The Most Consequential Act of Sabotage in Modern Times

The destruction of the Nord Stream pipeline curtailed Europe’s reliance on Russian gas. But who was responsible?

This article was featured in the One Story to Read Today newsletter. Sign up for it here.

I. A Small Earthquake

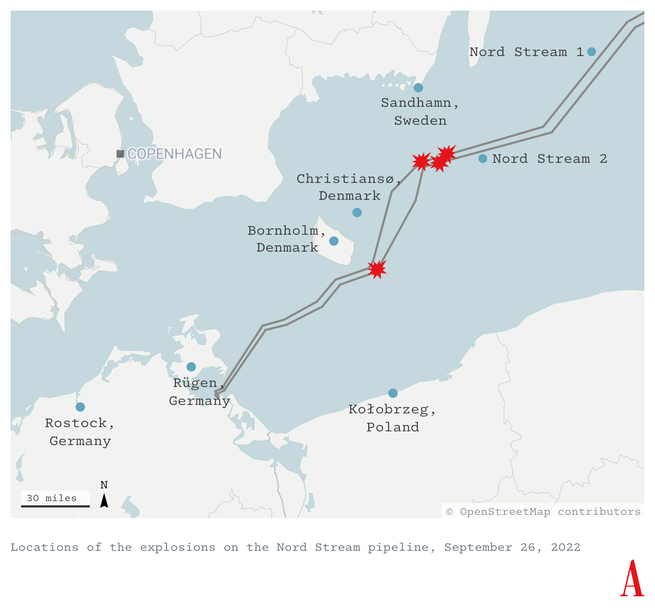

At 2:03 a.m. on Monday, September 26, 2022, at the bottom of the Baltic Sea, an explosion tore open one of the four massive underwater conduits that make up the Nord Stream pipeline. The pipe, made of thick, concrete-encased steel, lay at a depth of 260 feet. It was filled with highly compressed methane gas.

Pressure readings would show a sudden plunge as compressed gas screamed through the breach at the speed of sound, tearing the pipe apart and carving deep craters on the seafloor. Gas escaped with enough force to propel a rocket into space. It shot up and up, creating a towering geyser above the surface of the water.

There was no one in the vicinity—the middle of the sea in the middle of the night—to see or hear any of this, but the event registered with the force of a small earthquake on seismometers 15 miles away, on the Danish island of Bornholm. Because the explosion had occurred in Danish waters, Denmark dispatched an airplane to investigate. By then, the geyser had settled into a wide, turbulent simmer on the surface. The Danish Maritime Authority ordered ships to steer clear. Airspace was restricted. A pipeline executive in Switzerland, where Nord Stream is based, urgently exchanged information with officials in Denmark and other countries.

Nord Stream had been built in two phases, NS-1 and NS-2, each consisting of two pipes labeled A and B. The pipes, with an internal diameter of about four feet, reached across 760 miles of seafloor from Russia to Germany. Given the pressure readings and the location of the surface turbulence, the ruptured pipe appeared to be NS-2A.

No one knew yet what had happened. There were innocent explanations—none of them likely, but some certainly plausible. The pipeline may have sprung a leak on its own. Or some accident or natural event may have disturbed the sea bottom. The area around Bornholm is prone to small earthquakes, and the Baltic Sea is littered with explosive debris. It was heavily mined during the Second World War and, at war’s end, became a dumping ground for unused munitions. Efforts to clear the seabed continue, and live ordnance is often detonated in place. Fishing vessels trawl the bottom—sometimes leaving scratches on the surface of pipelines—and occasionally set off an old mine or bomb. On a typical day, Swedish seismologists detect dozens of underwater explosions, some accidental, some deliberate. But the Nord Stream pipes were built to withstand such blasts and had been placed in lanes painstakingly cleared of hazards.

Any thought that the break was an accident vanished at sunset, when new explosions on the pipeline were recorded, 17 hours after the first one. It would eventually be determined that there were three of them, and that they occurred about 50 miles northeast of the initial blast and about 50 miles east of the Swedish coast, near the edge of that country’s maritime economic zone with Denmark. The blasts scattered several 26-ton, 40-foot-long segments of pipeline on the seafloor. At this northern site, there were witnesses. An officer aboard a German cargo ship, the Cellus, saw what seemed to be the surface eruption from an underwater explosion; the captain of the ship, looking for himself, later reported “something that appeared like a dense cloud” above the water. A photo taken several minutes after the first sighting captured a bubbling swell of gas-infused seawater, which calculations from the digital image showed to be nearly 200 feet high and more than 1,000 feet wide.

Now, with two blast sites—a southern site, with a single explosion, and a northern site, with three explosions—it was clear that someone had attacked Nord Stream, the biggest natural-gas delivery system from Russia to Western Europe ever built. NS-1 had opened in 2011 and had been delivering cheap Russian gas to Germany for a decade. Construction on NS-2 was started in 2016 and finished in 2021, and was filled with gas to prepare for launch. For reasons that were not apparent, only three of the four Nord Stream pipes had been hit—a fact that would intrigue investigators. If the goal was to disable Nord Stream, why leave one of the pipes intact? Had a preset bomb failed to explode?

Together, the four Nord Stream pipes had been capable of supplying as much as 65 percent of the European Union’s total gas imports. Not everyone had been happy about this. The United States feared that Europe’s reliance on Nord Stream would give Russian President Vladimir Putin too much economic leverage. The pipeline promised cheap energy for Europe and decades of revenue for Gazprom, the state-owned Russian energy giant with strong ties to Putin. The pipeline would also reduce the value of older gas pipelines in Eastern Europe, notably the system owned and operated by Ukraine.

After Russia’s invasion and occupation of Crimea, in 2014, resistance to Nord Stream stiffened. The United States imposed a mounting series of sanctions against Russia’s energy sector. So did European nations. Last year, despite the anticipated financial strain on Europe, President Joe Biden was able to gain a promise of European support as Russian armies massed to invade Ukraine once again. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz agreed to prevent NS-2 from opening if Putin attacked. In February 2022, at a White House press conference with Scholz, Biden warned, “If Russia invades … there will no longer be a Nord Stream 2. We will bring an end to it … I promise you we will be able to do it.” This warning was reiterated in equally plain terms by top members of his administration.

