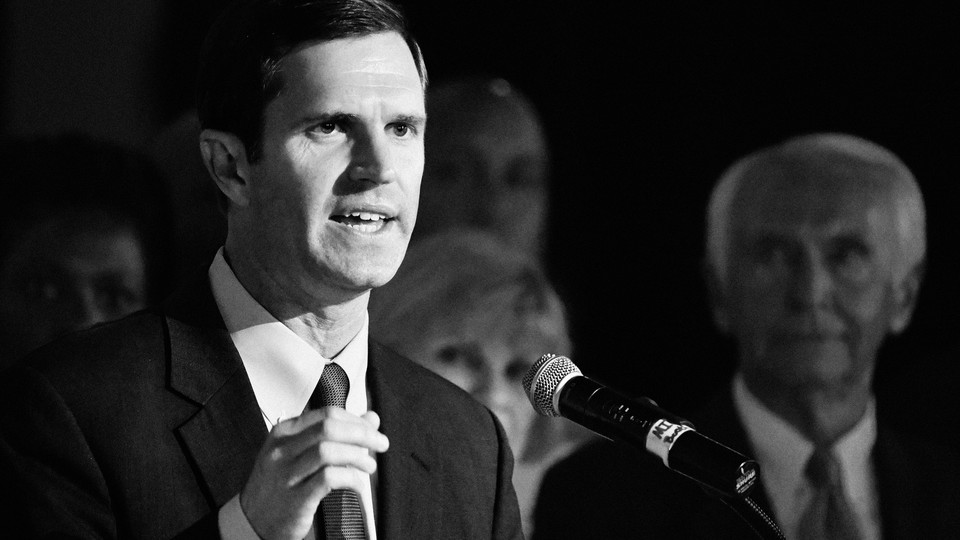

Why Deep-Red Kentucky Reelected Its Democratic Governor

Andy Beshear’s victory allows his party to maintain one of its most surprising footholds in the South.

Updated at 8:58 p.m. ET on November 7, 2023

The GOP controls nearly everything in Kentucky, a state that Donald Trump carried by 26 points in 2020. Republicans hold both U.S. Senate seats and five of Kentucky’s six House seats; they dominate both chambers of the state legislature.

What Republicans don’t occupy—and won’t for the next four years—is Kentucky’s most powerful post. The state’s governor is Andy Beshear, a Democrat elected in 2019 who won a second term tonight. Beshear defeated Daniel Cameron, the state’s 37-year-old Republican attorney general, allowing Democrats to maintain one of their most surprising footholds in southern politics.

Beshear, 45, owes his success in a deep-red state to a combination of competent governance, political good fortune, and family lineage. His father, Steve, was a popular two-term governor who governed as a moderate and won the admiration of fellow Democrats for implementing the Affordable Care Act in the face of conservative opposition. The Republican governor whom Andy Beshear defeated in 2019, Matt Bevin, was widely disliked, even by many in his own party. Soon after taking office, Beshear earned praise for his steady leadership during the coronavirus pandemic and then later in his tenure during a series of natural catastrophes—deadly tornadoes, historic flooding, and ice storms. The crises have made the governor a near-constant presence on local news in the state, where allies and opponents alike usually refer to him by his first name. “I joke that Andy Beshear has 150 percent name ID” in Kentucky, Representative Morgan McGarvey, the lone Democrat in the state’s congressional delegation, told me. “It’s because everybody knows who he is. And they actually know him.”

Major economic-development and infrastructure projects also boosted the governor’s reelection bid—Beshear took advantage of billions in federal dollars that have flowed to Kentucky from legislation signed by President Joe Biden and backed by the state’s most powerful Republican, Senator Mitch McConnell.

Cameron is a onetime McConnell protégé who would have been the state’s first Black governor if elected. In the campaign’s closing weeks, Cameron touted an endorsement by Trump and tried to tie Beshear to Biden, who is deeply unpopular in Kentucky. The governor endorsed Biden’s reelection, though he’s generally kept his distance from the president. At the start of one debate, Beshear, who had recently signed legislation legalizing sports gambling, “wagered” that Cameron would mention Biden’s name at least 16 times in their hour together onstage. Cameron was either unfazed or unable to improvise: He mentioned Biden’s name four times in the next 90 seconds.

