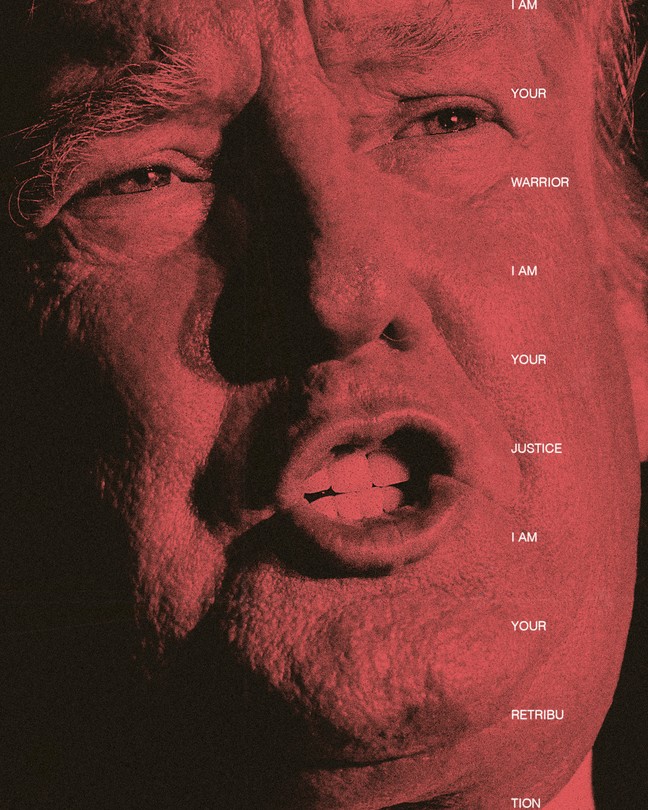

What the 2024 Election Is Really About for Trump Supporters

He promised them: “I am your retribution.”

Updated at 9:15 p.m. ET on November 2, 2023

This article was featured in One Story to Read Today, a newsletter in which our editors recommend a single must-read from The Atlantic, Monday through Friday. Sign up for it here.

Twenty‐five years before my first book about Donald Trump was published, I wrote a paperback titled The Right to Bear Arms: The Rise of America’s New Militias. It was written after Timothy McVeigh’s 1995 bombing of the Oklahoma City federal building, and tracks the emerging anti-government movement that inspired McVeigh to make war on the federal law-enforcement agencies that he, and many other far‐right activists, believed posed a threat both to America and to themselves.

On the cover of the book is a photograph of the Branch Davidians’ Waco, Texas, compound engulfed in flames. Federal law enforcement learned that the group was stockpiling weapons and explosives and, after a disastrous siege in early 1993, attempted to storm the compound. With agents closing in, several Branch Davidians set fire to the building, apparently preferring to die rather than be captured by authorities. The body of the cult’s leader, David Koresh, was found with a gunshot to the head.

The raid was a colossal failure. To some, though, the debacle represented something far more sinister: a deliberate plot by the government to trap and murder the Branch Davidians.

Waco became a rallying cry for right‐wing activists who believed that Washington, D.C., was out to get them. “Citizens’ militias” stockpiled arms and ammunition as well as food and survival gear. Some played weekend war games in vacant parking lots, on farmland, or in remote woodlands. “The ranks of the militias are made up of factory workers, veterans, computer programmers, farmers, housewives, small‐business owners,” I wrote in the book’s introduction. “The most shocking thing about these ‘paramilitary extremists’ is how normal they are. They are your neighbors. But in another sense, many members of America’s new militias live in a parallel universe, where civil war is already being waged by tyrants within the federal government.”

In the run‐up to publication, I planned a small party and decided to spruce up the invitation with some over‐the‐top words of praise from my friends and colleagues. A couple of my colleagues at the New York Post offered up some choice words, and on a whim, I decided to call a famous New Yorker who was both a reliable source and known for making hyperbolic statements to see if he would give me a quote as well. He readily agreed to provide a glowing endorsement—provided I wrote it up myself. So I did:

“What a book! Karl is one of the best in the business—tough, fair and brutally honest.” — Donald J. Trump

Trump signed off on the quote. To this day, I don’t know whether he actually read the advance copy of The Right to Bear Arms I sent him—but more than a quarter of a century later, he announced that the first rally of his 2024 presidential campaign would be held in a familiar location: Waco, Texas.

Largely irrelevant in both the Republican primary and the general election, Texas was an odd choice for the campaign kickoff. A Trump spokesperson would later deny that the venue selection was at all related to the massacre that took place there almost exactly 30 years earlier—he claimed Waco was chosen solely because it was “centrally located” and “close” to big cities such as Dallas and Houston—but plenty of rally attendees drew the connection between the setting and Trump’s central campaign message.

