What Life Magazine Taught Me About Life

As a child, I saw the country in its photos, stories, and advertisements—and learned some hard truths about America.

I grew up in the 1950s, on a farm in Virginia miles away from any town or neighbors. For most of my childhood we didn’t have a television, so my three brothers and I amused ourselves fighting pretend Civil War battles in the fields and woods around our house or vying over card and board games that we spread across the living-room floor.

But for me, the best entertainment was always reading. I read for pleasure, for company, and for escape from my contained Virginia world. I could explore other places and imagine myself into other lives—lives that went beyond the limited choices available to my mother and the women of her circle, who were all ruled by the era’s prescriptions of female domesticity. The written word introduced me to what girls could do: solve mysteries, like Nancy Drew; brave the Nazis, like Anne Frank; demand change, like the protagonist of Susan Anthony: Girl Who Dared. Reading could provide, to borrow Scout’s words in To Kill a Mockingbird, a way to escape “the starched walls of a pink cotton penitentiary closing in on me.” And words could carry me beyond the gentle slopes of the Blue Ridge Mountains that rose behind our house. They offered a view of national and global affairs that caught me up in a sense of urgency. I was frightened by the fact that Sputnik had been launched and was passing by overhead every 96 minutes in its orbit of the Earth. I wondered how the Russians had beaten us into space. I was inspired by the courage of Hungarians fighting against communism. I was reassured by portraits of the confident prosperity of postwar America. Yet I felt growing doubt and unease as I read descriptions of the turbulence and conflict emerging to undermine it.

We didn’t receive a regular daily newspaper. My father was in the horse business, so The Morning Telegraph—the bible of thoroughbred racing—appeared every day at the breakfast table. I was proud when he taught me to decipher the complicated “Past Performance” charts printed for every horse running that day, detailing previous outings, weight carried, split times, and race outcomes: win, place, show, or also ran. The Telegraph contained all the news one could want about the world of the track, but next to nothing about the world of public affairs.

We did receive lots of magazines. My father bought Playboy as a one-off, tucking copies into corners of bookcases around the house where we children inevitably found them. I remember poring over the contents, always astounded by the women in the centerfolds, who looked like no one I had ever encountered, clothed or otherwise. Most magazines, however, were placed in a wooden rack in the den, next to a comfortable overstuffed chair under the stairs. It was an inviting place to read, with an inviting library of publications. Sports Illustrated, The Saturday Evening Post, and The Chronicle of the Horse were regulars, as was The New Yorker, which lured me in with its cartoons, though more often than not I had to ask my parents to explain why one or another was funny.