Nationalizing the governor’s race was probably Cameron’s smartest bet in a state like Kentucky. But even Republicans conceded that Beshear had done a good job of building a distinct brand during the past four years. “He ended up being able to operate in some nonideological arenas—the tornadoes, the floods, even COVID while it was going on,” Scott Jennings, a Republican consultant in Kentucky, told me. As they did for governors in most states, televised briefings during the pandemic allowed Beshear to connect with his constituents on a daily basis for weeks. The dynamic generally helped Republican leaders in blue states, such as Phil Scott in Vermont, and vice versa in Kentucky. “Anytime you come into people’s lives like that every day during an unusual situation, it does have an impact,” Jennings said. “You seem more familiar than the average politician that you see every now and again.” Since the beginning of 2020, just one governor—Democrat Steve Sisolak in Nevada—has lost a reelection bid.

Beshear benefited from incumbency in other ways as well. He raised and spent far more money than Cameron, which allowed him to blanket the state in ads both positive and negative. He used ribbon cuttings and groundbreakings to tout job-creating projects. In September, Beshear placed the state’s first legal sports bet at the Churchill Downs Racetrack, a launch that was timed explicitly for the start of football season and implicitly for the start of his reelection campaign.

Among the issues Beshear prioritized was abortion, a departure for a Democrat in a culturally conservative southern state. The procedure has been illegal in Kentucky since the overturning of Roe v. Wade triggered a statewide ban. But Democrats sensed a political opening last year after Kentucky voters rejected an amendment that would have stipulated that the state constitution did not protect abortion rights. The vote suggested that in Kentucky, as in other red states, such as Kansas, abortion rights have bipartisan support. “It’s a huge advantage for Andy,” former Representative John Yarmuth, a Democrat who served for eight terms in the House before retiring last year, told me. “It has become a voting issue for the pro-choice side. It generates turnout and it moves some voters.”

One of Beshear’s TV ads featured a woman who was raped by her stepfather at age 12 and who criticized Cameron for his support of Kentucky’s abortion ban, which contains no exceptions for rape or incest. “I’m speaking out because women and girls need to have options. Daniel Cameron would give us none,” the woman says. After the ad began running, Cameron said that if the legislature presented him with a bill adding exceptions to the state’s abortion ban, he would sign it.

For Cameron, the Republican who had the best chance of winning him votes was Trump. The former president released a recorded endorsement last week, but he did not come to Kentucky to campaign for the attorney general. “We would accept any and all visitors to help get the vote out,” Sean Southard, a spokesperson for Cameron, told me when I asked whether the campaign had wanted a Trump rally. Trump held a “tele-rally” for Cameron on the eve of Tuesday’s vote, but he never stepped foot in Kentucky during the campaign.

What role, if any, race might have played in the outcome was also a question mark. Cameron denounced a pair of ads by the Beshear-backing Black Voters Matter Action PAC that refer to him as “Uncle Daniel Cameron” and place his image alongside that of Samuel L. Jackson’s character from Django Unchained. “All skinfolk ain’t kinfolk,” a narrator said in a radio ad, urging a vote for Beshear, who is white.

Republicans have tended to see Beshear as something of an accidental governor. After winning his race for attorney general in 2015 by slightly more than 2,000 votes, he defeated Bevin four years later by a margin nearly as minuscule (about 5,000 votes). The GOP-controlled legislature drives policy and can override his veto with a simple majority. “The Republican supermajorities have essentially stuffed him in a locker,” Jennings said. But, he argued, their dominance ultimately helps Beshear politically because they’ve prevented him from building a record to the left of where Kentucky voters want to go. “If left to his own devices, he’d be far more liberal on policy,” Jennings said. “In some ways, they save him from himself.”

As entrenched as they are in Kentucky’s legislature and congressional delegation, Republicans have struggled to win, and keep, the governorship. They’ve held the top job for just three four-year terms in the past eight decades, and both of their recent winners, Bevin and Ernie Fletcher, lost bids for reelection (each time to a Beshear). “What’s clear is that people view the governor differently,” McGarvey told me.

Both Republicans and Democrats I spoke with told me that they believed the GOP’s strength throughout the state would eventually extend to the governor’s office. But with a Beshear on the statewide ballot for the sixth time in the past two decades, Democrats were able to hold on at least once more. Private polls had showed Beshear with a small but not insurmountable lead, according to operatives in both parties who described them on the condition of anonymity. Public surveys have been limited, but they showed a tightening race as well. Democrats close to the Beshear campaign told me that although they felt good about the race, a Cameron victory would not have surprised them given the GOP’s overall advantage. As the votes were tallied tonight, however, Beshear was improving on his 2019 performance in counties big and small.

The results did not surprise Yarmuth. Sensing a lack of enthusiasm on the Republican side, Yarmuth had been confident of a Beshear victory and had even held out hope for a win large enough to help Democrats in down-ballot races. But he, too, was skeptical that Democrats would be able to maintain their unlikely grip on Kentucky’s governorship much longer. “I would bet,” the former representative told me, “that it’ll be hard for a Democrat past Andy.”