What My Dad Gave His Shop

“I’m more than just my store,” my father told me. And yet, for nearly his entire adult life, all of his decisions had argued the opposite.

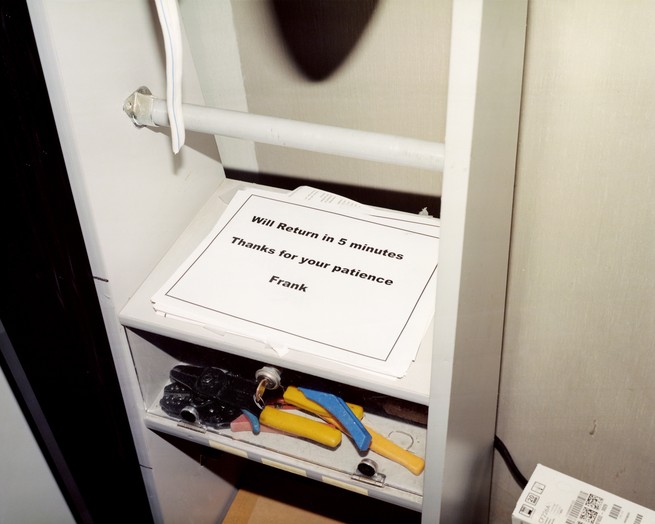

The first time I looked at my father’s Yelp reviews, I choked up. They were not all positive, and of course I read the worst ones first. My dad, Frank, runs a high-fidelity audio-video store in San Francisco and also repairs the brands he sells. One reviewer gave him one star, noting that his turntables had sat in the shop for five weeks, untouched. It brought me back to all the school nights when we stayed at the store until 9 p.m. so he could finish a job that was overdue. Another guy complained that when he called, my dad picked up blurting, “What do you want? I’m vvvvvveeeerrrryyyy busy.” I remember hearing him do that once when I was a kid. He was on hold with the bank or a supplier, and the second line kept ringing. I was aghast. “Well, I hope you are sooooooooo busy that people do not EVER go to your store,” this reviewer wrote.

But the haters were in the minority. His clients included George Moscone (“very down-to-earth,” my dad said) and Walt’s daughter Diane Disney Miller (“short like Minnie Mouse and kind to everyone”). “Frank is the man!!” one customer wrote. “He is the only one I believed I could trust with a delicate and expensive job—and boy was I right.” “Will try to find good value for someone who isn’t a cognoscenti about audio,” another said. “Been going to him for 30 years. Never would go anywhere else.” A “neighborhood gem.”

And then there was a review from someone who hadn’t bought a thing from my dad. He’d locked himself out of his car and wrote to thank my dad for letting him use the store’s phone. Would an employee at Walmart do that? Could they? Big-box stores are designed such that the workers rarely see the outside. They aren’t part of “the ballet of the good city sidewalk” that Jane Jacobs wrote about in The Death and Life of Great American Cities. In the mid-century Greenwich Village that she immortalized, grocers held keys and packages for neighbors, and candy-store clerks kept an eye on kids. Even the drinkers who gathered under the gooey orange lights outside the White Horse Tavern kept the street safe by keeping it occupied. When I first read the book 15 years ago, I told my dad to pick up a copy, which he diligently did, from the bookshop up the street. It was the first book he’d read since he started at the store, in 1975.

