What to Read, Watch, and Listen to Today

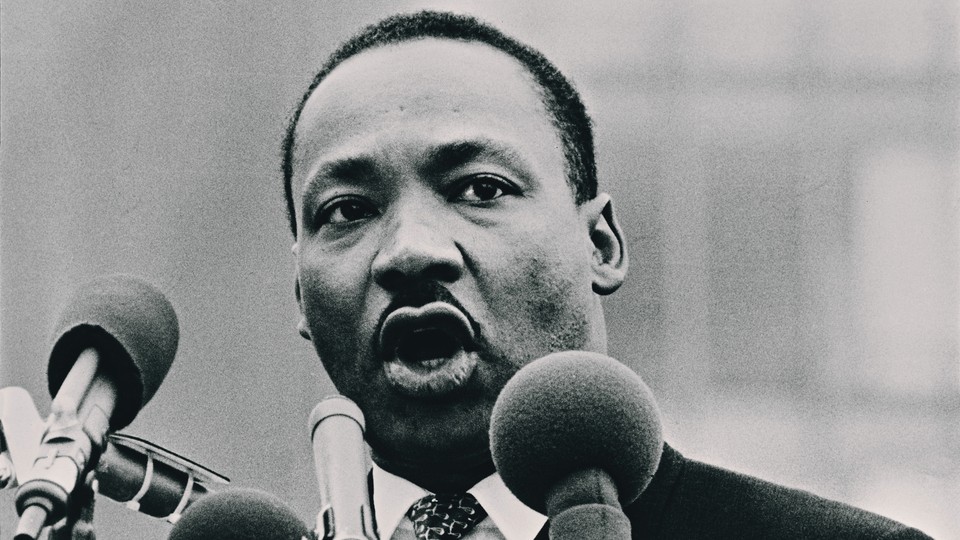

Suggestions for your downtime this Martin Luther King Jr. Day

This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

In an era when many of the civil-rights policies enacted in the 1960s face serious threats, I expect there will be a renewed urgency and vigor to the annual goings-on this Martin Luther King Jr. Day. Below are some suggestions for how to use your downtime today.

First, here are three new stories from The Atlantic:

Today marks the 39th year that Martin Luther King Jr. Day has been celebrated nationally. King Day is one of those things that feels like it’s been around everywhere forever, but the federal holiday has only been recognized in every state since 2000—and, regrettably, two of those states, Alabama and Mississippi, still choose to celebrate the Confederate general Robert E. Lee alongside King, ostensibly because their birthdays are close to each other. (So far, my requests that they also consider celebrating fellow noted Capricorns Sade Adu and Ray J have gone unanswered.)

The changing meaning of Martin Luther King Jr. Day over the years is a useful barometer for the ongoing discourse on race in America. The King Day of my childhood had already been Easy-Baked into a holiday of half-hearted days of service and sappy television specials; my teachers would roll out the big TV to play Roots or Eyes on the Prize on LaserDisc. But the idea of a federal holiday to celebrate King was once fiercely contested. The late Senator John McCain voted against the original federal bill in 1983, and in 1987, the incoming governor in his home state of Arizona, Republican Evan Mecham, killed a plan to begin observing the holiday. It took five more years—and the NFL moving a Super Bowl away from the state in protest—before a referendum finally approved the measure. For years, millions of Americans were so wary of putting King on a pedestal hitherto reserved for George Washington and Christopher Columbus that they actively opposed a paid Monday off. That’s serious commitment.

Befitting all of the blood, sweat, and tears that went into the holiday’s creation, the first Martin Luther King Jr. Day, in 1986, was a big deal. As Time reported in 2017, the first observance—just two decades after the end of the civil-rights movement—was one of nationwide mass marches, candlelight vigils, and even a freedom train in California. Now, following the death of affirmative action at the hands of the Supreme Court, in an era when many of the civil-rights policies enacted in the 1960s face serious threats, I expect there will be a renewed urgency and vigor to the annual goings-on.

What’s the best way to celebrate the firefighter when the house is still burning? I’ve got a few pitches for your downtime. The Atlantic’s KING issue, released in 2018, 50 years after King’s assassination, features a wealth of speeches from King that you might not have seen, as well as essays from prominent scholars and thinkers that contemplate King’s philosophy and life. As something of a follow-up to that special issue, last winter, I helped create the podcast Holy Week, which tells the story of the week after King’s assassination—and how the most widespread unrest in America in 100 years coincided with the country’s retreat from King’s agenda.

If you can’t find the old LaserDiscs, I might suggest streaming Lowndes County and the Road to Black Power, which chronicles the fight to organize rural Black Alabamians that began immediately after the famous Selma to Montgomery marches, in 1965. It’s also not a bad time to crack open Jonathan Eig’s 2023 best-selling biography, King: A Life, or the historian Michael K. Honey’s Going Down Jericho Road, a brilliant history of the Memphis Sanitation Workers’ Strike and King’s last days.

There also might not be a better time for turning to public spaces to learn about King and the story of Black folks in America. Atlanta houses the King Center and several historic sites related to King’s life. The National Civil Rights Museum, converted from Memphis’s Lorraine Motel, where King was assassinated, still maintains the room where he was killed, exactly as it was on April 4. In Washington, D.C., the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, the Anacostia Community Museum, and the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library all offer great resources for adults and children alike. There’s a new International African American Museum in Charleston, South Carolina, and the DuSable Black History Museum, in Chicago, is hosting a day of service. Take in the history now, before it’s gone.

Related:

Today’s Read

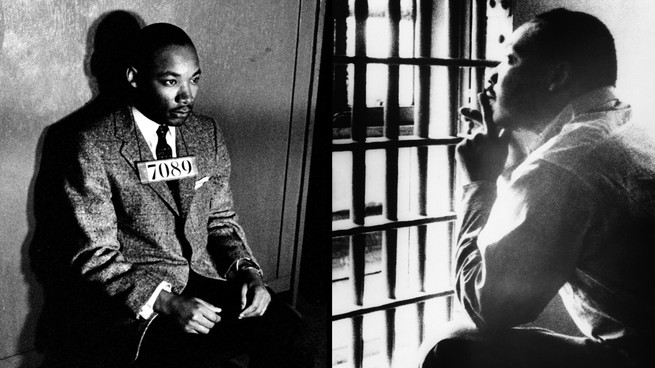

Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter From Birmingham Jail”

By Martin Luther King Jr.

My Dear Fellow Clergymen:

While confined here in the Birmingham city jail, I came across your recent statement calling my present activities “unwise and untimely.” Seldom do I pause to answer criticism of my work and ideas. If I sought to answer all the criticisms that cross my desk, my secretaries would have little time for anything other than such correspondence in the course of the day, and I would have no time for constructive work. But since I feel that you are men of genuine good will and that your criticisms are sincerely set forth, I want to try to answer your statement in what I hope will be patient and reasonable terms.

I think I should indicate why I am here in Birmingham, since you have been influenced by the view which argues against “outsiders coming in” … Several months ago the affiliate here in Birmingham asked us to be on call to engage in a nonviolent direct-action program if such were deemed necessary. We readily consented, and when the hour came we lived up to our promise. So I, along with several members of my staff, am here because I was invited here. I am here because I have organizational ties here.

But more basically, I am in Birmingham because injustice is here.

More From The Atlantic

Culture Break

Read. Octavia Butler, the author of unnervingly predictive fiction, forecast America’s slide into autocracy. We need her insight more than ever, Tiya Miles writes.

Watch. True Detective: Night Country marks the return of an acclaimed anthology series that’s charting new territory, Jeremy Gordon writes.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.