When the war came, NS-2’s pipes stayed shut, and severe multinational economic sanctions were imposed on Russia. Putin responded by gradually choking off the flow of gas from the older NS-1 (“maintenance reasons” were cited), which drove up energy prices in Europe—precisely the scenario foreseen. According to some estimates, energy prices in the EU quadrupled. In the summer of 2022, Putin shut down NS-1 completely. By September, the war seemed deadlocked. As winter approached, pressure to deal with energy issues began to grow in Europe.

The four underwater explosions on September 26 made any debate over Nord Stream moot. The attack on the pipeline—without loss of life, as far as we know—was one of the most dramatic and consequential acts of sabotage in modern times. It was also an unprecedented attack on a major element of global infrastructure—the network of cables, pipes, and satellites that underpin commerce and communication. Because it serves everyone, global infrastructure had enjoyed tacit immunity in regional conflicts—not total but nearly so. Here was a bold act of war in the waters between two peaceful nations (although Sweden and Denmark both support Ukraine). It effectively destroyed a project that had required decades of strenuous labor and political muscle and had cost roughly $20 billion—half of that money coming from Gazprom, the other half from European energy companies. The attack was a financial blow to Russia and upended the EU’s energy planning and policy.

There may have been more daring capers, but one recently retired U.S. military commander, a man who has held senior appointments and is knowledgeable about the Baltic region, couldn’t help but acknowledge what he called the “coolness factor” of the Nord Stream attack. Cool, because whoever did it managed to achieve total surprise and leave few traces behind. Indeed, more than a year later, nobody knows for certain who was responsible, although accumulating evidence has begun to point in a specific direction. Officials from Sweden, Denmark, and Germany would answer none of my questions. Nor would officials at the White House, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, or the Pentagon comment on the record, beyond denouncing the act as sabotage. Sweden, Denmark, and Germany have initiated criminal investigations, but very little has emerged about the conduct of any of these probes. That has surprised some journalists, who are used to a leakier status quo. None of the relevant investigating authorities has announced a clear finish line, although Swedish officials have expressed the hope that a decision on whether to bring charges could be made by the end of the year.

“Nobody really wants to clear it up,” suggested the Swedish diplomat Hans Blix, who at 95 is one of his country’s most honored citizens. A former minister of foreign affairs, he is best remembered in the U.S. for contradicting President George W. Bush’s claim that Saddam Hussein had stockpiled weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. (Blix was in charge of the United Nations’ monitoring effort there, and his skepticism proved well-founded.) I met him in his spacious apartment in central Stockholm, moving with the help of a walker—“this condition is not just old age,” he explained, but a consequence of tick-borne encephalitis. His mind was as fresh and independent as ever. We considered various theories about the Nord Stream sabotage—the Russians did it; the Americans did it; the Ukrainians did it. “I end up not convinced of any conclusion … yet,” Blix told me, echoing what he had said in an earlier email. He smiled and added, “And is not that the wish of all parties?”

II. Gas as a Weapon

Nord Stream was an astonishing engineering feat, even if the details of its creation attracted little of the world’s notice. The oceans and seas are threaded with cables and pipelines. Few people give much thought to how they got there. Nord Stream took a quarter of a century to build. Initial planning studies for a new gas pipeline under the Baltic Sea were launched in 1997, when Gazprom joined forces with a Finnish oil company, Neste. This was the era when Boris Yeltsin, then the Russian president, was making boozy trips abroad to sell the capitalist West on the boundless opportunity of investment in his country.

Engineers determined that a direct pipeline from Vyborg, northwest of St. Petersburg, to Lubmin, on the north coast of Germany, would be commercially and technically feasible. The project had broad support: Many European companies wanted in. Compared with coal and oil, natural gas was relatively cheap, safe, and clean. Nord Stream seemed to herald a new era. Russia was at long last joining the peaceful, cooperative commonwealth of Western Europe. Construction of the pipeline began in 2010.

The underwater environment was challenging. The bottom of the Baltic Sea is rocky and irregular. Pipe had to be laid across hundreds of miles of subsea terrain without disturbing the marine ecosystem, disrupting the fishing industry, or destroying historically valuable wrecks. The Baltic’s low salt content is hostile to wood-boring shipworms, so even ancient sunken vessels tend to be well preserved, and the seabed is a prized hunting ground for marine archaeologists.

One man who has specialized in underwater work in the Baltic is Ola Oskarsson, a retired Swedish naval demolition diver. Oskarsson lives on his own small island, Keholmen, south of Gothenburg, on Sweden’s west coast. The island, a rock outcrop, once held a ship-repair business and still has on its west side an idle crane and a slip for hauling vessels out of the water. Oskarsson’s big house is paneled with rough-hewn pine and stained with tar, and has wide windows that look out across the sea.

Oskarsson has a lifetime of experience on and below the water, first for the Swedish navy, then running a business specializing in underwater research, surveying, and exploration. He is weathered and fit in his 70s, tall and blue-eyed, with a trim gray mustache and bright-white chin whiskers. He is an animated storyteller. Once, not content to simply describe for me the breach of the Nord Stream pipes, he jumped onto his front deck to rig an experiment with a pressurized hose, showing how an underwater pipe might have reacted to a sudden rupture.

At the time Nord Stream was being conceived, Oskarsson’s company, MMT (Marin Mät Teknik), was still relatively small. It had one ship and 50 employees. Word of a big Baltic pipeline project spelled opportunity, so he and his business partner traveled to Switzerland, where the NS-1 project had set up shop, to pitch themselves for the underwater surveying and mapping. As Oskarsson recounted, they were informed that all such work had already been taken care of by a Russian company. They were on their way out the door when his partner asked, out of curiosity, “Have you found any mines?”

“No,” came the answer. “Why do you ask?”

Astonished, the Swedes explained what they knew about the dangers lurking on the Baltic seafloor—and MMT was hired. The company expanded to seven ships and 350 employees. In the course of their work, the MMT survey teams found 400 unexploded mines.

They and other teams on the project found plenty else, too: sunken World War II submarines, and a wreck that may have been eight centuries old. Oskarsson was enthusiastic about his work. As he saw it, MMT was not only making money but helping to narrow the Cold War divide and preserve the Baltic Sea’s historic and environmental integrity.