“[Trump’s] making a statement, I believe, by coming to these stomping grounds where the government, the FBI, laid siege on this community just like they laid siege on Mar‐a‐Lago and went in and took his stuff,” Charles Pace, a Branch Davidian pastor who knew Koresh but left the compound several years before the deadly fire, told The Texas Tribune. “He’s not coming right out and saying, ‘Well, I’m doing it because I want you to know what happened there was wrong.’ But he implies it.”

Shortly after the rally was announced, I asked Steve Bannon, who had served as the CEO of Trump’s 2016 campaign and had once again emerged as one of Trump’s most important advisers, why the former president would go to Waco for his big campaign reboot. He wasn’t coy.

“We’re the Trump Davidians,” he told me with a laugh.

Even less subtle than the venue of the rally was how Trump kicked it off, standing silently onstage with his hand on his heart while he waited for “The Star‐Spangled Banner” to play. This wasn’t a traditional version of the national anthem. Trump’s campaign had queued up “Justice for All,” a rendition of the song recorded over a jailhouse phone by a group of about 20 inmates being held in Washington, D.C., for taking part in the assault on the U.S. Capitol. In the song, the so‐called J6 Prison Choir makes its way through Francis Scott Key’s lyrics while Trump’s voice interjects with stray lines from the Pledge of Allegiance, which he recorded at Mar‐a‐Lago. As the recording blared, video footage from the January 6 riot played on the massive screens flanking the stage.

“For seven years, you and I have been taking on the corrupt, rotten, and sinister forces trying to destroy America,” he told the crowd. “They’re not going to do it, but they do get closer and closer with rigged elections.”

He declared, “2024 is the final battle.”

This wasn’t a campaign speech in any traditional sense. Trump echoed the themes of paranoia and foreboding that grew out of the Waco massacre. “As far as the eye can see, the abuses of power that we’re currently witnessing at all levels of government will go down as among the most shameful, corrupt, and depraved chapters in all of American history,” he said.

“They’re not coming after me,” he told the crowd. “They’re coming after you.”

The message seemed to resonate, but its brazenness was staggering. The folks cheering Trump had not taken boxes stuffed with classified documents out of the White House—and it’s safe to assume that none of them spent tens of thousands of dollars to cover up an affair with an adult‐film star.

Whatever you think about the investigations, Trump invited the scrutiny. Special Counsel Jack Smith was probing Trump’s role in the January 6 attack and his failure to turn over that classified material. Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis was investigating his efforts to overturn the 2020 presidential-election results in Georgia. And Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg was nearing an indictment on charges related to hush‐money payments Trump made weeks before the 2016 election to the porn star Stormy Daniels.

“The DOJ and FBI are destroying the lives of so many Great American Patriots, right before our very eyes,” Trump posted on Truth Social the day after four members of the Proud Boys militia were convicted of seditious conspiracy for their role in the storming of the Capitol. “GET SMART AMERICA, THEY ARE COMING AFTER YOU!!!”

But “they” weren’t coming after Trump’s law‐abiding supporters—they were coming after Trump. Decades earlier, the presidential candidate Bill Clinton told voters that he felt their pain. Trump was now doing the reverse, trying to persuade his supporters to feel his pain as if it were their own.

Trump was in a dark place when he announced that he was running for president in early 2023. Still reeling from the Republican Party’s disappointing midterm performance the previous November, he barely seemed to be trying. A close confidant of the former president told me that he was trying to get Trump to do more to jump‐start his effort to win back the White House, encouraging him, for example, to go on the attack against President Joe Biden and the Democrats over the federal bailout of Silicon Valley Bank. But the adviser was getting nowhere. “He’s just obsessed with this New York thing.”

The “New York thing,” of course, was Bragg’s grand-jury investigation. The case was long believed to be dead, but on January 30, the Manhattan D.A.’s office had impaneled a new grand jury and begun presenting evidence of Trump’s involvement in the hush-money payments. Over the next few weeks, it became clear that the first presidential indictment in history was imminent—but nobody knew exactly when Bragg would pull the trigger.

Except, apparently, Donald Trump.

“THE FAR & AWAY LEADING REPUBLICAN CANDIDATE & FORMER PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, WILL BE ARRESTED ON TUESDAY OF NEXT WEEK,” he posted on Truth Social at 7:26 a.m. on March 18.