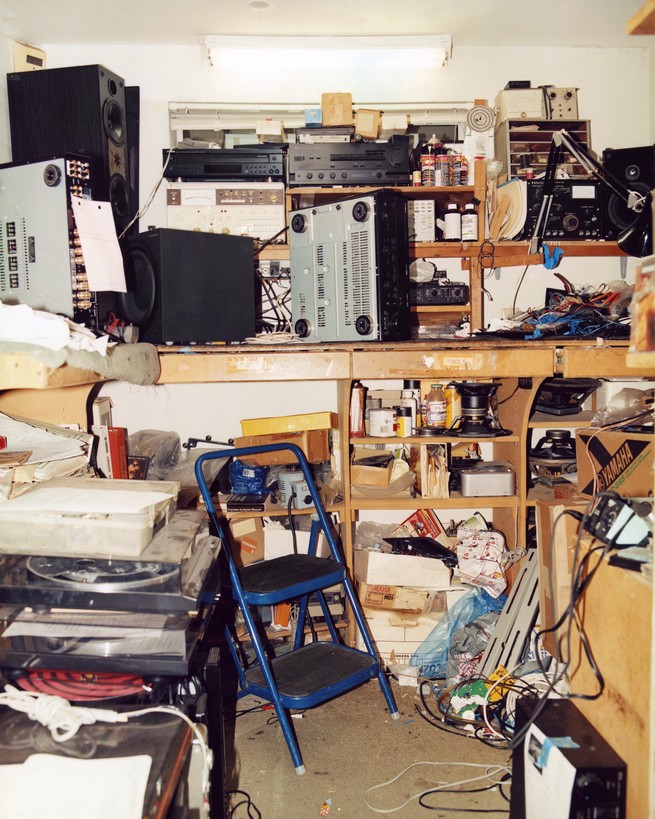

In the late ’60s, my dad would gather his high-school friends in his bedroom in San Francisco to play with different turntables. After they left, he’d Windex their fingerprints off the cabinets and glass, a habit that his mother proudly reported to her friends. In his spare time, he took things apart and put them back together—clocks, radios, amplifiers—and to support himself during college, he got a repair job at an audio-video store. He wanted to be a radio DJ, and he hosted a weekly show for the College of San Mateo’s NPR affiliate. But when I ask him what he played, he can’t remember. The station allowed only “middle-of-the-road music.” And for him, the sound quality was just as important as the artists.

He moved from the repair room at the audio-video store to the sales floor—a somewhat pompous description of a 15-by-25-foot room with sea-foam-colored carpet and soundproof sliding-glass doors. One day, a nurse walked in and he sold her a VCR. He called her a couple of times to ask if it worked okay and then finally asked her out, to the Dickens Fair (where everything—and everyone—is out of a Charles Dickens novel). His sister worked there and had comped him a couple of tickets. Seven years later, that nurse, who was seven years older than my dad, gave birth to me. In the late ’80s, Frank became a co-owner of the store, and in the ’90s, he bought out the founder.

For 45 years, that store, Harmony Audio Video, has been my dad’s life: the reason he left home early every day, the reason he was chronically late to pick me up from school, the reason he didn’t take a single vacation for 25 years. Growing up, the store was my life too: From the time my mom’s breast cancer metastasized when I was in second grade (she died when I was 10), I hung out in the back after school until 7 or 8, before we drove 40 minutes home on coastal Highway 1 to slightly more affordable El Granada. Keeping me with him at work meant he didn’t have to pay for child care. In exchange, he basically ceded the store’s second phone line to me for conversations with classmates and friends. If he was with a client and I had a question, I had to write it on a note card—one of the hundreds of blank neon mailers on which he listed monthly specials.

The store put me through private school in San Francisco (with an assist from financial aid). And it got me a summer job pipetting chemicals into test tubes in high school (a scientist at a blood lab was one of his customers). I’m not going to say the store was a community linchpin—nobody needs really nice speakers or crystal-clear flatscreen TVs—but it was a node through which different strata interacted: doctors, tech VPs, working-class Italians from North Beach like my dad, who were into fast cars and fancy speakers, as well as the musicians and video guys he employed and for whom he set up profit-sharing plans.

That nobody needs speakers and TVs was something I was righteous about as a kid. The deluxe education that my mom sought out, and my dad proudly supported, produced an insufferable 12-year-old. Television, I’d determined, was a waste, and I took every opportunity to tell my father that what he was doing was, well, nonessential, as we might now say. At one point, my dad told me that I shouldn’t feel any pressure to one day take a job at the store, which was touching because it was so abundantly clear that I never would. My mom always wished that she’d done something other than nursing, and I knew he wanted me to find a career I loved.

What my dad also didn’t need to say was that he liked his work. He loved sitting a customer down in the Eames-knockoff recliner in the sound room and blasting music or a movie—Terminator 2, Independence Day, The Rock—in surround sound, subwoofer rumbling. This was the soundtrack of my childhood. He relished equipment that faithfully generated the geometries of noise, prickly sounds and round ones, sharp sounds and sonorous ones. He read Stereophile and other trade publications cover to cover, invested in new products, learned how they worked. He was quick to adopt technologies that would later become ubiquitous: CDs, DVDs, Bluetooth, streaming, Sonos. (Not every bet paid off. Remember laser discs? He has cabinets full of them.) The advantage and disadvantage of a business like his is that the technology is always advancing, giving customers something to chase but leaving the owner always running to catch up.