Laying the pipeline has been likened to building a railroad underwater. Swaths of seafloor had to be swept of hazards; occasionally holes and depressions had to be bridged. The pipes themselves were fabricated on shore in segments and shipped out to “lay barges”—flat vessels longer than a football field. Studded with cranes and crawling with hundreds of workers, the barges served as platforms on which prefab segments were welded together, end-to-end. The seams were coated with expandable polyurethane foam to minimize potential snags. When that was done, the ever-lengthening pipes were eased off the barge at a carefully calibrated angle toward the water. The steel pipe, encased in concrete, had to be flexible enough to bend from the barge to the water, yet strong enough to contain highly pressurized gas and to withstand any shocks from outside. As the barges slowly advanced, the pipelines slipped into the sea until they settled on the bottom.

A fleet of ships and helicopters supported the barges, delivering crews, equipment, tools, and food. Work continued day and night. The first of the two NS-1 pipelines began delivering natural gas from Russia to Europe in 2011, the second in 2012.

Meanwhile, preliminary work had begun on a parallel pair of pipelines, NS-2. But the political climate was changing. Putin, reelected to a third term, was aggressively consolidating his autocratic rule and installing himself as leader for life. He was also throwing Russia’s military weight around. As prime minister, in 2008, he had overseen the invasion of Georgia, and when he retook the presidency, he occupied Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula. Democracy in Russia vanished. Opponents and critics of Putin’s regime were harassed, jailed, and sometimes killed. Russia’s cheap natural gas was no longer seen as a friendly bond but as a weapon—a way for Putin to pressure the EU. Some investors and governments may once have resisted (and resented) American arguments against the pipeline, but after the invasion they curtailed their involvement.

Oskarsson cut his own company loose before the NS-2 was even finished. He had met Putin once, at a ceremonial event for NS-1 around the time of its opening. Leaders from the surrounding nations had all been gathered. As Oskarsson recalls, he was standing with Angela Merkel, Germany’s chancellor at the time, when Putin arrived with an entourage of seven bodyguards. Putin is short, and seemed to have deliberately picked bodyguards who were even shorter. Merkel commented, “Snow White and the seven dwarfs.” The breaking point came years later, when, according to Oskarsson, his company was subject to an extortion demand in return for a contract on a different pipeline project. Oskarsson told the Russians, “We don’t pay bribes.”

By September 2022, Nord Stream, this hopeful project, the proud achievement of engineers who had spent much of their careers on it, sat primed and poised on the sea bottom, fully pressurized and waiting, an international rem non voluerunt—a thing not wanted.

III. Blaming the Bear

In the absence of facts, speculation and misinformation rule. At the time of the Nord Stream attacks, many people assumed that blowing up pipelines at the bottom of the sea would require the prowess of a big, modern navy with sleek submersibles, skilled divers, and very large bombs. So the two prime suspects immediately became Russia and the United States. Both countries have denied any involvement, but, under the circumstances, wouldn’t they?

Working 260 feet underwater can be challenging. Visibility is zero (divers work with lights) and the water pressure extreme (about 115 pounds per square inch). Nitrogen under such pressure becomes narcotic, so the air breathed by divers is mixed with helium to lower the exposure. Ascending to the surface without the aid of a recompression chamber or a diving bell requires divers to pause multiple times on the way up to allow their bodies to adapt. Both the Russian and American navies have the personnel and the specialized technology to conduct sophisticated deep-sea operations as needed. An autonomous submersible might even obviate the need for much diving. Among the other nations with a big navy—the United Kingdom, Iran, India, China—none had much of a motive to attack Nord Stream.

Russia, in the words of the Foreign Policy columnist Emma Ashford, writing in June 2023, “seemed to be the most obvious candidate.” Putin, according to this logic, had blown up his own pipeline primarily to punish Europe for its solidarity with Ukraine. Further—a Putinesque twist—if suspicion could be quietly cast on Kyiv, then support for Ukraine might itself be undermined.

This explanation was immediately popular in Sweden. There was no direct evidence for it, and the Kremlin called such suspicions “stupid,” but journalists and amateur sleuths found suggestive patterns in Russian ship movements in the Baltic during the days and months prior to the blasts. Specifically, they identified military vessels that had lingered near the blast sites during the summer. That said, Russian naval traffic is common in the area.

“Of course, in Sweden, the automatic reaction from the press or the media was that the Russians did it themselves,” Mattias Göransson told me. Göransson is the founder and editor of a popular literary and journalistic Swedish magazine called Filter. He is also the author of a book titled The Bear Is Coming!, which examines (and pokes fun at) his country’s preoccupation with its unfriendly neighbor to the east. “It’s very counterintuitive,” he said of the finger-pointing at Moscow, “but it’s a foolproof argument”: If you can’t explain some Russian act or behavior rationally, then you can always say, “‘But you know the Russians. You never know how they think’ … It’s very funny in a way.”

Funny or not, the theory was developed in a ponderous three-part Scandinavian public-television documentary, Putin’s Shadow War, which aired last April and May. It didn’t present any solid new evidence, just speculation and a menacing litany of aggressive acts by Russia. But the contention gained broad traction, and not just in Scandinavia.

“Nobody benefits from this except the Russians,” Ben Hodges, a retired lieutenant general who commanded the U.S. Army in Europe until 2017, told me. “Not only does it serve as a potential wedge”—between Ukraine and its Western supporters—“but it also sends a message, even if it doesn’t have Kremlin fingerprints on it yet, to the Scandinavian countries that their energy infrastructure is very vulnerable, that it can be destroyed.”

Many EU nations had stood with Ukraine when Russia invaded, and Kyiv has relied heavily on their economic and military support. In the spring of 2022, Germany was weighing whether to supply state-of-the-art Leopard combat tanks to Ukraine. Feeling newly threatened by Russia, Finland joined NATO and Sweden ditched a more than 200-year tradition of neutrality to apply for membership. So perhaps Putin was sending a message: There was a price to pay for poking the bear.

But the logic is strained. Russia was hurt more by the sabotage than any other nation. It had spent billions to build the pipeline and theoretically stood to profit from it for years to come. Why would Putin destroy it when he could simply keep it shut? The Ukraine war will not last forever. That said, the retired U.S. military commander and senior appointee observed, “A lot of things they’re doing just don’t pass the sanity check.”