Political journalists scrambled to find out what Trump was talking about. Why hadn’t anybody tipped them off that such momentous news was coming? Had Bragg officially communicated to the former president’s legal team what to expect? How else could Trump have been so confident about the exact date of his arrest?

One of Trump’s lawyers, Joe Tacopina, would later tell reporters that the former president’s legal team had not been informed of any impending indictment—and he was right. So where did Trump get the idea he was about to be arrested?

A source close to Trump told me that the former president had learned of his pending indictment from an MSNBC show called Morning Joe: Weekend. Not that many people are tuning in to a cable-news program that starts at six on Saturday mornings, but Trump was, and he took particular interest in a segment—a rerun from two days earlier—featuring the legal analyst Andrew Weissmann on the Manhattan D.A.’s investigation. Discussing Bragg’s recent interactions with Trump’s legal team and the grand jury, Weissmann said he couldn’t see the D.A. not indicting the former president, telling the show’s co-host Joe Scarborough that he believed such a move was imminent: “We should be very, very conscious that this is likely to come down very soon.”

Trump, according to my source, interpreted Weissmann’s speculation as fact. “IT’S TIME!!!” Trump wrote on his Truth Social platform. “THEY’RE KILLING OUR NATION AS WE SIT BACK & WATCH. WE MUST SAVE AMERICA! PROTEST, PROTEST, PROTEST!!!”

Trump’s rhetoric was reckless—recall what happened the last time he encouraged his supporters to protest—and it prompted a flurry of news coverage and political commentary on his alleged criminality. That might seem problematic for somebody trying to get a presidential campaign off the ground. But everyone seemed to be talking about him again, and Republicans—even his potential 2024 rivals—felt obligated to jump to his defense, or at least condemn the Manhattan D.A. To Trump, that was a win.

In the days following his prediction of a Tuesday arrest, he attacked Bragg, who is Black, as a “Racist in Reverse” and “degenerate psychopath” who was pursuing him while letting “MURDERERS, RAPISTS, AND DRUG DEALERS WALK FREE.” Trump’s most inflammatory comments were about what would happen to the country if Bragg went through with what he was planning. “What kind of person can charge another person,” Trump wrote on March 24, “when it is known by all that NO Crime has been committed, & also known that potential death & destruction in such a false charge could be catastrophic for our Country?”

The implication seemed clear: Drop the case against me, or my supporters will get violent. That same day, an envelope—apparently mailed from Florida—was found in the Manhattan D.A.’s office containing a trace amount of white powder and a letter that read, “ALVIN: I AM GOING TO KILL YOU!!!!!!!!!!!!!”

For a few days at least, Trump believed that his threats had had their intended effect. Tuesday came and went, and he remained a free man. So did Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday. By Saturday, Trump was talking as though he had successfully outmaneuvered Bragg. “I think they’ve already dropped the case,” he told reporters on the plane ride back from his campaign rally in Waco. “It’s a fake case—some fake cases. They have absolutely nothing.”

When multiple news outlets reported on March 29 that the grand jury would be taking a month-long hiatus, Trump was ecstatic. “I HAVE GAINED SUCH RESPECT FOR THIS GRAND JURY, & PERHAPS EVEN THE GRAND JURY SYSTEM AS A WHOLE,” he posted on Truth Social. “THE EVIDENCE IS SO OVERWHELMING IN MY FAVOR, & SO RIDICULOUSLY BAD FOR THE HIGHLY PARTISAN & HATEFUL DISTRICT ATTORNEY, THAT THE GRAND JURY IS SAYING, HOLD ON, WE ARE NOT A RUBBER STAMP.”

The grand jury voted to indict him the next day.

As Trump prepared to fly to New York the following week, rumors swirled that he was planning to turn his arraignment into a spectacle. One story claimed that his advisers were ready to use his mug shot for campaign merchandise; another reported that he wanted to be handcuffed behind his back as he walked into the courtroom. A confidant, noting that Easter was coming, urged him to lean into the Christ analogy.

Trump didn’t do any of it, opting instead to get in and out of New York as quickly and quietly as possible.

Politically speaking, the former president’s advisers may have been right. His campaign received millions of dollars in donations in the days after the indictment was announced. Arriving in Manhattan with dozens of supportive lawmakers in tow and holding a combative press conference in the gold‐plated lobby of his skyscraper would have been a show of strength. It could have reminded the world that he was still the front-runner for the Republican presidential nomination—and sent the message that Bragg hadn’t rattled him.

The problem was that the indictment had rattled him. For all his bluster, Trump desperately wanted to stave off an arrest, and he was embarrassed he hadn’t been able to. When it came time to turn himself in, he slipped out of Trump Tower and got into a black SUV.