I suspect the other reason for my reflexive resistance to the store is that it made me a witness to my dad’s vulnerability. In the early 2000s, when I was in high school, he aimed to sell an average of $2,000 worth of equipment a day—and he did. But “average” meant good days and bad ones. Occasionally, a doctor bought an entire custom home-theater system after perusing for an hour. Other days, a lawyer would ask dozens of questions before declaring that he was heading to Best Buy. Or Lou Reed might walk in, insult the Tchaikovsky playing over the speakers, buy $700 Grado headphones for a recording session at Skywalker Ranch, and then have an assistant return them once it was done. Sundays and Mondays, his days off, were the slowest. Too often, he’d call in and learn that not a single sale had been made.

It hadn’t always been this way. My dad started at the store during the heyday of performance audio. Certain high-end lines were sold only through authorized dealers, whom the companies paid to educate. Yamaha sent my dad to the Bahamas and B&W sent him to its factory in England, a trip that remains one of his fondest memories. He took my mother—there was a tourist program for significant others, almost entirely women. Before the internet, high-fidelity audio-video companies coordinated with countless independent dealers. After the internet, which multiplied the possible paths to consumers, not so much. The last conference my dad attended was in Phoenix, in the mid-’90s. He brought back a bonsai cactus, which, 20 years later, is thriving—unlike anything else in the industry.

If you listened to American politicians, you might think the government lavishes support on small businesses. But that has long been more rhetoric than reality. The last time robust federal legislation boosted independent retailers was in the mid-1930s (and whether it was actually good policy is another question). The Robinson-Patman Act prohibited growers, manufacturers, and wholesalers from giving discounts to chains for large-quantity purchases, even though those savings were often passed on to consumers in the form of lower prices. “There are a great many people who feel that if we are to preserve democracy in government, in America,” Representative Wright Patman declared, “we have got to preserve a democracy in business operation.” Shortly thereafter, Congress passed another pro-small-business law, forbidding predatory pricing—selling goods at gross discounts to quash the competition.

Yet the price-setting legislation mostly failed, because large merchants simply stocked slightly different products. It also led to the rise of sophisticated corporate lobbying. In 1938, Patman proposed a graduated federal tax on retailers operating in multiple states. In response, the grocery chain A&P—later accused of predatory pricing—ran ads in 1,300 newspapers denouncing the tax and emphasizing its low prices. The bill died.

The same year, President Franklin D. Roosevelt hosted a conference in Washington, D.C., for 1,000 small-business owners, hoping to gain their backing for the New Deal. But the beauty of the small-business owner—a stubborn, sometimes radical independence—was also a political weakness. It was impossible to get the group to reach consensus on anything.

The number of small businesses would ebb and flow in the decades that followed. But since the 1960s, courts hearing antitrust cases have tilted in favor of ensuring low prices for consumers rather than preserving competing companies’ access to the market. From 1997 to 2007, the revenue share of the 50 largest corporations increased in three-quarters of industries. Low prices might sound great, but the result, compounded over half a century, is economic inequality so stark that many workers are too poor to afford them.

Best Buy was once my dad’s No. 1 nemesis. Every Monday, the only day we drove straight home after school (it being one of my dad’s days off), we passed the huge blue box via the Central Freeway. My dad almost always made a snide comment about “built to break” electronics and harried employees. Nonetheless, working 12 hours a day, he could still take home close to $100,000 a year in the early 2000s.

Then came the iPhone and the ubiquity of online shopping. The internet wasn’t all bad for my dad. It enabled him to get outdated parts on eBay and to search audiophile forums for tips on tricky repairs. With a few clicks, he could also see the big-box stores’ prices and endeavor to beat them. But many consumers were content to stream music on their laptop, as tinny as the sound might be. And generally, the industry began to tilt more heavily against small retailers. Amazon amassed power, sowing an expectation of overnight shipping and ultralow prices—though the bargains often didn’t last. (“I looked up web prices as a point of comparison and found Harmony’s pegging most prices at a dollar less than what Amazon’s asking,” one customer wrote on my dad’s Yelp page.) Amazon’s real triumph is a monopoly not on pricing but on our imagination.

For 35 years, Harmony was open seven days a week, but in the years after the Great Recession, Frank decided to close on Mondays, and eventually Sundays too. His full-time employees slowly peeled off. One retired and another moved into film editing; my dad didn’t replace them. When I was growing up, it was rare for anyone to run the store alone. Over the past decade, it’s become the norm. A retired friend of my dad’s comes in to help and hang out, billing just for the hours he’s needed. The only thing that’s made my dad a bit of money is custom installation—emphasis on a bit. Postindustrial America is a service economy; there are the rich and those who serve them. Last year, in San Francisco, a city flush with tech wealth, my dad paid himself only $12,000, preferring to reinvest in the store and dip into his retirement funds to pay his bills.