A former CIA officer, who spent decades at the highest levels of intelligence-gathering, characterized the Russia theory to me as “too complicated,” especially if it involved trying to pin the sabotage on Ukraine. He went on: “If you’re in Moscow and you’re going through all of this … you’re going to know that you’re going to be blamed, right? Even if you can blame the Ukrainians, you know you’re going to be blamed. So, it doesn’t make any sense.”

Emma Ashford, in her Foreign Policy column, ended up dismissing the possible Russian motives for an attack on the pipeline as “weak.” Although some observers still hold to the theory, Russia is an unlikely suspect.

IV. Next on the List

One can almost see the movie—the dark suits and cornpone accents in a shadowy glass room in Washington. Like Russia, the U.S. has the military know-how to mount sophisticated undersea operations, and it had a motivation that had been articulated by the president himself. America is also everyone’s favorite hidden hand when it comes to international skulduggery.

The suspicion that the U.S. was involved in the sabotage was given a big boost in some minds by the celebrated journalist Seymour Hersh. In February, Hersh published on his Substack a confident and detailed article titled “How America Took Out the Nord Stream Pipeline.” He presented the account simply as fact. Hersh’s history of blockbuster revelations about episodes of American wrongdoing—among them, the My Lai massacre in Vietnam and the torture of prisoners in Iraq—gave his story weight. But some of Hersh’s recent work has raised questions. Relying heavily on one unnamed source, his 2015 article about the killing of Osama bin Laden, published by The London Review of Books, flatly contradicted every other account of the mission, including my own and those of mission participants.

Hersh’s account of the Nord Stream sabotage appeared also to have relied heavily on a single unnamed source, and a remarkable one at that. The source provided accounts of top-secret meetings at the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, secret meetings of CIA and NSA working groups, and planning sessions in Norway, as well as specific details of the mission itself, including tools and methods.

According to Hersh, the decision to bomb the pipeline was made by Biden in early 2022. After months of indecision, it was carried out by American divers schooled at the Naval Diving and Salvage Training Center in Panama City, Florida, who had “repeatedly practiced” placing explosives on pipelines. The mission was staged in Norway, where that country’s naval experts chose the precise spots to place bombs on each of the four pipes. A Norwegian Alta-class mine hunter was used as a platform for the dives, which were made during a regular NATO exercise called BALTOPS 22, which employed “the latest underwater technology.” There would have been plenty of warships in the Baltic Sea to provide cover. A research exercise was invented as a facade. The bombs were planted in June and ultimately triggered by a signal from a sonar buoy dropped on September 26 by a Norwegian P-8 surveillance plane on a routine flight. In an interview with Berliner Zeitung, Hersh elaborated, saying that eight bombs had been planted, which made sense: two bombs on each pipe, for redundancy.

It was a neat, authoritative play-by-play. For anyone inclined to suspect the U.S., it offered a plausible scenario of what America might have done. No conflicting information was presented. But it broke down in the details. Ship movements near the blast sites during the naval exercise didn’t add up, and no Alta-class mine hunter had taken part. Independent flight-tracking data showed no record of a Norwegian P-8 flight in the area on September 26. Hersh maintained that eight explosives had been placed on the pipes, but there appear to have been only four explosions. He also reported that NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg, himself Norwegian, had been cooperating with U.S. intelligence since the Vietnam War, when the 64-year-old statesman was still a child. Hersh dutifully reported the White House response: “This is false and complete fiction.” He received a similar response from the CIA.

The USS Kearsarge, an amphibious assault ship, during a NATO exercise in the Baltic called BALTOPS 22 (Jonathan Nackstrand / AFP / Getty).

The Hersh article has been analyzed and criticized by a number of knowledgeable investigators. My own military and intelligence sources were unanimous in discounting the idea of American responsibility. These are people who have hands-on experience with covert U.S. military missions over many decades. In previous interactions, they have responded to sensitive questions they didn’t want to answer with “No comment.” In those instances where they have agreed to share information with me, it has always been correct.

“I’m at a loss to know who actually did it, other than the fact that we didn’t do it,” the retired U.S. military commander told me.

The former high-ranking CIA officer, a man who can draw on long experience in the White House Situation Room, from which covert operations are often launched, was unequivocal: “Without a doubt, the United States did not do this. There is no way the Biden administration would. If it was the Trump administration, it might be a different story. But there’s no way that Biden would ever sign off on doing something like that.”

The logic was clear. One of the triumphs of Biden’s presidency has been rebuilding NATO and repairing ties with Europe that were strained during Trump’s tenure. And one of Biden’s proudest achievements is the international coalition that keeps Ukraine supplied with war-fighting matériel. The bonds of that partnership are not sturdy. They have been sustained by aggressive persuasion. Would Biden put all of that in jeopardy? No matter how carefully a covert mission like an attack on Nord Stream is executed, history shows that the truth will come out, usually sooner rather than later. If the U.S. were discovered to have attacked a major piece of its allies’ energy infrastructure, the information might shatter his coalition. And why risk it? The pipelines were already idle. There is also, despite the Hollywood cliché, an inbred reluctance in the U.S. military and intelligence community to conduct missions that might trigger strong political blowback.

Russia had blamed the United States for the blasts immediately, and when Hersh’s story came along, it was embraced by Putin and his Russian media. It was also embraced by right-wing American pundits with their own political agendas. Tucker Carlson, still a Fox News host at the time, emphatically pronounced Hersh correct: “So many details in here. It is not possible that it’s not true. It is true!”

When the story appeared, it represented the only detailed narrative explanation of exactly what had happened, and for that reason alone many people were swayed by it. And Hersh has expressed no doubts. But in light of the broader context, America, like Russia, seems to be an unlikely suspect.

Neither Big Navy theory is convincing: For different reasons, both Russia and the U.S. would have little to gain and much to lose. Meanwhile, facts have emerged that offer a very different perspective.

