WeWork’s Perfect Storm

The company is buckling under the weight of its own hype and bad timing.

This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

Updated at 11:32 a.m. ET on November 7, 2023

WeWork, once the most valuable start-up in the country, is crumbling. Maybe it shouldn’t have gotten so big to begin with.

First, here are three new stories from The Atlantic:

Hype and Bad Timing

On its face, 2023 seems like the year WeWork was built for. Remote or hybrid work is common, and many companies are giving up long-term office leases. The time feels ripe for workers to flood into part-time, flexible WeWork rentals. But instead of flourishing, the company is buckling under the weight of its own hype and bad timing.

A decade ago, WeWork sensed that the way people worked was changing. The company’s smart, straightforward idea—to open co-working locations that freelancers and small businesses could rent space in month-to-month—collided with a frothy venture-capital moment that helped it grow explosively. On Tuesday, The Wall Street Journal reported that WeWork may file for bankruptcy as soon as next week, according to sources familiar with the company’s plans. WeWork’s stocks tumbled in response to the news. (A spokesperson for WeWork declined to comment on speculation but stated, “We have a clear, long-term vision for the future.” The company installed a new permanent CEO last month.) Bankruptcy would not mean that the company is dead. But it would be a striking setback for a once-powerful start-up.

WeWork, founded in 2010, wasn’t the first company to rent out co-working spaces, but it soon became the dominant one, capitalizing on the changes to work in the years following the Great Recession. These shared spaces were perfect for booming tech companies and the growing part-time and gig-based economy. WeWork solicited and received huge sums of venture capital that catapulted it to a multibillion-dollar valuation, and soon, it was opening facilities around the world. In 2019, it was for a time the most valuable start-up in America and was hiring 100 new employees a week. Then came management issues, followed by the pandemic. “WeWork combined two ideas—–one great and one terrible, and the terrible ended up sinking the great one,” Nick Bloom, an economics professor at Stanford, told me in an email. The great idea: building a business around flexible work. The terrible one: sinking billions into long-term leases on a huge volume of corporate office spaces. WeWork “got hit by a massive double whammy” of high interest rates and COVID-related hits to the office rental market, Bloom explained.

But WeWork’s problems began well before the commercial real-estate market cratered. The company’s co-founder Adam Neumann has become somewhat infamous for his antics: As Reeves Wiedeman, the author of Billion Dollar Loser, a book about the company, wrote in New York magazine in 2019, Neumann “can sound like a satirical version of a start-up founder … Spreadsheets are out; megalomaniacal ambition is in.” The Wall Street Journal reported that a flight crew once found a chunk of marijuana crammed into a cereal box on a private jet after Neumann and his friends got off the plane. And while he was CEO, the company acquired a family of “We” trademarks from a separate entity that Neumann controlled in exchange for nearly $6 million in stock (he undid the deal after pushback). Neumann’s attempt to take the company public in 2019 was disastrous; Wall Street balked at the company’s shaky financials—it was losing well over $1 billion a year at the time—and his potential conflicts of interest. After planning to debut with a value of $47 billion, the company deflated its valuation. Soon after, Neumann was pushed out of the company, and WeWork put its plans to go public on hold.

Executives from SoftBank—the Japanese company responsible for propping up some of the most overhyped start-ups of the past decade and a major investor in WeWork—installed a new CEO in February 2020. We all know what happened to office culture after that. Since then, the company has struggled to turn things around. It went public in 2021 through a special-purpose acquisition company, at a much more modest value of $9 billion. It has laid off workers, closed offices, and seen major turnover on its board and among its executive leadership.

WeWork framed itself as an innovative tech start-up, but it wasn’t actually a good fit for the rapid growth that venture-capital funding demands. Put ungenerously, it was a real-estate-rental company dressed up as a tech unicorn. Put more generously, it was an early innovator that anticipated the trend of flexible work, with a business model that made it too vulnerable to shifts in the rental market.

