You’ve Never Seen a Star Like This

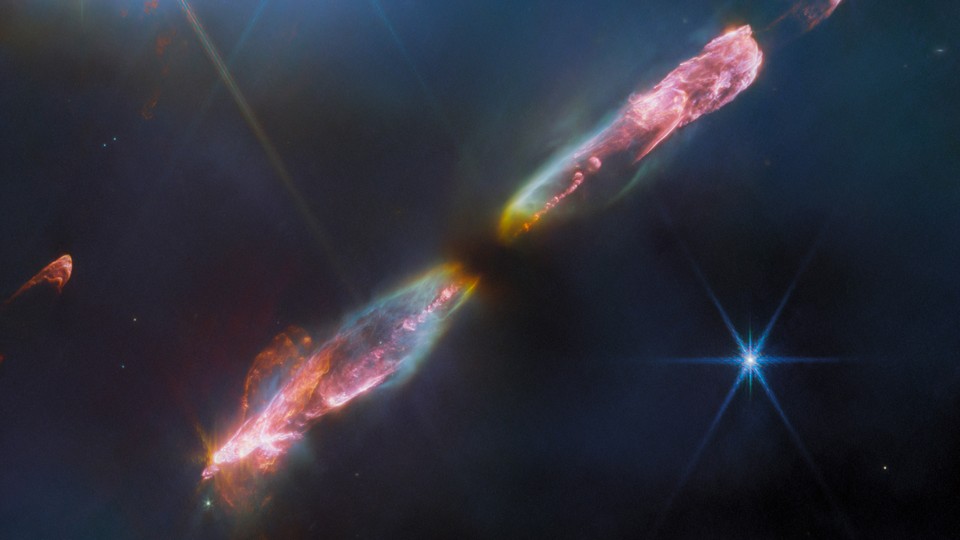

A new image from the Webb telescope shows an infant star not as a diamond hanging in the sky, but as a velvety, dark orb surrounded by jets of radiant dust.

From our perspective down here, on the surface of our planet, the stars are tiny, gleaming specks in an inky-dark universe. Occasionally they appear to twinkle, when the air in our atmosphere bends the incoming light. Through telescopes, they are balls of light, their glow distorted by the lens. And up close, the best star in the universe—our sun—is an orangey sphere of flame.

But stars can be so much more than that, as telescopes, especially the very good ones, can reveal. The James Webb Space Telescope—the most powerful space observatory ever built, perched a million miles from Earth—has captured a portrait of a star about 1,000 light-years away. It’s not a diamond hanging in the sky, but a velvety, dark orb, suspended in space, with jets of bright material unfurling on two sides like the long, shimmery wings of an insect. Stars twinkle, yes. But they can also illuminate the darkness in ways utterly unlike anything we’re used to.

The star in the image is a newborn in stellar terms, also called a protostar. Stars have life spans of their own—they are young, they grow up, they grow old. When they are infants, freshly ignited from clumps of cold gas and dust that have collapsed under their own gravity, they can absorb the leftover material from their formation and eject some of it in a pair of narrow jets. The gush smashes into the surrounding interstellar gas and dust, and the constant collisions produce those radiant wings.

The new picture is a result of the Webb telescope’s capacity to study the universe in, quite literally, a new light. In the beginning, protostars are encased in the dusty molecular cloud of their formation, a cocoon that most visible light can’t pierce. If you looked at the baby star with the naked eye—or even a different kind of telescope—you’d just see a sparkly, opaque cloud of stardust. But Webb is specifically designed to detect infrared light, which is invisible to the human eye but can pass through such dust. By absorbing the infrared light emitted from the excited molecules within the outflows, the Webb telescope was able to capture their structure in mesmerizing detail.

Astronomers have observed the outflows of protostars before, and they have a good understanding of the swirling chaos. But to witness it with such richness and texture is another experience; it scrambles our familiar understanding of what stars—those beautiful pinpricks that follow us around at night—can be. The newest image reminds me of Webb’s observations of Neptune and Uranus, which looked so different from previous pictures; suddenly, the outer planets were not dull gray and blue, but incandescent, each with a set of beautiful rings.

The strange-looking star recorded by Webb is a vision of our cosmic past: This is very likely what our sun looked like when it was just a few tens of thousands of years old, with only 8 percent of the mass it has today. Our sun is now about 4.6 billion years old, and it will remain its usual, shining self for another 5 billion years or so, no giant pair of jetstreams to be found. This distant object will eventually become a sunlike star, or even two; certain wiggles in the outflows suggest the presence of a pair of baby stars, according to NASA and the European Space Agency. Many stars exist in this arrangement, as binary pairs, gravitationally bound to each other. Some stars even come in triples; the nearest star system to us, about 4.3 light-years away, consists of a trio of stars, orbiting together—two sunlike stars, and one dimmer, cooler one.

We can’t predict what kind of system will take shape around this newborn star (or stars), but there might be enough cosmic bits and pieces left over to form planets. Maybe this spot in the universe will someday spark a simple form of life into being, and nourish it for eons, the way it happened here, long enough for a few of its inhabitants to invent nearly magical tools to explore the depths. Perhaps the effort will prompt them to rethink the cosmos, in the way we are now.