V. The Andromeda Connection

Ola Oskarsson, the diver and surveyor, viewed initial speculation about the bombing with a more practiced eye than most. In addition to his military service, when he handled explosives underwater, and his Nord Stream service, when he helped locate 400 mines in the pipeline’s path, he has supervised commercial underwater operations in the Black Sea, the North Sea, the South China Sea, the Indian Ocean, and Lake Victoria. He has surveyed almost all of the undersea power and telecommunications cables in the Baltic at one time or another. He helped find and remove old listening devices from the ex-Soviet submarine base near Paldiski, Estonia, after the U.S.S.R.’s collapse, in 1991. Over the years, Oskarsson has maintained close friendships with military and commercial divers, and he knows that world as well as anyone.

He also maintains friendships with journalists, who prize his expertise. And he had been telling them that certain widespread assumptions about the Nord Stream bombing were mistaken. The explosives did not have to be all that large, he maintained, and breaching a gas pipeline would not require the most advanced technology on the market. In other words, you wouldn’t need Big Navy resources.

Oskarsson has no direct knowledge of the Nord Stream attack, but he does have suspicions. “I think I know pretty well how it was exploded,” he told me. He believes it was done by “a little sea group, two to six people in a rubber boat”—a Zodiac, say, launched from a fishing vessel or private yacht as a base of operations. His scenario starts with a standard vessel large enough to take half a dozen people on a cruise. Most Swedes live on or close to the water, and there are hundreds of thousands of privately owned boats in the country. Its 2,000-mile coastline is notched and dotted with a seemingly endless series of inlets and small islands—indeed, the capital city, Stockholm, is itself a cluster of 14 islands. You can smell water from just about everywhere except the pine forests of the interior. Large vessels are closely monitored, but tracking the multitude of small fishing boats and yachts is impossible. A vessel being used as a platform for the attack need not even have anchored over the submerged pipes, whose exact position is well known; it could have stayed some distance away and launched a Zodiac at night. A line dragged along the seafloor would snag a pipe and provide a dive rope. Descending, divers wearing rebreathing apparatus could stay submerged for hours. Military-grade explosives, small enough to be carried in a backpack, could then be affixed to the concrete shell of the pipes. The operation would likely have required as many as four dives, one for each pipe, depending on the number of divers involved. And it would have been strenuous. But if the crew rested on the larger vessel during the day, it would have been doable. This approach also had the virtue of being simple, inexpensive, and completely inconspicuous.

And evidence exists to support this scenario. Although officials in Sweden, Germany, and Denmark have said little about their ongoing investigations, journalists both in and outside the region have pieced together a story similar to Oskarsson’s basic idea from government sources and determined legwork.

On March 7, The New York Times reported that American intelligence officials had come to suspect that divers from a pro-Ukrainian group had sabotaged Nord Stream. That report prompted a consortium of journalists from Germany, Sweden, and Denmark—brought together by Georg Heil, a journalist who works within Germany’s public-broadcasting conglomerate—to rush ahead with the first in what would be a series of reports in German news outlets and on regional TV stations. They had been accumulating information for months and had hoped to flesh out their findings in greater detail before publishing, but the Times article forced their hand.

They offered a lot more than the Times. Their reporting linked the bombing to a small crew of divers working off a yacht—a private vessel that had made a stop at a marina in Wieck am Darss, a German port on the southern edge of the Baltic. The boat carried a group of six: a captain, two divers, two diving assistants, and a doctor. Passports presented by the crew proved to be fake. When the boat was returned, it was found to contain traces of an explosive. All this information had come from sources cultivated within the German police. A subsequent article by the magazine Der Spiegel named the boat: Andromeda.

The consortium of journalists had in fact known the name since January—and not only from German sources. The team’s Danish reporter, Louise Dalsgaard, was able to confirm that authorities in Denmark were also interested in Andromeda. Fredrik Laurin, a prominent and respected Swedish journalist whose work is featured on a 60 Minutes–like program on Swedish public television called Mission: Investigate, was determined to find the boat—not an easy task when dealing with multiple jurisdictions and proprietary record-keeping.

When I met with him in Gothenburg, Laurin told me that he had contacted a young woman, the daughter of an old sailing friend, whom he knew had worked as a harbormaster on Germany’s north coast. He figured she knew more than any journalist did about boats, ports, and rentals on that side of the Baltic. She was happy to be consulted; the project sounded exciting—perhaps a little too exciting, because she didn’t (and still doesn’t) want her name connected with it.

When I spoke with her by phone, she seemed pleased with her contribution. She and Laurin had made the assumption that Andromeda was probably a yacht—possibly a Bavaria, a very popular sailing vessel on the Baltic. A motorized vessel big enough for a six-person crew would be more likely to attract attention, as would a large purchase of diesel fuel, which it would need to travel across more than 100 miles of sea from the German port to the blast locations. A sailboat would not need that much fuel and, on the water, “would look like a charter tourist who is just lost, or swimming,” she said.

Because the harbor depth at Wieck am Darss was too shallow for a sailboat with a Bavaria’s draft—the consortium journalists would prove to have been mistaken about the location, and later published a correction—the young woman guessed that the Andromeda was likely chartered elsewhere. She started calling companies to ask if they had a vessel by that name. She was having fun. She had to have a reason for the ask, and worried that the truth might spook the people she called. So she played stupid. She knew that the boating communities of north Germany were still almost exclusively male, and decided that pretending ignorance would suit their expectations.

A typical conversation went like this:

“I want to rent a boat this year, and my friends, they rented a boat called Andromeda last year,” she would begin, explaining that her friends had been “so happy with it.” Then she said she didn’t know any details about the boat, even whether it was a motorboat or a sailboat.

“Well, a sailing boat usually has a mast on it,” one of the charter officials told her.

She quickly found what she was looking for. A 50-foot Bavaria called Andromeda had been rented from Mola Yachting, on Rügen, a German island north of Wieck am Darss. And it fit the bill: It had a galley and could sleep up to 10. There was no telling if the authorities had already learned all this, but Laurin spread the word.

