The Plight of the Eldest Daughter

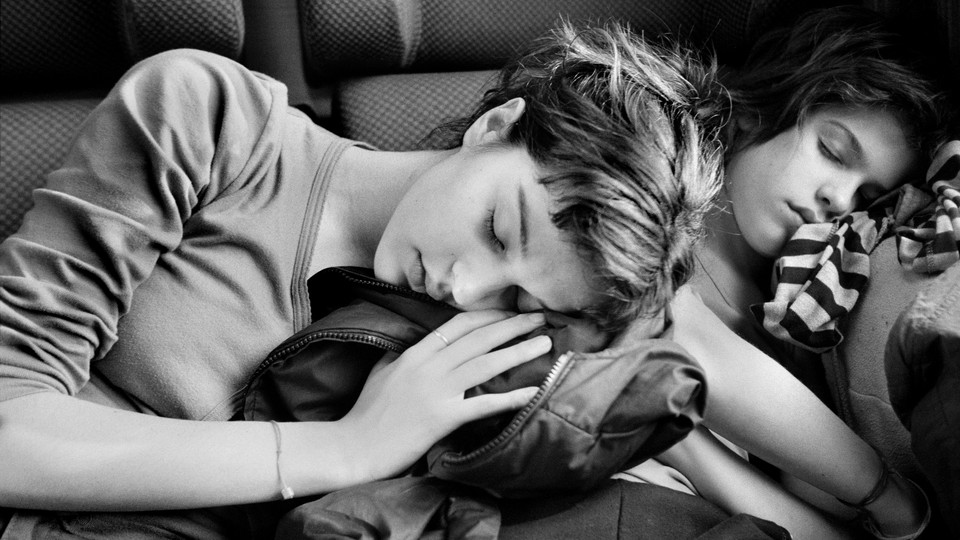

Women are expected to be nurturers. Firstborns are expected to be exemplars. Being both is exhausting.

Listen to this article

Listen to more stories on hark

This article was featured in One Story to Read Today, a newsletter in which our editors recommend a single must-read from The Atlantic, Monday through Friday. Sign up for it here.

Being an eldest daughter means frequently feeling like you’re not doing enough, like you’re struggling to maintain a veneer of control, like the entire household relies on your diligence.

At least, that’s what a contingent of oldest sisters has been saying online. Across social-media platforms, they’ve described the stress of feeling accountable for their family’s happiness, the pressure to succeed, and the impression that they aren’t being cared for in the way they care for others. Some are still teens; others have grown up and left home but still feel over-involved and overextended. As one viral tweet put it, “are u happy or are u the oldest sibling and also a girl”? People have even coined a term for this: “eldest-daughter syndrome.”

That “syndrome” does speak to a real social phenomenon, Yang Hu, a professor of global sociology at Lancaster University, in England, told me. In many cultures, oldest siblings as well as daughters of all ages tend to face high expectations from family members—so people playing both parts are especially likely to take on a large share of household responsibilities, and might deal with more stress as a result. But that caregiving tendency isn’t an inevitable quality of eldest daughters; rather, researchers told me, it tends to be imposed by family members who are part of a society that presumes eldest daughters should act a certain way. And the online outpour of grievances reveals how frustratingly inflexible assumptions about family roles can be.

Research suggests some striking differences in the experiences of first- and secondborns. Susan McHale, a family-studies professor emeritus at Penn State University, told me that parents tend to be “focused on getting it right with the first one,” leading them to fixate on their firstborn’s development growing up—their grades, their health, the friends they choose. With their subsequent children, they might be less anxious and feel less need to micromanage, and that can lead to less tension in the parent-child dynamic. On average, American parents experience less conflict with their secondborn than with their first. McHale has found that when firstborns leave home, their relationship with their family tends to improve—and conflict then commonly increases between parents and their younger children, because the spotlight is on them. Birth order can also create a hierarchy: Older siblings are often asked to serve as babysitters, role models, and advice-givers for their younger siblings.

To be clear, birth order doesn’t influence personality itself—but it can influence how your family sees you, Brent Roberts, a psychology professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, told me. Eldest kids, for example, aren’t necessarily more responsible than their siblings; instead, they tend to be given more responsibilities because they are older. That role can affect how you understand yourself. Corinna Tucker, a professor emerita at the University of New Hampshire who studies sibling relationships, told me that parents frequently compare their children—“‘This is my athlete’; ‘this is my bookworm’; … ‘so-and-so is going to take care of me when I’m old’”—and kids internalize those statements. But your assigned part might not align with your disposition, Roberts said. People can grow frustrated with the traits expected of them—or of their siblings. When Roberts asks his students what qualities they associate with firstborns, students who are themselves firstborns tend to list off positives like “responsible” and “leadership”; those who aren’t firstborns, he told me, call out “bossy” and “overcontrolling.”

Gender introduces its own influence on family dynamics. Women are usually the “kin keepers,” meaning they perform the often invisible labor of “making sure everybody is happy, conflicts are resolved, and everybody feels paid attention to,” McHale told me. On top of that emotional aid, her research shows, young daughters spend more time, on average, than sons doing chores; the jobs commonly given to boys, such as shoveling snow and mowing the lawn, are irregular and not as urgent.

Daughtering is the term that Allison Alford, a Baylor University communication professor who researches adult daughters, uses to describe the family work that girls and women tend to take on. That can look like picking up prescriptions, planning a retirement party, or setting aside money for a parent’s future; it can also involve subtler actions, like holding one’s tongue to avoid an argument or listening to a parent's worries. Daughtering can be satisfying, even joyful. But it can also mean caring for siblings and sometimes for parents in a way that goes above and beyond what children, especially young ones, should need to do, Alford told me.

Research on eldest daughters specifically is limited, but experts told me that considering the pressures foisted on older siblings and on girls and women, occupying both roles isn’t likely to be easy. Tucker put it this way: Women are expected to be nurturers. Firstborns are expected to be exemplars. Trying to be everything for everyone is likely to lead to guilt when some obligations are inevitably unfulfilled.

Of course, these conclusions don’t apply to all families. But so it is with eldest daughters: Although not all of them are naturally conscientious or eager to kin-keep, our cultural understanding of family roles ends up shaping the expectations many feel the need to rise to. The people describing “eldest-daughter syndrome” are probably all deeply different, but talking about what they share might make their burdens feel a little lighter. And the best-case scenario, Alford told me, is that families can start renegotiating what daughtering looks like—which should also take into account what eldest daughters want for themselves.