Upon arrival at the courthouse, Trump was fingerprinted and processed, just like anybody else facing criminal charges in New York (though no mug shot was taken). Then he was escorted to the room where his lawyers were waiting. Across the hallway from this holding room were several empty jail cells.

“They stood up and saluted,” Trump told his lawyers when he returned from processing, according to a source who witnessed his comments. A week later, he’d tell the then–Fox News host Tucker Carlson that the court employees’ eyes were welling up as they processed him.

“They were actually crying,” he claimed. “They said, ‘I’m sorry.’ They said, ‘2024, sir, 2024.’ And tears were pouring down their eyes.”

The court employees at 100 Centre Street have seen it all. It’s a place packed with every kind of defendant—petty criminals, alleged killers, mobsters, celebrity defendants, and, yes, disgraced politicians. The staff aren’t known for saluting people as they take their fingerprints, and they certainly aren’t known for crying on the job. Shortly after the Carlson interview aired, “a law-enforcement source” familiar with the proceedings told the journalist Michael Isikoff of Yahoo News that Trump’s claims were “absolute BS.”

“There were zero people crying,” the source added. “There were zero people saying, ‘I’m sorry.’”

In their holding room at the courthouse, Trump and his lawyers were given copies of the 34‐count felony indictment that would soon be presented formally upstairs in the courtroom. Trump, however, took more interest in the placement of the television camera he would pass by on his way there. He knew the image of him walking by that camera would be played over and over again on television and social media. But the camera was way down the hallway—separated from the courthouse door by barricades—making it difficult, if not impossible, to be heard if he wanted to say anything. He wasn’t happy, but there was nothing Trump could do about it. This wasn’t his show. Still, he tried. For a few seconds when he was visible on camera, he managed to lock his gaze on the lens, glaring at the world as he walked by.

Inside the courtroom, Trump sat at the defendant’s table, flanked by his lawyers.

He had to wait a full five minutes before the judge came into the room. When the words “All rise!” rang out, everybody in the court, including Trump, had to stand.

D.A. Bragg and Juan Merchan, the presiding judge, were met by a version of Donald Trump that was much quieter, more somber—more timid—than the man he appeared to be on television and social media. The night before, he had said that Bragg should “INDICT HIMSELF.” But finally given a chance to confront them face‐to‐face, Trump was mostly silent. During the 57‐minute proceeding, Trump said just 10 words—“not guilty,” “yes,” “okay, thank you,” “yes,” “I do,” “yes”—and spoke so quietly that reporters had to strain to hear him.

For the first time in years, Donald Trump was not the most powerful person in the room.

As soon as the arraignment was over, Trump raced back to Mar-a-Lago, responding to his first indictment with a speech aimed squarely at the prosecutors closing in on him—not just Bragg, but also Fulton County D.A. Fani Willis, who is also Black (Trump called her the “local racist Democrat district attorney in Atlanta”), and the special counsel leading the Department of Justice’s investigations into January 6 and his handling of classified documents (a “lunatic special prosecutor named Jack Smith”). More than any potential Republican rival for the party’s presidential nomination—more than Biden, even—these were the people he was now running against.

“REPUBLICANS IN CONGRESS SHOULD DEFUND THE DOJ AND FBI UNTIL THEY COME TO THEIR SENSES,” he posted on Truth Social the following day. His campaign was selling T‐shirts (for $36) featuring a fake “mug shot” of Trump made to look as if it were a booking photo. Later in the week, his campaign posted a video advertisement featuring dramatic footage from Trump’s arraignment. Apparently, being indicted for paying off your porn‐star mistress was not something to be ashamed of in a Republican primary. “If they can do it to him they can do it to you,” Donald Trump Jr. tweeted. Noticeably absent from Trump’s obsession with his own victimization was any real focus on helping Americans who weren’t under criminal investigation, but his advisers were convinced that the ploy would work. “This week, Trump could lock down the nomination if he played his cards right,” Bannon told me as rumors began to swirl of Bragg’s indictment. “‘They’re crucifying me,’ you know, ‘I’m a martyr.’ All that. You get everybody so riled up that they just say, ‘Fuck it. I hate Trump, but we’ve got to stand up against this.’”

The trial date for the hush‐money case was later set during a hearing with Judge Merchan where Trump appeared via video from a room in Mar‐a‐Lago. For most of the appearance, Trump silently listened, his microphone on mute. But when the judge announced the court date—March 25, 2024—he reacted angrily, waving his hands and shaking his head. No one in the courtroom could hear him, but he appeared to be yelling at the lawyer sitting next to him in Mar-a-Lago, Todd Blanche. According to a source there with Trump, the former president erupted at Blanche because the March 2024 trial would be during a crucial point in the presidential campaign.