In May, Süddeutsche Zeitung, the German newspaper, published “The Fog Is Lifting,” a detailed account of Andromeda’s possible role. Subsequent stories chronicled its doings during September 2022. Many of the stories carry the name Holger Stark (among others), one of the most consequential journalists investigating the Nord Stream attack. According to these reports, the request to Mola Yachting for the Andromeda charter had come from a Google account that appeared to be American but that had actually originated in Ukraine. The yacht had been sighted at ports around the Baltic on a voyage that lasted a little over two weeks. A witness at Rügen remembered five men and a woman who stood out among the usual mix of families and couples renting a yacht for a pleasure cruise. They were seen loading a lot of equipment onto the boat, which a harbor webcam had captured moving out to sea on September 7.

Andromeda was again noticed during a stop at Bornholm, the Danish island near the southern explosion site, and near Christiansø, a tiny island closer to the northern site. Then, two weeks before the blasts, the yacht reportedly sheltered during heavy weather in Sandhamn, a small harbor on the Swedish coast, about 40 miles from the northern site. A German skipper had a slight run-in with its crew, a dispute over boating etiquette, and described two of the men as middle-aged but fit, with military haircuts. He spoke to them in English, which he said was translated by one of the crew into a language that to him sounded Eastern European. A second witness in Sandhamn described the boat’s captain as heavyset and unfriendly. The crew bought some diesel fuel, paying cash in euros, and left on September 13 as the weather calmed. Six days later, Andromeda arrived at the Polish city of Kołobrzeg, closer to the southern site, where the first explosion would occur.

Andromeda had been chartered through a travel agency in Warsaw registered to a woman with a Ukrainian address, and Die Zeit, the German weekly newspaper, tracked down a man associated with the company in Kyiv. Identifying him only as “Rustem A.,” the reporters found that he owned a string of companies, some of them real, some of them without an internet presence or a real-world address. He reacted, when contacted, not with surprise, but with anger. He refused to cooperate and insulted and threatened the journalists. Meanwhile, using the passport photos obtained from the boat-rental company, together with facial-recognition software, journalists had tentatively identified one member of the Andromeda crew as a Ukrainian soldier. (The soldier denied any involvement.)

Additional information became public in June, when The Washington Post revealed the existence of a secret report received by the CIA the previous summer, months before the blasts, outlining a Ukrainian plan to sabotage Nord Stream. According to the Post, the Dutch Military Intelligence and Security Service had warned that Ukraine was planning an attack using a small team of divers.

The contents of the Dutch memo were brought to light when Jack Teixeira, a young U.S. airman assigned to the intelligence wing of the Massachusetts Air National Guard, allegedly began showing off his access to classified documents to a members-only server on Discord, a social platform popular with gamers. Teixeira was arrested this past April, and has pleaded not guilty to multiple federal charges. Some of the posted files were subsequently obtained by The Post. The newspaper’s first detailed account of material related to Nord Stream noted that, according to Dutch intelligence, Ukraine’s plan had originally been set for midsummer 2022, but had been delayed. Six Ukrainian operatives with fake passports would travel to Stockholm, where they would rent a boat and a submersible vessel. They would deliver the bombs, blow up the NS-1 pipeline, and depart undetected. (No mention was made of NS-2.) It said the operation was supervised by Ukrainian General Valery Zaluzhny, the country’s top military commander, but that President Volodymyr Zelensky would not be informed. The details in this summary did not agree with every detail in the findings of the journalistic consortium and other reporters, but the resemblance was clear: a crew of six and a boat.

The accumulation of information pointed circumstantially to Ukraine, or at least a group of Ukrainians. Ukraine has denied involvement repeatedly. “I am president, and I give orders accordingly,” Volodymyr Zelensky said in June, in an interview with the German publishing company Axel Springer, following up on the reports about Andromeda. “Nothing of the sort has been done by Ukraine. I would never act that way.”

But Ukraine had a clear motive. The attack delivered a punishing and enduring economic blow to Russia, which daily rains shells and missiles on Ukrainian cities. By mid-2022, Ukraine had fought off Putin’s initial thrust and taken back much of the territory seized in March. It had hit Russian ships on the Black Sea. Soon it would down part of the Chonhar road bridge, the main Russian link to occupied Crimea; its drones and covert units would be striking Russian targets far from the battlefronts. Knocking out Nord Stream also preserved the value of Ukraine’s own gas pipelines, which have continued to deliver Russian gas to Western Europe even as war has raged. Russia has reduced the flow to a third of prewar levels, but the pipelines still earn important revenue for the embattled nation.

Ukraine does not have a large navy, or anything comparable to the advanced undersea technology that Russian and the U.S. can deploy. But it has demonstrated tenacity and ingenuity—certainly enough to charter a yacht with a Zodiac and send skilled divers down 260 feet with small bombs. This is where things stood one year after the blast, with the United States and Russia still considered suspects by many, but with evidence tilting more strongly to Ukraine.

VI. The Mistake

Solving the Nord Stream mystery has been the province not only of journalists but also of amateur investigators (and conspiracy theorists) who have been active online. Most just offer opinion or conjecture. Some tap expertise that journalists don’t possess. The very rare ones combine expertise with detective work—actual reporting—in the real world. Few people have produced more useful information about Nord Stream—including a possible explanation for why one of the pipes remained unharmed—than a man named Erik Andersson, a well-to-do retired engineer in Gothenburg.

His career began at Volvo, which has its headquarters there. Andersson has a precise mathematical mind and an itch for complex problem-solving. He was drawn to the challenge of scheduling—whether of production or personnel—and a software product he helped build was useful enough that outside companies began approaching Volvo for help. Among them were major international airlines, such as Scandinavia’s SAS and Germany’s Lufthansa. Volvo at first allowed Andersson to put his skills to work creating timetables for the ever-moving army of pilots and crews that commercial air fleets require. He was eventually able to spin off a new company, Carmen Systems, dedicated to the airline work. The software Carmen developed has since become widely used. In 2006, a Boeing subsidiary purchased the company for $100 million. Andersson stayed on for a decade, then retired: wealthy but slightly aimless. Ease didn’t suit him. He took on a few engineering projects and became a philanthropist, an investor, and something of a gambler. At heart he remained a nerd, and he still had that problem-solving itch.

Andersson found an outlet for that itch in conspiracy theories. He was drawn into a murky online world that revolves around topics such as Russiagate, the Steele dossier, and the origins of COVID. Politically, he is on the right. He likes Donald Trump, and in 2016, finding the odds attractive, he bet and won big—$300,000—on the results of the 2016 American presidential election. He has intimated online that he thinks the 2020 election was stolen. Andersson also understands, as he told me, that “going on social media and launching your opinions” is “not good for your health.”