So things were already tight when the pandemic hit. On March 17, the Bay Area became the first region in the U.S. to institute a shelter-in-place order, breaking my dad’s 45-year routine—for his safety. But he couldn’t stop himself from driving to the store almost every day, which was allowed because repair work was considered an essential service. He kept the lights off and the front door locked and went to the back, where he tinkered with soundboards and soldering equipment.

After applying for the first round of Paycheck Protection Program funding, my dad learned that the government had run out of funds. Administered by major banks, the program tended to favor the large corporations they’d already worked with. Harvard University, Ruth’s Chris Steak House, Shake Shack, and various hospitality companies controlled by the Trump megadonor Monty Bennett got tens of millions from the first distribution; countless small businesses were told there was no money left. (These big organizations returned the funds, tail between legs, only after public outcry and refinements to federal regulations to prevent this kind of exploitation.)

Adding insult to injury, Congress used the CARES Act, which instituted the PPP loans, to pass $174 billion worth of tax breaks that had long been on real-estate-developer, private-equity, and corporate wish lists. “There is no real public-interest lobby on these kind of obscure corporate tax provisions,” the New York Times reporter Jesse Drucker told NPR’s Terry Gross at the time. Only a small number of tax lobbyists even understand them. This was just one more example of a system that’s come to favor the big over the small.

Throughout the pandemic, my dad has continued to pay the few people left on his payroll, including a former salesman who writes a lively biweekly newsletter (complete with a movie review!). Otherwise, his overhead was low. Still, 60 days into the pandemic, he realized that the store would run out of money by the end of the month.

He considered applying for the second PPP distribution—but he was overwhelmed by the information requested and the changing rules. (So were others. Four hours before the program would have closed on June 30, with small businesses still suffering but with $130 billion unspent, the Senate extended the application deadline by five weeks.) In mid-May, my dad, who has never been a reasonable man, reasonably said, “I’m one of the last performance-audio guys. Why am I going to bang my head against the wall like an idiot? It’s time to go bye-bye.” At the age of 68, he filed for Social Security and told me he was preparing to close for good.

I’d pleaded with him to consider retiring for the past couple of years, but now, as he told me his decision over the phone, I struggled to keep my composure. Looked at a certain way, my dad was one of the lucky ones. He’d contributed to retirement accounts and was of retirement age. Yet it felt like an ignoble end to four and a half decades of work. “I’m more than just my store,” he told me. And yet, for nearly his entire adult life, all of his decisions had argued the opposite.

Then, on Monday, June 15, San Francisco permitted indoor retail to reopen, following safety protocols. My dad was closed Mondays, but he couldn’t miss the grand opening, so he worked six days straight, no pay. (He hadn’t cut himself a check from the store since January.) His instincts were good. Wireless speakers had been selling out during the pandemic, but he had plenty in stock, and people a little older than me, my dad said, were keen to support a local store. His loyal customers—people he has known for decades, people whose kids, careers, and concerns he takes an interest in—delighted my dad by dropping in, mask on, hair long, some almost unrecognizable, telling him they wouldn’t buy anywhere else.

More than 400,000 small businesses have closed since the start of the pandemic and many thousands more are at risk, according to the Brookings Institution–affiliated Hamilton Project. Mom-and-pop stores across the country are liquidating, breaking their leases, putting up handwritten goodbyes. “We are sad and sorry that it is time to say zai jian (until we meet again),” read a sign at San Francisco’s dim sum institution Ton Kiang. “Over the years, you shared your weddings and anniversaries with us, celebrated and had us host your life passages and family gatherings … We will always treasure these moments and value your friendship.”

How many of these businesses will eventually be replaced, and what will be lost if they aren’t? It’s easy to compare prices. It’s harder to put a value on the cranky independence of small-business owners, or their collective importance to community spirit and even the American idea. “What astonishes me in the United States is not so much the marvelous grandeur of some undertakings as the innumerable multitude of small ones,” Alexis de Tocqueville wrote in 1835.

My dad, so happy to be back, acted like he’d never told me that he was folding up shop. He was in retail (bad), but the products he was selling were for the home (good). For now, for at least a little while longer, he’d be cranking up the volume in the sound room, where he belonged.

This article appears in the December 2020 print edition with the headline “Death of a Small Business.”