“That’s in the middle of the primaries!” Trump yelled. “If I lose the presidency, you are going to be the reason!”

Trump’s tantrum, according to the source, continued for nearly 30 minutes after the court appearance ended and the camera was turned off—a withering attack on perhaps the most highly regarded lawyer on Trump’s troubled legal team.

“You little fucker!” Trump yelled at Blanche. “You are going to cost me the presidency!”

(A spokesperson for the Trump campaign disputed that the former president was angry with his lawyer about the trial date or accused him of jeopardizing his presidential campaign, saying, “President Trump and Mr. Blanche are united in fighting these unlawful witch-hunts and the weaponization of the justice system.”)

About a month before his first indictment, Trump was about 10 miles south of the White House, addressing attendees at the Conservative Political Action Conference at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center, in Maryland. CPAC this year looked like a full‐blown Trump convention. Devotees of the former president such as Representatives Matt Gaetz and Marjorie Taylor Greene were among the warmest-received by the crowd.

Trump had the keynote time slot on Saturday night. After the public‐address system introduced him as the “next president of the United States,” he ambled onto the stage and spoke for nearly two hours.

“The sinister forces trying to kill America have done everything they can to stop me, to silence you, and to turn this nation into a socialist dumping ground for criminals, junkies, Marxists, thugs, radicals, and dangerous refugees that no other country wants,” he said. The speech was ominous, but one rhetorical flourish stood out. “In 2016, I declared I am your voice. Today, I add: I am your warrior; I am your justice,” Trump said. “And for those who have been wronged and betrayed, I am your retribution.” He repeated the last phrase—“I am your retribution”—and promptly the crowd started chanting: “U.S.A.! U.S.A.! U.S.A.!”

When I spoke with Bannon a few days later, he wouldn’t stop touting Trump’s performance, referring to it as his “Come Retribution” speech. What I didn’t realize was that “Come Retribution,” according to some Civil War historians, served as the code words for the Confederate Secret Service’s plot to take hostage—and eventually assassinate—President Abraham Lincoln.

“The use of the key phrase ‘Come Retribution’ suggests that the Confederate government had made a bitter decision to repay some of the misery that had been inflicted on the South,” William A. Tidwell, James O. Hall, and David Winfred Gaddy wrote in the 1988 book Come Retribution: The Confederate Secret Service and the Assassination of Lincoln. “Bitterness may well have been directed toward persons held to be particularly responsible for that misery, and Abraham Lincoln certainly headed the list.”

Bannon actually recommended that I read that book, erasing any doubt that he was intentionally using the Confederate code words to describe Trump’s speech.

Trump’s speech was not an overt call for the assassination of his political opponents, but it did advocate their destruction by other means. Success “is within our reach, but only if we have the courage to complete the job, gut the deep state, reclaim our democracy, and banish the tyrants and Marxists into political exile forever,” Trump said. “This is the turning point.”

The “Come Retribution” speech was a turning point for Trump’s campaign. The trial date for the charge of interfering in the 2020 election has been set for March 4; for the hush-money case, it’s March 25; for the classified-documents case, it’s May 20. As Election Day approaches and he faces down these many days in court, he will be waging a campaign of vengeance and martyrdom. He will continue to talk about what is at stake in the election in apocalyptic terms—“the final battle”—knowing how high the stakes are for him personally. He can win and retake the White House. Or he can lose and go to prison.

“Trump’s on offense and talking about real things,” Bannon told me. “The ‘Come Retribution’ speech had 10 or 12 major policies.” But Bannon knew that the speech wasn’t about policies in a traditional sense. Trump spoke about whom he would target once he returned to power. “We will demolish the deep state. We will expel the warmongers,” Trump said. “We will drive out the globalists; we will cast out the communists. We will throw off the political class that hates our country … We will beat the Democrats. We will rout the fake news media. We will expose and appropriately deal with the RINOs. We will evict Joe Biden from the White House. And we will liberate America from these villains and scoundrels once and for all.”

A couple of days after Special Counsel Jack Smith finally indicted him for his actions leading up to January 6, Trump made his threat explicit: “IF YOU GO AFTER ME, I’M COMING AFTER YOU!”

That, more than anything else, is the beating heart of Trump’s 2024 campaign: Vote for me, and I will punish the people who have wronged you—by wronging me. I am your retribution.

This essay is adapted from the forthcoming Tired of Winning: Donald Trump and the End of the Grand Old Party.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.