He began conducting actual research. Andersson was intrigued by the Nord Stream mystery, and particularly taken with Seymour Hersh’s rendering of events. He could see that most mainstream media were skeptical of Hersh’s account, but he himself was inclined to believe that the U.S. was behind the explosions. With time and money at his disposal, he decided to begin where detectives usually do, by examining the crime scenes, looking to verify Hersh’s story. Last May, he chartered a boat, bought an undersea drone, assembled a crew, cruised out to the blast sites, and performed his own forensic inspection.

I met Andersson in his airy, high-ceilinged apartment in Gothenburg’s historic center. He is now 63, a sturdy man with a ruddy countenance and short, unruly white hair. His dress shirt was untucked and his pants were wrinkled; his manner was fidgety but patient. My questions were generally broader than the intricate, technical issues that preoccupy him, and I had to keep reeling him up from the depths. Before him on a long table Andersson had unfurled large maps of the Baltic, annotated with his own notes, as well as small plastic models of the undersea blast areas showing deep craters and scattered segments of the Nord Stream pipes. The craters were carved, Andersson suspects, by the force of the escaping methane.

Andersson’s reports on Substack are clearly written and convincing, and they have earned the respect of knowledgeable journalists. Indeed, I had been led to Andersson by Fredrik Laurin. Much of Andersson’s work is based on input from specialists in a variety of fields, and it is taken seriously by people who have experience with the Baltic pipeline. Andersson’s findings tell a story, one that, contrary to his original intention, is at odds with Hersh’s.

Hersh had maintained in an interview that eight bombs were set on the pipeline, and that only six had gone off. In a follow-up Substack article, he referred only to “the one mine that has not gone off”—presumably meaning a mine placed on the undamaged pipe, NS-2B—and nodded at the idea that it had been retrieved covertly by the U.S. Navy afterward. If Hersh still believed that there had been eight bombs or mines—he did not specify a new total in his follow-up—then that suggested there had been seven explosions.

Investigation or inspection by Andersson and others showed clearly that there had been four explosions and strongly suggested that they had been caused by just four bombs. There were four gas plumes: one large one at the southern site that had erupted early in the morning, plus two large ones and one very small one at the northern site, from the explosions 17 hours later. The timing and location suggested that the small plume came from a pipe that had already been depressurized by the initial blast; in other words, two bombs had been placed on the same pipe. Why would the saboteurs leave one pipe, NS-2B untouched, and put two bombs on NS-2A? The answer, as Andersson came to see it, was that they made a mistake. If he was right, then the smaller blast site would yield the best clues about the number and size of the bombs because, unlike at the other three blast sites, there would have been no subsequent catastrophic outflow of gas.

We don’t know whether official investigators have come to this same conclusion, but Andersson’s underwater drone seemed to confirm its accuracy. The first blast on NS-2A—the early-morning one, at the southern site—had done catastrophic damage; the second blast on NS-2A, at the northern site, had simply poked a neat hole in the pipe. There had been no violent burst of escaping methane, just a relative trickle that made its way steadily up to the surface—the small plume. The neat hole also confirmed that the explosive charge used was relatively modest—compact enough to have been carried in a backpack.

Without consulting the perpetrators, there is no way to know why the northern bombs went off 17 hours after the southern one, and there is no way to know whether bombs were placed at the northern site first or the other way around. But it isn’t hard to imagine why there were two separate blast sites. If performed in the simplest way, by divers off a Zodiac, the work would likely have required a series of descents over several nights, and it could have been interrupted—and the boat forced to move—for any number of reasons: bad weather, say, or fuel or supplies running low. Maybe there was just a need to rest. But this is mere speculation. What does seem clear, from all the evidence, is that the divers made a mistake: They put two bombs on the same pipe.

How did they get confused? If the divers were using magnetic compasses, the readings could have been affected by the steel pipeline itself or by a high-voltage underwater cable that lies only about 1,000 yards from Nord Stream at the northern location. That said, in these circumstances, experienced divers would have preferred a sonic device to a magnetic compass. There are plenty of other reasons why divers might have gotten disoriented. Working at such depths is inherently difficult. But the mistake is noteworthy—a piece of what might be called negative evidence. It points away from a Big Navy operation, conducted off a warship with divers who had repeatedly conducted practice runs planting explosives on pipes. In such a scenario, there would also have been no need for a second site. The bombs could all have been planted in a single dive. Weather and supplies would not have been issues.

Andersson’s findings, along with reports about the meandering Andromeda and its crew of six, told a different story.

VII. A Taboo Is Broken

The idea that world-changing events are guided by secretive actors with meticulous plans can be oddly reassuring. It reduces the troubling randomness of reality. Someone in power orders a thing to be done, and it is done.

In his Nord Stream story, Hersh describes a tidy process: an order from Biden, a collaborative effort with Norway, a warship deployed as a platform, and a team of U.S. Navy divers with the best military technology available. This scenario conforms with ideas of a hidden American guiding hand. But in life, things rarely work so smoothly. The Zodiac version is messier: an order from an unknown source, a rented sailboat, a Polish travel agency linked to a snarly Ukrainian, a somewhat noisy crew of divers who left witnesses all over the Baltic, a mission that needed to be paused and then picked up again, and then, possibly, a crucial mistake. Hersh’s version apparently comes from a single unnamed but very knowledgeable source. The messier version comes from scattered, disconnected, unpredictable sources in different places, most of them on the record, each yielding different bits of the story. The messier version leans toward Ukraine.

The Washington Post and Der Spiegel added weight to a possible Ukraine connection in November, when they coordinated the publication of separate articles that told the same broad story, based on shared reporting. The articles named a central player in the sabotage mission—a Ukrainian colonel, Roman Chervinsky. The authors based their stories on “officials in Ukraine and elsewhere in Europe, as well as other people knowledgeable about the details of the covert operation.” Chervinsky, who denied his involvement in a statement from his lawyer, is a decorated veteran of his country’s special-operations forces who, the reporters said, “is professionally and personally close to key military and security leaders.” He reported to Major General Viktor Hanuschak, who “communicated directly” with Ukraine’s top military commander, General Zaluzhny. The article said that Chervinsky handled “logistics and support” for a six-person team that dove from a rented sailboat to place the explosives. The mission was undertaken, the reporters said, on orders from senior Ukrainian military officers who report to General Zaluzhny. This did not necessarily mean that Zaluzhny himself gave the order. Chervinsky is currently under arrest for allegedly abusing his military authority by conducting an unauthorized mission, different from the Nord Stream one (an allegation that he also denies).

