and then replace the pipe. I asked him if he could do that now.

Bardawil: No, we cannot do anything. You cannot even reach the place. We just wait ’til it evaporates.

There’s nothing to do. It’s beyond your capabilities, beyond your control. You know that this will harm the people, but what we can do? Nothing.

And it’s not time to blame yourself, because what’s happening is much beyond us.

We as civilians, as pure technical people responsible for water, we just concentrate on providing water to the people, not more.

So, of course, we can fix engineering problems, but it’s not the right situation to think that way. We just hope that all this ends. And we hope that people and the civilians are not to be the side that loses everything—loses their lives, or their health.

[Music]

Rosin: Marwan sometimes goes to conferences with Israeli water technicians. They share a border, which means they share some other things, like an aquifer, runoff, and pipes. At these conferences, Marwan says the tone is pretty collegial. They speak technical English, trading tips about water management.

What’s unspoken is the power dynamic. Israel controls construction materials flowing in and out of Gaza, which are needed to repair and update these water systems.

Nothing comes in or out without Israeli approval.

Bardawil: And we, as technical persons, we just respect that this is the rule and this is the frame that we have, even if we don’t know exactly the reasons behind that. Sometimes it’s not understandable, so we do our best to do things the right way.

Rosin: Why do you respect the rule?

Bardawil: It’s not a matter of why. It’s a matter of you don’t have the choice. They are the controlling power.

Bardawil: I remember fishing with the other fishermen, watching them all the time, swimming, trying to learn riding the waves.

Rosin: He’s never taken his grandkids to that beach. It was highly polluted by sewage water and un-swimmable for years. Although, a year ago, after a massive international cleanup effort, Gazans did start swimming there again, and many reported that for the first time in years, the water looked blue.

I wanted to hear more about his childhood. But it was, by then, almost midnight Gaza time. Marwan was sounding tired, though he was too polite to say so.

Bardawil: We hope, pray every moment—not only for the people of Gaza, but for the people of all the regions—to have a normal, safe life.

Rosin: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

Bardawil: Which, look—by the way, after all these disasters, for more than 75 years, I think the time is now for solving this forever, not just a few years and then back again into the cycle, which if we will continue like this, there will be no end.

[Music]

Rosin: I said goodnight and take care to Marwan. I would talk to him the next day. But then when I called, I heard a recording.

Phone audio: “Marhaba. (Message follows in Arabic and then English.) “The mobile number you have dialed can’t be reached at the moment. You can leave a voice message by calling …”

Rosin: More from Gaza after the break.

[Music]

News tape 1: Good evening, and thank you for joining us. We begin tonight with a major escalation in the Israel-Hamas war and what may turn out to be the next phase in a long and grueling battle.

News tape 2: Israel unleashing massive wave of air strikes as it expands its ground operations in Gaza as well. (Explosion.)

News tape 3: Meanwhile, Gaza is facing a near-total communications blackout, cutting Palestinians off from the outside world and, of course, cutting them off from each other.

[Phone ringing]

Bardawil: Hello?

Rosin: Marwan, this is Hanna.

Bardawil: Hi, Hanna.

Rosin: Oy yoy yoy, I couldn’t—we couldn’t reach you for—we couldn’t reach you. Is everyone safe?

Bardawil: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Rosin: What, what was it—what happened in the last few days?

Bardawil: They disconnect all the internet and communication, from Friday noon ’til Sunday morning.

Rosin: Marwan explains to me how they felt that weekend, and the word he used was blind. No calls in or out. No reaching the Red Cross or the UN. No reaching family. No reaching the guy who brings the water tank to their apartment. No way of knowing what was going on outside their walls. But now, with the phones back on, Marwan had work to do. He had to take care of a damaged pipeline.

Bardawil: Sorry, can we talk later?

Rosin: Yes, of course. Yes, of course.

Bardawil: Because I have to take care of some of the damage in one of the pipelines.

Rosin: This was on Monday. The Israelis had opened up a second pipe, and a spokesperson with the Israeli Defense Forces said that now, these two open pipes should provide enough water to meet basic humanitarian needs.

But the second pipe was damaged, so Marwan had to find a technician to fix it. We reconnected later in the day.

Bardawil: Yeah, let’s hope that this pipeline will start functioning tomorrow.

Rosin: Is this a big relief or it’s just small?

Bardawil: It will serve a population of around a quarter million.

Rosin: Oh, good. That’s good.

Bardawil: It’s a big one, yes.

Rosin: That’s good.

Rosin: It was a good moment. A quarter million people getting clean water would be a huge relief. But when we spoke the next day, the pipe still wasn’t running.

And the first pipe, that one was down too. Marwan told me it was a technical issue. He said both should be running soon.

But the reality was that for now, at the moment he and I were talking, they were back to where they’d been at the start of the war: zero pipes working.

Bardawil: The people are in need, really in need for each drop of water. People cannot practice their normal hygiene practices. And this surely will impact their health.

Rosin: Right. So every drop of water is important.

Bardawil: Sure, yes. (Coughs.)

Rosin: Are you okay? Did you get sick?

Bardawil: Yeah, I got the flu.

Rosin: Oh, no.

Bardawil: Yeah.

Rosin: (Sighs.) I’m very sorry.Bardawil: It’s not the time for it, but you know, the environment is full of dust.

Rosin: Every time I called him, he seemed more exhausted, which makes complete sense. Gazans are depending on him. His neighbors are depending on him. His family is depending on him. He’s physically tired, but also just thoroughly exhausted.

Bardawil: We deserve a life which is suitable for a human being. We deserve a better life.

When the peace process was started back in 1993, the majority of the Palestinians dreamed that maybe this is the time that we will have the same opportunities as others.

And we dreamed that maybe this is the chance, but things went beyond the control of the normal people. We are the normal people. We are not the players of this game.

Rosin: “We are not the players of this game.” That evening, we talked some more. He told me about times he traveled to Europe to learn more about water management. And he told me he wasn’t sure his kids would want to raise their families in Gaza.

After about 20 minutes, I wanted to let Marwan get some rest. He told me he was the only one still awake in his house. While we were talking, his wife, kids, and grandkids had all gone to sleep.

Rosin: Everybody’s sleeping? Just you’re not sleeping?

Bardawil: Yeah, because sleeping nowadays, it’s like, when you have the opportunity to sleep, you jump to the bed. Because you don’t know when things will deteriorate around you—voices and the bombing could be close. Even if you feel that you are far away from anything, the atmosphere, the environment around you is scary.

Rosin: So you just can’t hear anything; it’s very quiet, so everyone just goes to bed?

Bardawil: Yes, you caught me in the last moment before I went to sleep.

Rosin: Okay, Marwan, you know what? Go to sleep. (Laughs.) I think maybe you should go to sleep, because you’re also sick. Um, so why don’t you go to sleep, and sleep well while it is quiet. And if we need to, I will call you again tomorrow.

Bardawil: Yeah, you are welcome.

Rosin: Okay, thank you so much, and I hope you rest.

Bardawil: You are welcome. You are welcome.

Rosin: Okay. Okay, bye.

Bardawil: You are welcome. Bye-bye.

[Music]

Rosin: At the time of this recording—Wednesday, November 1—we couldn’t get the latest water update from Marwan. Gaza was under another communications blackout.

This episode was produced by Kevin Townsend, edited by Claudine Ebeid, engineered by Rob Smeirciak, and fact-checked by Sam Fentress. Claudine is the executive producer of Atlantic Audio. Andrea Valdez is our managing editor.

I’m Hanna Rosin. We will be back next week.