Why Elite-College Admissions Matter

A conversation with Annie Lowrey about how to diversify these schools—and by extension, America’s elite

This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

Attendance at an elite college increases a student’s chances of joining America’s most elite ranks, according to a new study. I chatted with my colleague Annie Lowrey, who reported on this new research yesterday, about how to diversify the student bodies of America’s wealthiest schools—and, by extension, the whole of elite America.

First, here are three new stories from The Atlantic:

A Propulsive Quality

A new study by a group of economists found what might seem to be an obvious correlation: Attending an elite school ups a person’s chances of ascending the ranks of elite society. The study, conducted by Raj Chetty of Harvard, David Deming of Harvard, and John Friedman of Brown University, looked at waitlisted students’ outcomes and showed that compared with attending one of America’s best public colleges, attending a member of what’s known as the “Ivy Plus” group—the Ivies plus Stanford, MIT, Duke, and the University of Chicago—increases a student’s chances of reaching the top of the earnings distribution at age 33 by 60 percent.

The finding is not actually so obvious. Over the past two decades, a body of research has shown that students’ average incomes end up about the same after they graduate from a flagship public institution versus an Ivy Plus school. The new study confirms this finding about average incomes, but it complicates the bigger picture: When it comes to other metrics of life in the American elite—“Supreme Court clerkships, going to a tippy-top graduate program, making it into the top 1 percent of earners at the age of 33”—schools such as Harvard and Yale matter a lot. “In general, [elite schools have] this propulsive quality,” Annie told me.

White students and, to an even greater extent, wealthy students are overrepresented at many elite colleges, and the question of how these schools can diversify has become even more urgent since the Supreme Court’s decision to curtail affirmative action. But this new study suggests that elite schools can enact some straightforward policies to diversify themselves and, in the process, the makeup of elite America. Annie and I talked through two of these possibilities.

Disbanding legacy admissions: Systems that give preference to the children of university alumni have come under scrutiny in recent years, and this scrutiny has intensified since last month’s Supreme Court ruling. Today, the Education Department said it has opened a civil-rights investigation into Harvard’s legacy-admissions practices. And last week, Wesleyan University (my own alma mater) declared an end to its use of legacy preferences.

The new paper from Chetty and his co-authors confirms that the effects of legacy admissions are real, and that they’re particularly strong for the highest-income students. The data show that legacy students whose parents are in the top 1 percent of the earnings distribution are 5 times more likely to be admitted to an Ivy Plus school compared with non-legacy students with equivalent test scores. Meanwhile, less wealthy legacy students are 3 times more likely to be admitted.

When I asked Annie if she thought the decline of legacy admissions at elite schools is a real possibility (MIT is the only school out of the Ivy Plus group studied that doesn’t use legacy preferences), she noted that this is quickly becoming a public-policy issue: President Joe Biden came out against the practice after the Supreme Court ruling, and according to polling, about three-quarters of Americans think colleges shouldn’t use legacy preferences. Universities might start to rethink their use of the practice if their presidents start getting asked about it over and over again, Annie said, “and if you start to have members of Congress saying, ‘Do we need to be giving these institutions all of this research funding and all of these nice tax breaks if they’re just picking rich kids and giving them more advantage?’”

President Biden is a particularly interesting political figure for this moment: As Annie reminded me, Biden was purportedly not a very good student, and he did not attend an elite college, as many past presidents did (he went to the University of Delaware). Meanwhile, many members of Congress come from elite colleges themselves, Annie noted: “The thing that will be most interesting is if this becomes political, and for whom does it become political?”

Increasing class sizes: I asked Annie to elaborate on a surprisingly simple argument she makes at the end of her article, one that isn’t explicitly covered in the Chetty research: Elite schools might just matriculate more students. “These schools have not grown with the growth of the United States population or the population of 18-year-olds,” she told me. We pulled up the statistics together over the phone: These Ivy Plus schools graduate about 23,000 students a year combined. Meanwhile, there are about 4 million 18-year-olds in America in any given year. Of course, not all of those kids are going to go to college. But 23,000 is “a drop in the bucket,” Annie said.

These schools have tremendous financial resources—a combined endowment of more than $200 billion for those Ivy Plus schools. Moreover, many of these schools spend lavishly on what are essentially “real-estate concerns,” such as sports facilities and dining halls, Annie said: “The notion that they couldn’t be educating many, many, many more kids is risible.”

Related:

Today’s News

- The International Brotherhood of Teamsters has called off a nationwide strike threat after securing a tentative five-year agreement with UPS leadership.

- Qin Gang was ousted from his role as China’s foreign minister after a month-long absence from public view. His predecessor will replace him.

- A federal judge struck down the Biden administration’s new asylum policy, which has reduced illegal crossings on the southern border.

Evening Read

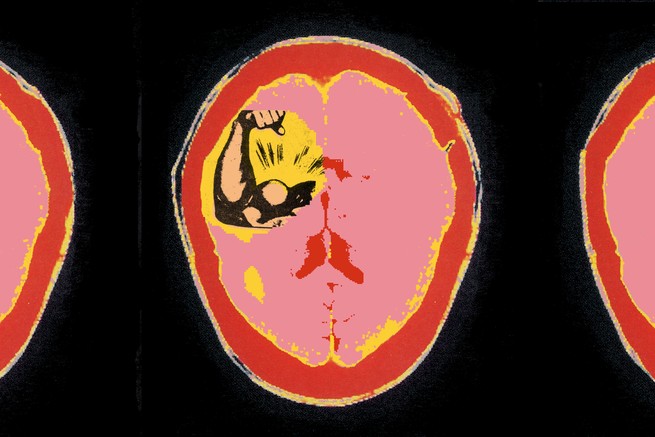

Power Causes Brain Damage

By Jerry Useem (From 2017)

If power were a prescription drug, it would come with a long list of known side effects. It can intoxicate. It can corrupt. It can even make Henry Kissinger believe that he’s sexually magnetic. But can it cause brain damage?

When various lawmakers lit into John Stumpf at a congressional hearing last fall, each seemed to find a fresh way to flay the now-former CEO of Wells Fargo for failing to stop some 5,000 employees from setting up phony accounts for customers. But it was Stumpf’s performance that stood out. Here was a man who had risen to the top of the world’s most valuable bank, yet he seemed utterly unable to read a room.

More From The Atlantic

Culture Break

Read. These seven books for the lifelong learner may tempt you to take up a new pursuit.

Listen. Tony Bennett, who died on Friday, reportedly sang one last song while sitting at his piano. It’s also the one that made him a star.

Katherine Hu contributed to this newsletter.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.