So President Zelensky might be telling the truth when he says he never ordered an attack. The Dutch memo to the CIA noted that he would not be informed. Such a mission might have been undertaken on orders from Zaluzhny alone, even in defiance of a hard no from the president. Given the stated U.S. opposition to the pipeline, it’s not inconceivable that there could have been quiet acquiescence from Washington. Such things can be conveyed by a nod or a wink. It is also possible that the mission skirted Ukraine’s military chain of command entirely. A wealthy patriot—someone like, say, Rustem A., believing that Nord Stream’s destruction might benefit his besieged country—might have contracted with someone like Chervinsky to charter a boat and hire a diving team without asking permission from anyone. Such a person might well have assumed that the penalty for success in his own country would likely be gratitude, if not acclaim.

Until there is some formal resolution, unofficial findings and theories are all we have. But the evidence at the scene of the blasts is well documented. A military-like crew aboard the Andromeda definitely wandered in the vicinity of the explosion sites, behavior that may of course turn out to have an innocent explanation. Then there is the explosive residue found on Andromeda. Hersh, for his part, contends that the Andromeda voyage and the explosive residue are part of a carefully constructed ploy designed to steer investigators away from the truth. If so, given the variety of sources and methods used to reconstruct Andromeda’s voyage, it would be a remarkably intricate confection. If the official investigations do identify Ukrainians as the perpetrators, as I suspect they will, many of those inclined to believe the Russia theory or the America theory will hold to their opinions. People tend to believe what they wish to believe, and theories are bound up with political ends.

That said, there are also ample reasons why many are not eager to assign blame—even if, in the end, investigators will have to come to a conclusion. Officially naming Russia, the U.S., or Ukraine as the saboteur would have sticky political consequences all around. The belief that Russia might have carried out the attack has already helped swell military spending in Scandinavia, spending that some in the region oppose. If Russia is shown to be behind the attack, that opposition could lose traction. Identifying Russia as the perpetrator would also put Germany on the back foot: Germany had seen Russia as a partner, and German companies had invested in Nord Stream. Because Germany is now aligned with the United States and Ukraine in resisting Putin’s invasion, pinning the attack on the U.S. or Ukraine would pose its own difficulties. If Ukraine is responsible, it would make that country appear singularly ungrateful, because European arms and ammunition have kept it in the fight. Blowing up a major piece of energy infrastructure in the middle of the Baltic would feel like a betrayal. At the same time, it would make Russia look weak and ineffectual, unable to defend a marquee infrastructure project on its doorstep. The Biden administration, which has worked strenuously to rebuild its alliance with Europe and to rally its support for Ukraine, would appear coldly calculating and two-faced if it was behind the sabotage.

The gas-receiving compressor station in Lubmin, Germany (Krisztián Bócsi / Bloomberg / Getty)

Whoever is blamed, European outrage will likely be muted. Time passes, and memories are short. The environmental damage was minimal. Estimates vary considerably, but the amount of methane released, thought by some to be one of the largest single emissions ever to have occurred, is a small fraction of annual natural releases of the gas. The loss of Nord Stream inflated energy costs for a time, but today they are below where they were before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Workarounds were quickly found. Western Europe, it turned out, had alternatives to Russia’s natural gas.

“The European Union had prepared in earnest for supply disruptions from Russia since 2009, when a Russian cut-off of gas flows to Ukraine forced Bulgaria, an EU member state, to cut off industrial consumers of gas,” wrote Mitchell Orenstein, a University of Pennsylvania professor of Russian and East European studies, in a 2023 article published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute. “Most of these measures did not attract public attention, because of their highly technical nature.” The energy grids of member countries were linked, so that a production slump in one could be offset by others. A pipeline connector between Greece and Bulgaria was opened to allow natural gas to flow from Azerbaijan through the Trans Adriatic pipeline. New terminals were built in Poland, Lithuania, and Germany to enable liquefied natural gas to be imported from the United States and elsewhere.

The loss of Nord Stream also gave a big push to the EU’s green movement, which seeks to replace fossil fuels with renewable-energy sources. Putin was awarded first place in Politico’s “Class of 2023”—a list of top environmental “power brokers.” Taking note of suspicions that Russia had blown up its own pipeline, Politico observed: “Vladimir Putin has done more than almost any other single human being to speed up the end of the fossil-fuel era.” Politico was poking fun, but it should not be forgotten that, whoever was behind the actual bombings, Putin is ultimately responsible for them. He started the war that made Nord Stream a target.

Repairing Nord Stream will not be as simple as putting the shattered pieces back together. In the days and weeks after the blasts, water gradually pushed into the broken pipes, reducing the outflow of methane until the water pressure from outside equaled the gas pressure inside, and stopped the flow. Repairing the pipes—if the effort is even attempted—would be time-consuming and costly. With the EU’s energy priorities shifting away from fossil fuel, repairs might very well never happen.

A year after the blasts, Hans Blix was less worried about the future of the pipeline than about the precedent set by its destruction. Pipelines and electric cables “wire our continents together,” he said the afternoon we met. He wondered if “it was a warning that those who did it could do it in other situations.” He stepped back for a measure of perspective: When you have wars, he said, the restraints come off—but not all of them. “Belligerents may have some common interests still,” such as the exchange of prisoners or the export of grain, interests that can be defined. “The partial [nuclear]-test-ban agreement: That was also a common interest.” Generally speaking, underwater infrastructure has been seen as a common interest, too; but, he said, “maybe that taboo is broken.”

Whatever the official findings, there is a good chance in the end that no one is ever likely to be brought to account for the attack. This is no small thing. A $20 billion engineering feat, built over decades by thousands of skilled workers—a wonder of the modern world—might well rest forever, inert and flooded, at the bottom of the sea.