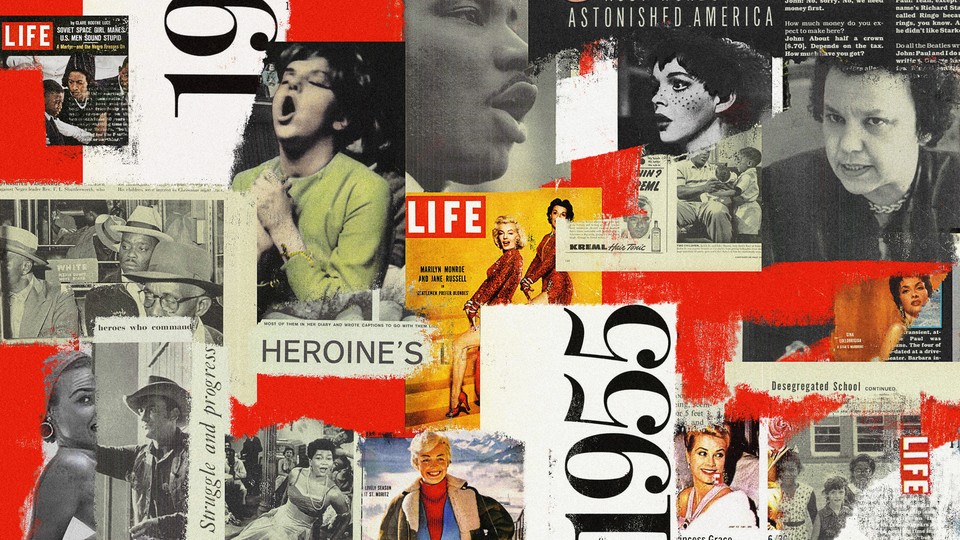

Above all, I read Life magazine. It’s hard to imagine, in today’s fragmented media environment, how any single source of information could reach more than a tiny fraction of the nation. In 1950, an estimated half of all Americans looked at Life every week. I was among them.

Returning to Life now, more than six decades later—looking through issue after issue covering the years of my childhood—I am struck by how the world of the 1950s it portrayed seems both so familiar and so strange. Davy Crockett coonskin hats, Hula-Hoops, pogo sticks, Elvis—Life chronicled crazes that reached even to rural Virginia. I recognize nearly every product pitched in the dozens of pages of advertising that filled each issue of the magazine, even though many of the products have not existed for years. The back cover of most issues displayed a full-page cigarette ad—for Lucky Strikes (“Cleaner, Fresher, Smoother”) or Camels (“It’s a psychological fact that pleasure helps your disposition! That’s why everyday pleasures—like smoking, for instance—mean so much.”) One news story Life published about childbirth depicted a woman smoking during labor. This startles me now, but back then I took for granted a home filled with clouds of smoke from my mother’s daily pack of Camels and my father’s cigars.

Multipage spreads in the magazine presented the newest models of enormous cars, designed, like our family station wagon, to transport all those Baby Boom children. These ads featured vehicles that were lavishly finned and often stylishly two-toned, though by the end of the decade smaller models such as the Nash Rambler, the Ford Falcon, and even the VW Beetle had begun to mount a challenge.

The food that appeared in Life now seems almost unimaginable.

A soda ad urged parents to add 7Up to babies’ bottles in order to coax them to drink their milk (suggested proportion: half and half). Another ad proclaimed the advent of National-Use-Up-Your-Leftovers-in-a-Jell-O-Salad Week. For an elaborate Southwest barbecue, “everything, even the meat, comes from cans.” In the mid-1950s, the average American family ate 850 cans of food annually. A special issue on food in January 1955 extolled “the servants who come built into the frozen, canned, dehydrated and precooked foods which lend busy women a thousand extra hands in preparing daily meals.” These busy women were perpetually in a hurry and would welcome such innovations as instant oatmeal, instant coffee, and Swanson’s TV dinners.

Life chronicled the emergence of aspects of contemporary existence that I tend to think of as present since the beginning of time. This was the decade when credit cards entered American life. The Interstate Highway System was launched in 1956. Passenger travel by jet began in 1958. In the first part of the decade, Life reported airplane crashes with disturbing regularity, perhaps because, astoundingly, air-traffic control existed only near airports, and pilots themselves were responsible for spotting other planes when they weren’t taking off or landing. When two pilots failed at this assignment over the Grand Canyon, in 1956, and 128 people died, the FAA at last took over responsibility nationwide. It is not surprising that my mother hated to fly and did her best for years to have her children avoid air travel.

If I had read Life in search of models for my adult life, I would have been hard-pressed to find much that was encouraging about what lay ahead. Every third or fourth cover featured a glamour shot of a woman—almost always an established or emerging movie star: Shelley Winters in a tub of bubbles, “Lovely Liz Taylor,” Joan Collins on a swing, Sophia Loren, Audrey Hepburn, Kim Novak. Such lives were clearly unattainable—and, to my mind, of little interest. Other kinds of stories about women were scarce and overwhelmingly reflected an unease with who American women were becoming. In 1955, an article titled “The 80-Hour Week” described housewives as the nation’s “largest, hardest working, least paid occupational group.” The middle-class white woman featured in the article did not overtly complain about her burdens, but her words conveyed a kind of stunned desperation. “I just wish I was away on a long trip,” she remarked.