In the end, WeWork managed to take something people genuinely wanted and scale it up to a global level. But although hybrid work and flexible office spaces are here to stay, Bloom told me, WeWork’s competitors—including smaller, newer co-working spaces—are likely to reap the benefits of what it built. And the company’s size, though dazzling for a time, was part of the problem. Neumann used to say that WeWork’s mission was to “elevate the world’s consciousness.” Maybe turning a profit would have been a smart goal, too.

Related:

Today’s News

- FBI agents raided the home of Brianna Suggs, New York City Mayor Eric Adam’s chief fundraiser.

- Desmond Mills Jr. pleaded guilty to violating the civil rights of Tyre Nichols, who died in January after being beaten by police officers.

- President Vladimir Putin revoked Russia’s ratification of a global treaty that bans nuclear-weapons testing.

Evening Read

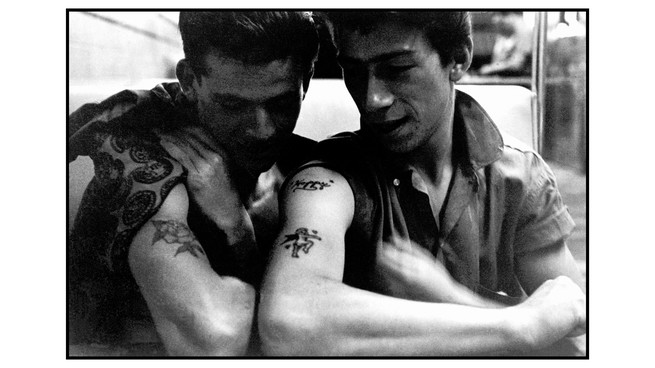

The New Meaning of Tattoos

By Annie Lowrey

Like a lot of Millennials, Sarah Curley has some tattoos. The public-health educator, who lives in Madison, Wisconsin, has a bouquet of wildflowers and the Greek word sophrosyne (meaning “temperance”) on her right wrist; some song lyrics on her ribs; and the phases of the moon on her inner left forearm.

Then, there is the 3 on the back of her neck, which represents her and her two sisters. In college, she went into a tattoo shop in Eau Claire, wanting a simply crafted number. “The artist—his style was very vivid, very detailed, and kind of on the macabre side,” she told me. Still, he was the guy available that day and she was impatient. “He did a good job—I mean, it was beautifully done,” she told me. But the tattoo ended up “thicker and more ornate than I would have designed for myself.”

At any other point in human history, that would have been the end of the story. Tattoos were forever. But in the past 10 years or so, tattoo removal has gone from being an expensive procedure performed by a dermatologist to something you can get done on a walk-in basis at your local strip mall.

More From The Atlantic

Culture Break

Watch. Netflix’s The Fall of the House of Usher really understands Edgar Allan Poe.

Listen. One man is working to keep the water on in Gaza. In the latest episode of Radio Atlantic, host Hanna Rosin shares her phone conversations with him as he struggles to find clean sources.

P.S.

If you have spent any amount of time at a WeWork location, you will be familiar with its distinctive metal cups emblazoned with the words “Always Half Full.” When I was at a WeWork for a previous job, I had an experience with such a cup that seemed to embody the late-2010s WeWork experience. I saw a tap of kombucha in the communal kitchen, filled a metal cup with the beverage, and swiftly drank it. Soon, I began to feel very relaxed and happy. I worked with alacrity, and then felt myself starting to become very tired. It turned out that I inadvertently drank a cup of hard kombucha, one of the random alcoholic beverages on offer there.

–Lora

In an eight-week limited series, The Atlantic’s leading thinkers on AI will help you wrap your mind around the dawn of a new machine age. Sign up for the Atlantic Intelligence newsletter to receive the first edition next week.

Did someone forward you this email? Sign up here.

Katherine Hu contributed to this newsletter.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

This article has been updated to clarify the nature of WeWork’s acquisition of “We” trademarks from an entity that Adam Neumann controlled.