In December 1956, Life published a special double issue on “The American Woman: Her Achievements and Troubles.” Once again, the focus was exclusively on middle-class white women, with an opening story about American “beauties” who hailed their derivation from “many racial stocks”—such as German and Scandinavian. The new freedoms that women enjoyed in postwar America, one contributor concluded, had created a “backwash” of “emotional and psychological problems.” As the issue’s editorial observed, the “American woman is often discussed … as a problem to herself and others.” Life seems to have been anticipating Betty Friedan’s classic, The Feminine Mystique, by nearly a decade.

I hope my childhood self skipped over these stories as I paged my way through the magazine. They could only have filled me with dread. Perhaps, though, I stopped to look at one article with a more inspiring message and direct relevance to my later life: “Tough Training Ground for Women’s Minds; Bryn Mawr Sets High Goals for Its Girls.” The college, according to the article, offered “some of the most intensive intellectual training available in any college in the U.S.” Nearly a decade later, Bryn Mawr would offer me a lifeline.

It was in many ways highly forward-looking of Life to offer such recognition to women—and, more especially, to acknowledge their discontent. One disgruntled reader assailed the editors for even taking up the subject. “Bah! With the world situation being as it is … you clutter up 172 pages of Life with women.” Life in fact regularly cluttered up dozens of its pages with women—promoting cars, appliances, beauty products, and fashion in the ads that filled the magazine. Of course, these women were not dissatisfied housewives but exuberant consumers. Such a portrait sat more easily with Life’s readers than any effort to look beneath the surface of the myths about gender.

Throughout the 1950s, countless advertisements in Life displayed women encased in girdles—like Playtex’s aptly named “Magic-Controller”—and featured elaborately engineered bras as well as a diabolical apparatus first introduced in 1952 called a Merry Widow. The contraption extended from breasts to girdle top, ensuring that no flesh could escape appropriately corseted discipline. The doctrine of “containment” that had made its appearance as a watchword of U.S. foreign policy seems to have had its counterpart in feminine fashion. Men’s bodies were not subjected to such restraint, but their “unruly” hair required attention. Vitalis hair tonic promised to restore order, casting its oil upon waves of curls or windblown locks.

Pale pink, proclaimed “fashion’s favorite color” in 1955, was everywhere: cars, stoves, typewriters, washing machines, refrigerators, toilets, bathtubs. Mamie Eisenhower was pink’s greatest champion, introducing it into the White House—“First Lady Pink” was the particular hue—as well as in plumbing fixtures in her own Gettysburg house. In my mind, pink was the color that marked girls as frail and sweet and irrelevant. Not unlike a girdle or a Merry Widow, pink seemed intended to contain.

Life’s pages of advertisements were an advertisement for America, its abundance and its complacency. Complacency was reflected in much of the magazine’s news content as well. Americans in the 1950s, the magazine editorialized, were “mightily pleased with themselves.” But who were the Americans Life addressed and portrayed? With the exception of a butler serving a drink on a silver tray, every individual pictured in the hundreds of Life ads I’ve seen from the 1950s was white.

The magazine’s news stories exhibited more variety. Life regularly featured Black athletes and entertainers. Marian Anderson, Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte, W. C. Handy, Floyd Patterson, Bill Russell, Sugar Ray Robinson, Althea Gibson, and Willie Mays occupied categories in which mid-century white America had come to acknowledge Black achievement. In the course of the decade, the magazine began covering other Black Americans as well, but these stories were neither appreciations nor celebrations. Instead, they were focused on what was often called “the Negro Problem”—how Black people constituted a crisis in American life and a challenge to the idealized images of American democracy and prosperity that the magazine consistently foregrounded.

Starting with the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, Life demonstrated steady support for the civil-rights movement, even as it sought to present the variety of positions in the escalating national debate about race. Voices of white southerners who opposed integration or thought it should not be mandated by federal courts were given serious attention. Life even enlisted William Faulkner to warn the nation: “Go slow now. Stop for a time, a moment.” The white southerner, Faulkner observed, “faces an obsolescence in his own land which only he can cure.” But Life’s gestures at what it prized as objectivity and evenhandedness appeared alongside a clear commitment to Black progress and equality, evident in both editorial and news content. From 1954 to 1956, Life published 46 articles about civil rights, filling 160 pages of the magazine. Overwhelmingly, these chronicled the stories of Black efforts to advance integration and the ensuing white backlash of cruelty and violence—from racist schoolyard taunts to bombings, beatings, and lynchings.

In 1956, the magazine published a five-part series on segregation, introduced with a dramatic and disturbing cover illustration depicting an antebellum Charleston slave auction. Life’s rendering of the nation’s past was remarkably critical in the context of both its time and its middlebrow identity; the magazine avoided any romanticized or sanitized version of America’s racial history. Disturbing portraits of the nation’s past included illustrations of Confederates shooting wounded Black prisoners during the Civil War, white people slaughtering Black people seeking political rights in Louisiana’s 1873 Colfax massacre, and a horrifying photograph from the early 20th century of a Black man being burned alive by a crowd of jeering white men.

These were not stories regularly told in the era’s history books. But they were images that riveted my attention, because the world they portrayed differed so markedly from the narrative of benevolent white paternalism and genteel racial harmony that I had absorbed since my earliest childhood. And they contrasted sharply with Life’s own prevailing assumptions about 1950s America as a nation “up to its ears in domestic tranquility.” Contradictions like these and the denial on which they fed pushed me to question the assumptions of the world around me and the lessons I had been taught. I resented what I began to perceive as the blindness or even bad faith of those who had misled me. This generated the tone of indignation and surprise in a letter I wrote to President Dwight Eisenhower—“Mr. Eisenhower,” I called him—on three-holed notebook paper in 1957. “I am nine years old and I am white, but I have many feelings about segregation,” the letter began—so I discovered when I found the letter years later in the Eisenhower presidential archives, in Abilene, Kansas. “Please Mr. Eisenhower,” I entreated, “Please try and have schools and other things accept colored people.” How could I have not known why my school was all white? How could I have been taught about the ideals of American democracy and Christian love when such terrible injustices did not just exist but were so vigorously defended, often by the very same people mouthing civic and religious pieties?

Life was not merely recounting a distant past. In nearly every issue during the mid-1950s, the magazine confronted readers—in shocking photographs as well as words—with a new set of outrages, events never mentioned by my parents or teachers. Stories depicted the murder of Emmett Till in 1955, the lynching of Mack Parker in 1959, and the assaults on Black students seeking to integrate schools in Little Rock, Charlotte, Greenville—and even in the Virginia county adjacent to ours. In Life’s pages, I encountered Black boys and girls close to my own age, including a number seeking to attend schools not far from my own home. I could see Black children, sometimes even younger than I was, bravely facing angry mobs as they seized a right I could simply take for granted.

Life had shown me photographs of Hungarian children risking their lives in the 1956 revolution, thousands of miles away. Books had introduced me to “girls who dared” in other eras and other places. But now children of my generation, children in my state of Virginia, were creating their own heroic stories. It was not the Montgomery Bus Boycott or the Mack Parker lynching or the 1957 Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom in Washington—all of which were fully reported on in Life—that moved me to write to Eisenhower. It was school integration. I identified and empathized with these girls and boys. In many ways, the civil-rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s originated as a children’s crusade, a designation later explicitly used by civil-rights leaders when children—some as young as 6 or 7—filled the streets and jails of Birmingham, Alabama, in the summer of 1963. Half a decade earlier, the courage of such young people seeking justice had both inspired me and filled me with a sobering sense of responsibility.

What I was reading was more than stories. This was about how it might be possible—and even necessary—to live a life.

This article was adapted from Drew Gilpin Faust’s book, Necessary Trouble, published this month by Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.